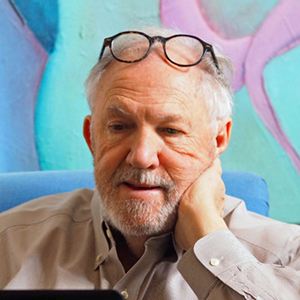

In Memoriam: Larry McMurtry (1936-2021)

On the first hour of the first day of my first college course—the mandatory English literature— a rookie instructor teaching the first class of his first day as a lecturer ambled into the TCU classroom only a few minutes tardy. It was the fall of 1961, an 8 a.m. class. He was a trifle late because, like the freshmen seeking higher education enlightenment, his campus navigation skills lacked honing.

He squinted at the class through glasses, walked to the front side of the desk, slid his posterior into reverse and then, comfortably centered and seated atop the desk, crossed his legs as if anointing himself a literary Buddha.

“I’m Larry McMurtry,” he said. “As you know, I am an author.”

Fresh student O.K. Carter’s first thought: “What a nimrod.” First impressions often lack accuracy. How could I know the innocuous man in front of me would eventually win a Pulitzer Prize for fiction? And an Academy Award for screen writing. That he would author more than 30 books, most of them best sellers, and more than 30 screenplays, the resulting movies winning numerous Academy Awards themselves in an assortment of categories. A future legend-to-be right in front of me.

McMurtry, 84, died in March in his hometown of Archer City.

Back then, in 1961, he showed up as a young man with a newly inked master’s degree from Rice. He clearly believed the registration catalog contained his name, which should have been sufficient for literary-aware students to look him up. He had, afer all, just been named the recipient of a Best First Novel by a Texas Writer award (for years he was tagged as a “minor regional novelist”). Trouble was, the registration catalog contained a full page of English 101 classes. Most of the classes would be taught by someone namelessly anonymous called “Staff.” Including McMurtry. Worse, the university shuffled registration alphabetically every semester, in this semester those students with surnames beginning with A-B-C-D signing up dead last. The only class the late registrants could get was the dreaded Monday-Wednesday-Friday 8 a.m. Larry McMurtry. To us, just another of the nameless Staff.

That first day he wore a wrinkled white sport coat blazer that seemed identical to one I owned, and which might have been. I bought mine in a Wichita Falls department store, not far from where McMurtry grew up.

“You’ll see a lot of this sports coat,” he said. “It’s the only one I own.” The coat did show up frequently in tandem with what evolved as his lifeMme uniform: blue jeans, blue Oxford button down shirt.

His speech pattern sounded peculiar, slow and more Southern than Texan. With a trace of what I believed must have been an almost-corrected childhood lisp. Rarely showing up with lecture notes, he talked about Hemingway and Dobie, Salinger and Webb, Faulkner, and Bedichek, and a host of unfamiliar screenwriters. He was not my mentor—he was never particularly close to students or fond of teaching—but at the same time he was not that much older than me. We played a bit of pool and ping pong afer classes on occasion, the recreation facility being in the same building. He usually won at table tennis, lost at pool. Some class members, myself included, went with him to the New Isis in north Fort Worth, not to see the movie but to dissect the screenplay, a new way of looking at literature. He gave us lists of rare books he wanted, asking us to scout book sales. He’d financed his way through college collecting and selling books, a habit he continued his whole life.

Somewhere in the middle of that first semester it became evident, in a gradual attitudinal shift, that I was in the presence of something special. Something extraordinary. I signed up for the second semester, searching through the list of staff in the registration catalog until I found the name I wanted: McMurtry, Larry. That second semester, his first novel, Horseman Pass By, was purchased by the movies, coming out as Hud. The book’s demythologization of the American West, both historic and modern day, remained a lifelong theme. Hud was nominated for seven Academy Awards winning three. McMurtry was on his way and out of teaching by the end of that semester. The Last Picture Show, Leaving Cheyenne, Cadillac Jack, Somebody’s Darling, Desert Rose, Terms of Endearment and others followed. His co-written screenplay Brokeback Mountain won an Academy Award. Movies stemming from his books were nominated for 34 Oscars, winning 13.

Though his literary focus was different, McMurtry was, in my opinionated view, what Hemingway could have been but was not.

The Metroplex was not McMurtry’s turf, but Arlington did not escape his attention. One of his fictional characters, Danny Deck, ended up in the grips of a migraine and stayed overnight. The Deck character described Arlington as “a vast labyrinth of cul-de-sacs surrounding a giant amusement park. Once in, only a native can find their way back out.”

It’s an annoying (and untrue) passage that reappears every time the topic of mass transportation in Arlington comes up.

One day I read Lonesome Dove, just released, a book that began as a hundred-page screenplay (the stars were to be John Wayne, Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart), and which, the film not being made, morphed into an astonishing book. I took it to one of the Star-Telegram’s more literary-inclined members, telling him Lonesome Dove was going to be monumental.

He scoffed. “It’s a Western,” he said.

“Lonesome Dove will be to the Western as Gone with the Wind is to the South,” I predicted (It’s good to be right about something now and then).

He laughed and handed the book back. It was with considerable pleasure someMme later that I dropped an A.P. story on the friend’s desk, announcing the Pulitzer Prize in fiction: Lonesome Dove.

Did McMurtry and I stay in touch, the master giving me writing tips? Regretfully, no. His confidantes and writing associates tended to be women. After college I ran into McMurtry only three times, all at assorted literary events. At one of those in Fort Worth he signed my copy of his latest book. He showed no recognition whatsoever, not at my face, not at my name. Not an issue. In time I taught college classes myself, and most assuredly there are many freshmen former students I will never recognize and who I would prefer to forget.

“You’ve done well,” I told him when he autographed and returned my copy of the book.

“Thanks,” he said, looking behind me at the line of people with books to sign. “Next!”