Steward A. Miller* and the Snively Expedition of 1843

The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume LIV, No. 3, January, 1951

Author: H. Bailey Carroll

*The diary upon which this account is based is the property of Miller's daughter, Mrs. C. C. Comer of Carthage, Texas, through whose kindness this study was made possible. All direct quotations from the manuscript are printed in this article in italic type.

Out of the eddying tides of Texas history that produced an Anglo-American infiltration, a Texan Declaration of Independence against Mexico, the Alamo, San Jacinto, the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, General Adrian Woll's raid on San Antonio, and the Mier Expedition, the Snively Expedition of 1843 is but a logical link in a long chain of circumstances connected with the Westward movement and the clash of Anglo-American Texans with Mexicans.

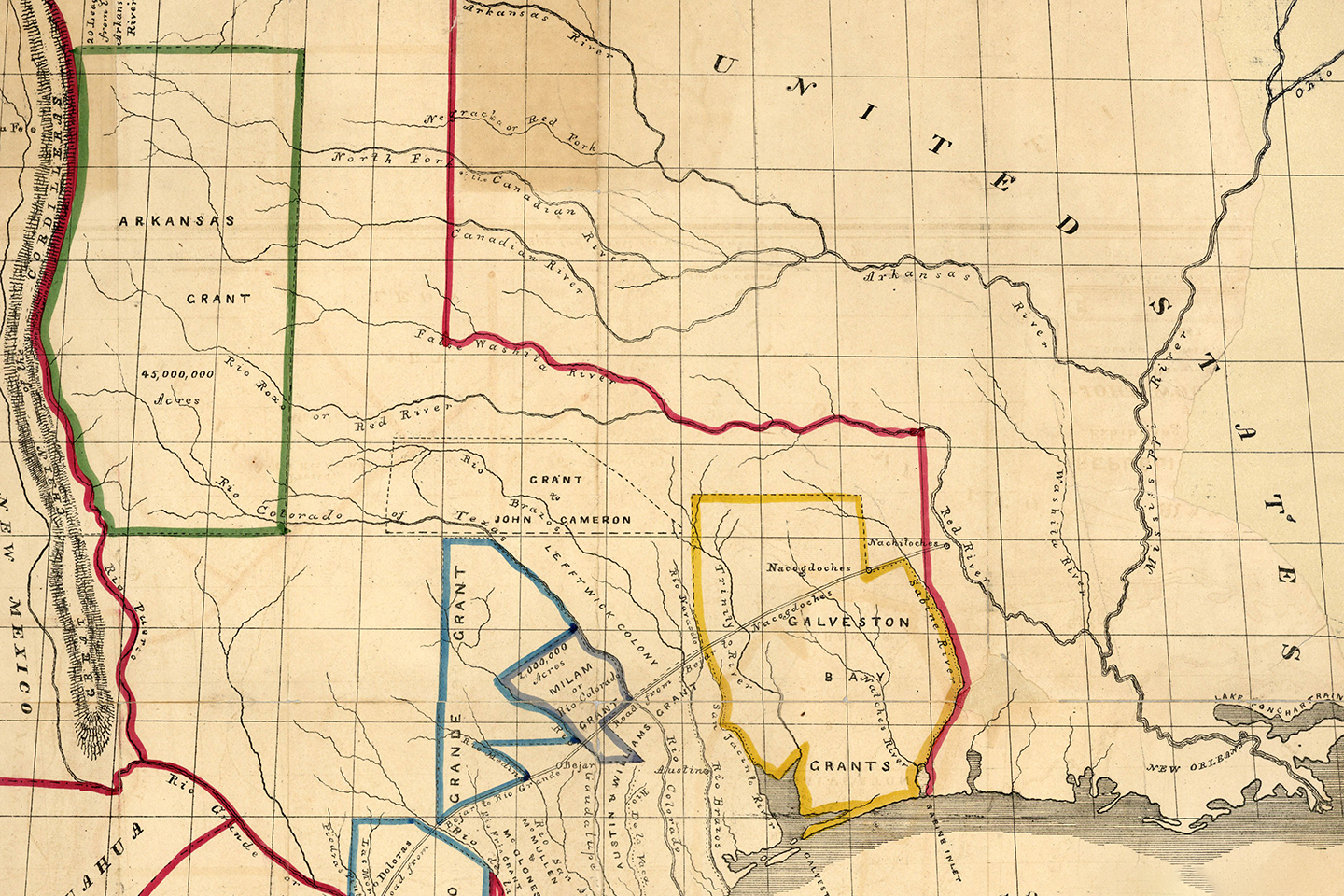

On December 19, 1836, the Congress of the infant Republic of Texas passed an act defining the boundaries of the nation.1 The statute accepted the Adams-Oñis Treaty line of 1819 as the eastern and northern boundary2 and claimed as the southern and western boundary the Rio Grande from mouth to source and thence due north to the 42nd parallel. This line, which extended far beyond the edge of Texas settlement, included portions of the present states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming as well as the city of Santa Fe and other settled portions of New Mexico. In 1841 President Mirabeau B. Lamar made the first attempt to extend Texan jurisdiction into this area by authorizing the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, but far from achieving its objective, the expedition was captured in eastern New Mexico and its members marched as prisoners to Mexico. The immediate result was the Adrian Woll raid on San Antonio and the Somervell and Mier Expeditions, each of which lowered rather than raised Texas' expansionist ambitions and even threatened her chances of survival.1H. P. N. Gammel (comp.), The Laws of Texas (10 vols.; Austin, 1898), I, 1193-1194.2The Adams-Oñis Treaty of 1819-1821 fixed the western boundary of the Louisiana Purchase (the boundary between Spanish possessions and the United States) as beginning at the mouth ot the Sabine River and extending along its south and west bank to the 