The Snively Expedition - Its Progress

Excerpt from History of Texas: From Its First Settlement in 1685 to Its Annexation to the United States in 1846, Volume 2 by H. Yoakum, Esq.

In 1842, information was transmitted to Texas, through a gentleman in Missouri, that a rich caravan of Mexicans, having a large number of mules and a hundred and fifty thousand dollars in specie, had passed from Santa Fé to Independence, and would thence proceed to the eastern cities to convert their specie into merchandise, setting out on their return to Santa Fe in the spring of 1813. As they would on the route pass through the territory of Texas, many of the Texans were desirous to capture them. Accordingly, on the 28th of January, 1843, Colonel Jacob Snively made application to the Texan government for authority to raise men to proceed to the northern portion of the republic, and capture the caravan. On the 16th of February, the permission was granted by the war department, and he was authorized to organize such force, not exceeding three hundred men. The expedition was to be strictly partisan, the troops to mount, arm, equip, and provision themselves, and to have half the spoil—but this was to be taken only in honorable warfare. They were authorized to operate above the line of settlements between the Rio del Norte and the United States boundary, but were to be careful not to infringe upon the territory of that government.* Such were Colonel Snively's instructions, and such his authority.*G. W. Hill, Secretary of War, to Jacob Snively, February 16, 1843.

The troops rendezvoused at Georgetown, six miles from Coffee's station, and the then extreme frontier. On the 24th of April, a sufficient force having arrived, the orders of the secretary of war were exhibited. Colonel Snively was unanimously chosen to the command; but so much of the order of the war department as provided that one half of the spoil should be paid over to the government "was unanimously rejected by vote."† The volunteers adopted a set of by-laws, and decided that the army regulations should govern them, when not in conflict with the by-laws.†I quote from the admirable manuscript journal of the expedition furnished me by Colonel Stewart A. Miller.