32nd parallel and thence directly north to the Rio Roxo or Red River; "then following the course of the Rio Roxo westward to the degree of longitude 100 west from London and 23 from Washington; then, crossing the said Red River, and running thence by a line due north to the river Arkansas; thence following the course of the southern bank of the Arkansas to its source, in latitude 42 north; and thence by that parallel of latitude to the South Sea. The whole being as laid down in Melish's map ot the United States."—William M. Malloy (comp.), Treaties, Conventions, International Acts, Protocols, and Agreements between the United States and other Powers, 1776-1909 (2 vols.; Washington, 1910), II, 1653. The Mexican state of Texas (Coahuila y Texas) inherited this boundary, and after the accomplishment of Texan independence, Red River, the 100th meridian, and the Arkansas became important landmarks establishing the boundary between the United States and the Republic of Texas. The map referred to is one accompanying John Melish, A Geographical Description of the World, Intended as an Accompaniment to the Map of the World on Mercator's Projection (Philadelphia, 1818). The map is copied in Texas vs. United States, United States Reports (1896), 30-31. The United States recognized the Republic of Texas in March, 1837, and by a treaty of April 25, 1838, definitely specified the Adams-Oñis Treaty line as the boundary between Texas and the United States. Malloy (comp.), Treaties, Conventions, ... between the United States and other Powers, II, 1779.

This was the situation when, on January 28, 1843, Jacob Snively petitioned the government of the Republic for permission to organize and fit out an expedition for the purpose of intercepting and capturing the property of Mexican traders who might pass through Texas' claimed territory on the Santa Fe Trail.33The Santa Fe Trail, which extended from United States settlements in Missouri to the Mexican town of Santa Fe, became important as a commercial route in 1821, and by 1843 the total volume of trade was estimated at $450,000 annually. Lansing B. Bloom, "Editorial Notes," New Mexico Historical Review, IX (1934), 97. The classic account of the Santa Fe Trail is Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies: The Journal of a Santa Fe Trader (2 vols.; Philadelphia, 1855; 1 vol. reprint; Dallas, 1935).

Snively, a former citizen of the United States, probably a Pennsylvanian, had come to Texas at least as early as April, 1835, when he was acting as surveyor for the Mexican government. In July of that year he was granted land in David G. Burnet's colony. Snively served in the army of the Republic from March, 1836, until September, 1837, rising in rank from lieutenant to colonel. After his discharge from the army, he continued to work with the War Department, holding the position of paymaster general and acting as secretary of war for several months during the summer of 1837.4 At the time of his petition he was still in government service having been appointed by President Sam Houston to "perform the duties of adjutant and inspector general of the Republic of Texas, together with those of paymaster and quartermaster of subsistence, under orders of the secretary of war."54For biographical information on Snively see Petition 208, Bound Volume XIX, p. 645, grants filed in General Land Office; a photostat of a "Biographical Intormation Sheet" sent by Carl Hayden, United States senator from Arizona, to Miss Harriet Smither, Texas State Archives; Army Papers, 1836, Texas State Archives; Comptroller's Military Service Records, Texas State Archives; Muster Roll, Army of the Republic, copy in General Land Office; Bounty Warrant, No. 108. General Land Office.5Houston to Snively, February 5, 1843, Army Papers, 1840-1845, Texas State Archives.

Snively's proposal to organize a force which would attack Mexican caravans on the Santa Fe Trail does not appear unusual when viewed in its proper historical setting. Letters of marque and reprisal are no longer issued by recognized governments, but such was acceptable practice a century ago. One must know the times. These were the Roaring Forties in the United States, and they were likewise the Roaring Forties in Texas. Mexico had refused to recognize the independence of the Republic of Texas and had continued to carry on a state of war.

It is not surprising then that a person of Snively's prominence should be granted the permission to organize a retaliatory force. As a matter of fact, the Snively episode was so much lacking in the unusual to its contemporaries that it was usually described in the Texas of the 1840's as the second expedition to Santa Fe. Of course neither the 1841 expedition, with which George Wilkins Kendall was associated, nor the 1843 party actually reached Santa Fe, but both were Texan thrusts toward the northwest and potentially both might have had the New Mexican capital of Santa Fe as an ultimate objective. Snively received his authorization in a letter dated February 16, 1843. The commission read:

To

COL. JACOB SNIVELY

Sir:

Your communication of the 28th Ulto., soliciting permission from the Gov't. to organize and fit out an expedition for the purpose of intercepting and capturing the property of Mexican Traders who may pass through the territory of the Republic, to and from Santa Fé &c., has been received, and laid before His Excellency the President [Sam Houston], and he, after a careful consideration of the subject, directs that such authority be granted you, upon the terms and conditions therein expressed,—That is to say,

You are therefore, hereby authorized to organize such a force, not exceeding three hundred men, as you may deem necessary to the achievements of the objects proposed.

The expedition will be strictly partisan, the Troops composing the corps to mount, equip, and provision themselves at their own expense, and one half of all the spoils taken in honorable warfare, to belong to the Republic and the Government to be at no expense whatever on account of the expedition.

The force may operate in any portion of the Territory of the Republic, above the line of settlements and between the Rio del Norte and the boundary line of the United States, but will be careful not to infringe upon the territory of that Gov't., as the object of the expedition is to retaliate and make reclamation for injuries sustained by Texan citizens, the merchandise and other property of all Mexican citizens will be a lawful prize, and such as may be captured will be brought into Red River, one half of which will be deposited in the Customs House of that District, subject to the orders of the Government, and the other half will belong to the captors, to be equally divided between the Officers and men. An agent will be appointed to assist in the division.

The result of the campaign will be reported to the Government upon the disbandment of the force, as also its progress from time to time, as practicable.

By order of the President

M. C. HAMILTON

Act. Sec. War & Marine66The original document is in Army Papers, 1840-1845, Texas State Archives; it is printed in George P. Garrison (ed.), Diplomatic Correspondence of the Republic of Texas, Annual Reports of the American Historical Association for 1907 and 1908 (3 vols.; Washington, 1908-1911), II, 217.