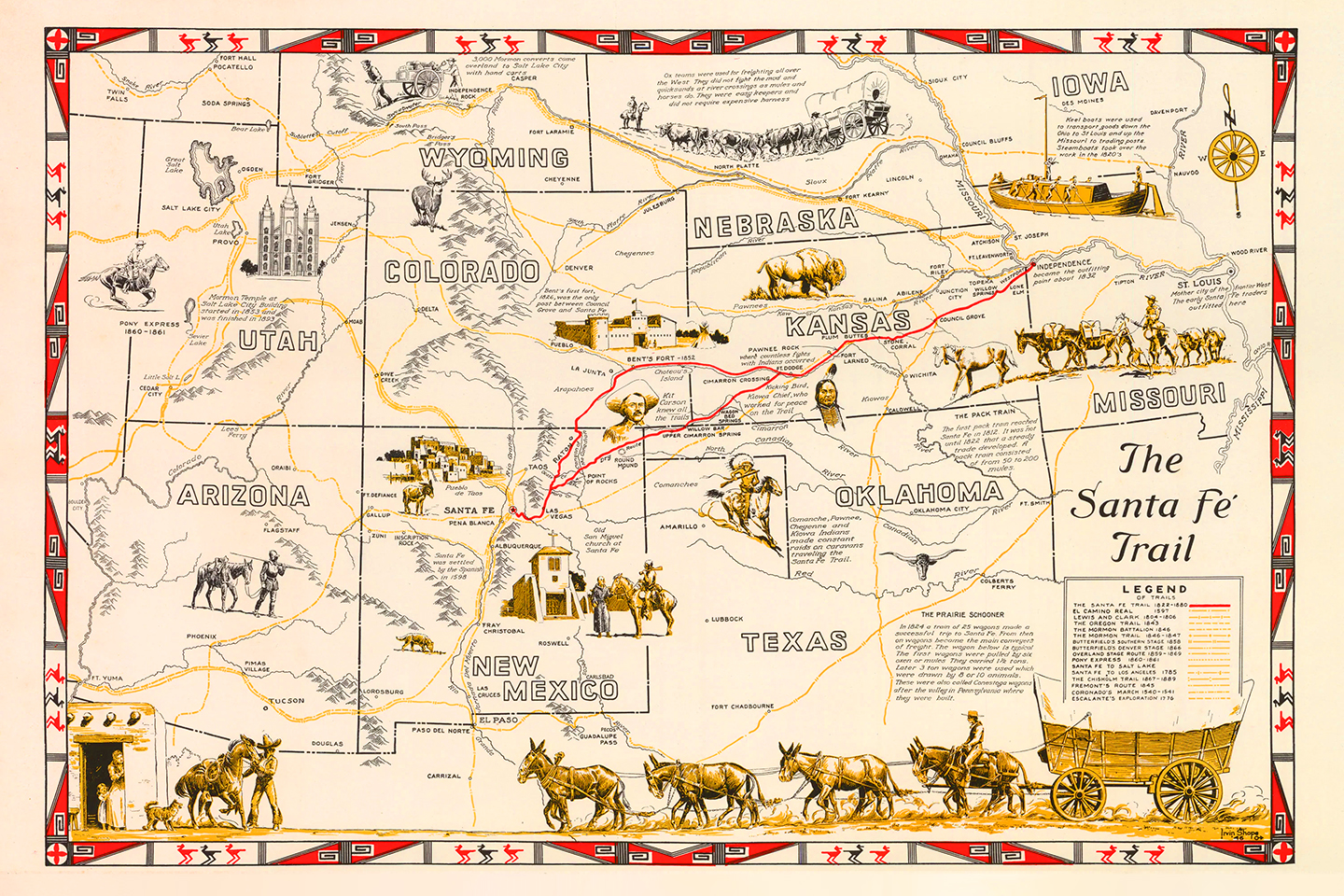

On the 25th of April, having about one hundred and seventy-five in the command, they set out on the march. The general course of travel was west, on the dividing ridge between the waters of Trinity and Red rivers, on the old Chihuahua trail. They had occasional accessions to their ranks, and learned on the first of May that the news of the expedition had been published in the Missouri papers. At length, after various adventures amid the splendid scenery of the prairies and the Wachita mountains, on the 27th of May, to their great joy, they reached the Arkansas river, and encamped on its right bank, about forty miles below the crossing of the Santa Fe trail. At this time they had a scanty supply of provisions, and were in want of a proper knowledge of the country they were in, and of the distance to their place of destination. Some of them were sick, and borne on litters; others, whose horses had been lost or died, were on foot. Yet they were cheered by the sight of the river. On the following day they sent spies across the stream to search for the Santa Fé road, who returned and reported it to be eight miles distant, on the opposite side. Fresh signs of extensive travel were seen on the road, but it was unknown whether they had been made by the Mexicans or by Bent's people, who had a station one hundred and fifty miles higher up. Near the Arkansas crossing they met some of Bent's men, who informed them that the Mexican caravan was expected to pass, on its way to Santa Fé, in about eighteen days. They were also informed that the caravan was guarded by five hundred Mexican soldiers as far as the United States boundary-line, and that those troops were in that vicinity, waiting the return of their merchants. On the 2d of June, a partnership was proposed by the Bents. They offered to "put in" forty men at that time, and forty more shortly afterward; and were to have a pro-rata share of the spoil: but, in a few days afterward, the Bents sent word that they could not comply. The Texan spies, who had gone out to look after the enemy, reported six hundred. The advance of the latter took one of the Texans prisoner; but he passed himself off for one of Bent's men, and they released him. The Texans remained in the valley of the Arkansas some time, recruiting, drilling, and hunting for the enemy. On the 9th of June, they took a Mexican prisoner, from whom they learned that an express went from Texas to Council Grove, and informed the traders of the advance of Snively's expedition; but that the former, having procured two hundred United States dragoons to guard them across the boundary, would pass on.

On the 17th of June, the Texans received news of the caravan. It was advancing, "composed of sixty wagons, and seventy-five hundred weight of merchandise." About fifteen of the wagons belonged to Americans, and the whole was guarded by three hundred United States dragoons, under the command of Captain Philip St. George Cooke. On the 20th, while the Texans were awaiting the arrival of the rich prize they had come to find, they met with a detachment of the enemy. The latter secured a good ravine, the only one for miles around in the prairie. The Texans immediately charged them, each one advancing according to the speed of his horse. Some of the Mexicans fled; the others, after discharging their pieces, surrendered. Those who fled were pursued, and three of them killed. The victory showed an aggregate of seventeen killed, and eighty prisoners, eighteen of whom were wounded. The Texans sustained no injury whatever, and from the spoils supplied themselves with horses, saddles, and arms, in abundance.

The Texans marched with their prisoners to a good "water-hole," where they remained until the 24th of June. On that day, about three hundred mounted Indians rushed into their camp at full speed, and one of the picket-guards fired at them, but they proved to be friendly. About this time the Texans began to be dissatisfied, and desired to return to their homes. This dissatisfaction continued; and on the 28th, when the spies came in, and brought no news of the caravan, it was greatly increased. About seventy of the men withdrew from the command, and elected Captain Chandler to lead them home. Three more of the wounded prisoners having died, the others were furnished with arms to keep them in meat, the wounded with mules to ride, and the whole of them set at liberty.