The Snively Expedition is a chapter which Texas history ought to be happy to record in detail; it typifies Texan enterprise of its era and merits recognition as a forerunner of the settlement of the Anglo-American Southwest. Its story is one of scouting, of freebooters, of privateers who carried their letters of marque and reprisal across a sea of grass to attack the mercantile trail most outstanding in the memory of Americans. That the particulars of the expedition should be almost unknown in American annals may at first seem surprising.

It was not prejudice, maliciousness, or a lack of scholarship which caused the Snively Expedition to be neglected, but only that the material was not available to those who might have put the incident in its rightful place a century ago. The aphorism, "No document, no history," could not be more true than in connection with the Snively Expedition. The Texan Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 had George Wilkins Kendall; the Mier Expedition had Thomas Jefferson Green; the Snively Expedition, too had its historian, but his work has been in private hands for more than a century.

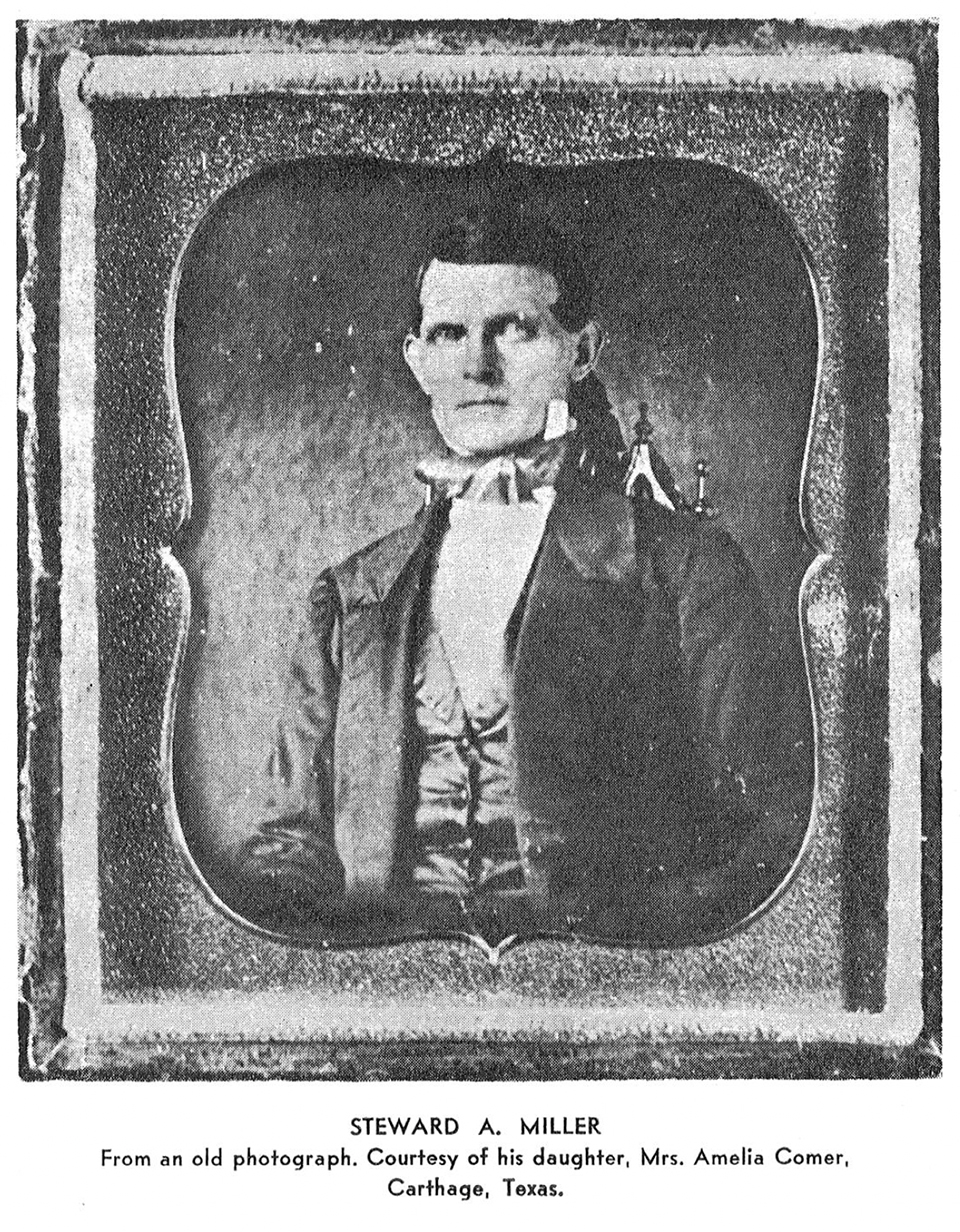

One of the persons who responded to Snively's call for men to participate in the partisan expedition was Steward Alexander Miller. A native of Virginia, he had come to Texas in 1839 and settled in Crockett, Houston County, where he established a business and began the study of law. He was thirty-seven years old at the time he set out to join the expedition.77A. A. Aldrich, The History of Houston County, Texas (San Antonio, 1943), 175-176.

Although apparently it was not his habit to keep a diary, Miller did take with him on the trip a little account book and a stack of unused ballots on which he recorded each day's progress and events. The journal which he kept is the torch which illuminates the Snively Expedition and makes it possible to bring the incident from comparative obscurity to light. This unquestionably was its purpose, for on the site of present Gainesville, Texas, Miller wrote:

I am now sitting on the naked Bank of the greatest river for navigation in the Republic, acting in the double, yea, tribble capacity of a fisherman, a soldier, and a noter of events and materials for some future historian.

Here were high purposes and a definite sense of history, and Steward A. Miller is entitled, after the lapse of more than a century, to be known as the historian of the Snively Expedition. It has been said that "the preservers of history are as worthwhile as the makers." Miller was both a maker and a preserver of history; he did not attempt to complete his task alone, but he did preserve the account.8 If he is not to the Snively Expedition what Josiah Gregg was to the Santa Fe Trail, he is, at least, entitled to wear a Jacob Fowler mantle—not a mean tribute in itself.8Probably the last survivor of the Snively Expedition, Miller lived a well-ordered, useful, and exemplary life. After his death on March 27, 1893, his diary passed into the hands ot his daughter, Amelia, Mrs. C. C. Comer of Carthage, who not only made the diary itself available to the present writer but also furnished him with other information regarding her father, including letters, pictures, and newspaper clippings.

Miller's entries in the diary are apt throughout, and after more than a hundred years his account remains as clear, as fresh, as flavorful as the day it was written. Miller is a charming philosopher, conscientious in the extreme, and by nature inclined to be objective. He tells a fair and impartial story, already by temperament the judge that he was later to become on the bench.9 No keeper of a log ever gave greater fidelity to his undertaking. Occasionally in writing Miller would delete a word and add another, but every deletion may be clearly read. In writing he made every effort to be correct, but all of his corrections are immediate. On any given day he recorded the facts as he saw them. In the days following he might learn of an error, but what he had already written was sacred. He would not change copy, but instead would note the error on the day on which he learned of its existence.9After his return from the Snively Expedition, Miller studied law with James Carr, probably the first lawyer to locate in Crockett, and soon became associated with Judge Royall T. Wheeler. Miller represented Houston County in the First and Second Legislatures in 1846 and 1847 and was a member of the Texas Senate in 1851, 1854, and 1861. He later served two terms as judge of Houston County. Aldrich, The History of Houston County, Texas, 175-176.