Captain Chandler with his party set out for home on the 29th of June, and Colonel Snively with the remainder proceeded up the Arkansas, to hunt game, and await the caravan. On the 30th, a party of Snively's men crossed to the left bank of the river, to kill buffaloes. They were discovered and run in by the advance of Captain Cooke's dragoons. That officer soon came up with his entire force, consisting of one hundred and ninety-six men, well mounted and equipped, and two pieces of artillery. He sent for Snively to visit him, and asked to see his papers, which were shown to him; whereupon he said to Snively that he believed the Texans were encamped on the territory of the United States.* Cooke then consulted with his officers, and they were of the same opinion. He then informed Snively that the Texans must be disarmed. Snively protested, and gave his reasons why the Texans were on their own territory. Cooke replied that "he had made his terms, and to them the Texans must submit." He further said that, "if one of Snively's men attempted to escape, he would throw his shells into their encampment, and send his dragoons across the river to cut the command to pieces."*Snively's report to the Secretary of War, July 9, 1843.

Captain Cooke then crossed over the Arkansas with Colonel Snively, and with his dragoons surrounded the Texan camp, lighted his port-fires, and ordered the Texans to stack their arms, which they did, asking to be received as prisoners-of-war. Cooke told them he had made his terms, and they must submit to them, or they should receive worse. This he said to them after they were disarmed. Cooke then recrossed the river, leaving with Snively's command of a hundred and seven men only ten muskets! The Texans were thus left, surrounded by Mexicans and Indians, six hundred miles from home, though on the soil of Texas, the easy victims of the first-comer. After a night's reflection, Cooke saw that such inhumanity would not do, and, on the morning of the 1st of July, he sent for the men, and offered to escort as many of them as wished to go to Independence, Missouri. Some fifty of the Texans took this route, and received three of the ten muskets left with the entire command. The balance refused an escort, unless they were guarded home. Cooke then ordered the Texans to leave the territory of the United States as soon as possible, and departed.

Colonel Snively now sent an express to Captain Chandler, and set out for Elm creek, about eight miles distant, and joined the latter on the 2d of July. Spies were sent off to look after the caravan, as the Texans did not care to give up the main object of the expedition. On the 4th, the Indians stampeded their horses, and took off sixty head. The Texans pursued the savages, and killed ten or fifteen of them, having one of their own men killed, and another wounded. On the 8th, the spies brought news that the caravan had crossed the Arkansas, and was on its way to Santa Fé. Snively, finding nearly all the men that had set out for home under Chandler unwilling to pursue it, resigned his command on the 9th of July. Chandler and his party set out for home. It is proper here to state that, by a previous understanding, the fifty men who went with Cooke were to return and join their comrades. They started, but, meeting some other Texans, they all returned to Cooke's command except fourteen.

The Texans now made a trial for volunteers to go after the caravan. They raised eighty-two men, elected Captain Warfield to the command, readopted the Georgetown by-laws, and set out on their march. Seventeen of them faltered, and returned with Chandler; the balance proceeded after the caravan. On the 18th, they struck a fresh trail, believed to be of a large body of Mexicans, under Governor Armijo, who were escorting the merchants. The Texans, fearing that they would be overpowered, abandoned the further pursuit, and started for home. On the following day, Captain Warfield resigned, and Colonel Snively was re-elected to the command. On the 20th of July, the Texans had a skirmish with the Camanches; and, on the 6th of August, after great privation and suffering, they reached Bird's fort, on the Trinity. Thus closed the Snively expedition.**The Texan government made an earnest complaint against this violation of its territory by Captain Cooke, and the president of the United States ordered a court of inquiry to investigate the matter. That tribunal assembled at Fort Leavenworth, and decided that Captain Cooke had acted within the line of his duty, and that he had disarmed the Texans within the territory of the United States. Notwithstanding this decision of the court, however, it turned out that Captain Cooke had invaded the territory of Texas, and had there disarmed the Texans. The Congress of the United States subsequently acknowledged the illegality of Captain Cooke's proceedings, and made a trifling appropriation to the Texans engaged in the expedition. — General Order, U. S. Army, No. 19, April 24, 1844. In reference to the surrender of the Texan rifles, Snively's party would certainly have perished had they not taken the precaution to secrete some of their good rifles, and deliver over the escopetas which they had taken from the Mexicans. This will account for their ability to pursue the caravan, and to pass through the country of the Camanches. — S. A. Miller's Journal: MS.