Miller was one of the first to arrive at the appointed place of rendezvous, Fort Johnson at the little settlement of Georgetown near Coffee's Station on Red River in what was then Fannin County.10 He was probably in many ways representative of the Texans who gathered there. Certainly, even though every member of the expedition can not be identified, enough is known of the personnel to assert with assurance that the men of the expedition were, in the main, plain, ordinary, everyday citizens of the Republic of Texas organized as a legal part of the army and commissioned to do a special job of retaliating on the Republic's enemies.1110The area is now included in Grayson County, which was created out of Fannin in 1846. Gammel (comp.), Laws of Texas, II, 1313-1314. The site of Fort Johnson was marked by the Texas Centennial Commission in 1936. The inscription on the marker reads: "Site of Fort Johnson, Established by William G. Cooke in 180 as a part of the detense of the military road from Red River to Austin. Named in honor of Colonel Francis W. Johnson (1799-1888), commander of the Texas army at the capture of San Antonio, December 10, 1835. Place of rendezvous of the Snively Expedition which set out on April 25, 1849. The settlement in the vicinity was known as Georgetown."—Monuments Erected by the State of Texas to Commemorate the Centenary of Texas Independence (Austin, 1938), 134.11The legality of the Snively Expedition was established beyond dispute with the publication of William C. Binkley's scholarly study, The Expansionist Movement in Texas, 1836-1850 (Berkeley, 1925), 115-116.

On April 24 the expedition was organized into three companies, and Snively was unanimously chosen as commandant. On the following day the recruits were put through one parade whereupon the induction and training period was over and the partisan force was ready to march. On this day Miller wrote:

Started from Ft. Johnson in Fannin County. Our numbers not exactly assertained, say 160 to 170 rank & file.12 On being peraded at 10 o'clock to start, the laws & regulations, drawn up by the committee appointed by the Col. Commandant on yesterday for the government of the expedition, were submitted to the men & officers for their reception, & unanimously adopted. The order to perade & march was obeyed with alacrity; the countenance of each individual indicated a determined resulution (which was expressed in so many words by many) never to surrender their arms but, if he must be taken, he would be taken wheltering in his own blood at the breach of his gun. The most of the men are hardy Frontiersmen, inured to toil and danger, & the use of arms. They are furnished generally with a rifle, breace of pistols, & Bowie Knife, many of them have a pair of holsters & several brace of pistols besides. That such men thus accutred, equiped, and determined should effect the object of their tour is almost beyond doubt.12Snively gave the number as 177.—See Snively to M. C. Hamilton, June 28, 1843, Army Papers, 1840-1845, Texas State Archives. T. C. Forbes and Gilbert Ragin, members of the expedition from the Clarksville area, reported after their return that the force started out with 176 men. See Northern Standard (Clarksville), August 1 and September 14, 1843 (reprinted in Niles' National Register [Baltimore], August 26, 1843; Red-Lander [San Augustine], September 8, 1843; Morning Star [Houston], October 3, 1843; and Telegraph and Texas Register [Houston], October 4 1843). It is possible that some of the figures given include men who later joined the expedition on the line of march. On May 3 Miller reported that a fourth company was formed out of new arrivals.

On departure the members of the Snively Expedition, calling themselves the Battalion of Invincibles, exhibited a characteristic Texas spirit. Even the fact that they were setting out on a journey which was for the most part across uncharted lands caused them to anticipate no great difficulty, possibly they even considered themselves fortunate that there were among them those who knew the nature of the first section of the country over which the expedition was to pass. There is no evidence available indicating that any member of the group had ever gone the whole distance between the Red and the Arkansas along a route anything comparable with the one proposed for the Snively force, but some general geographic information was common knowledge. The Texans knew, for example, that there were no physical obstacles such as forbidding forests or impassable mountains which would have to be encountered and that there were no rivers which could be expected to give them other than temporary or minor difficulties. In the main the route would stretch across the Great Plains. Such hazards as swollen streams, quicksand, rattlesnakes, stampedes, and scarcity of water and food were to the Texan voyagers only everyday, to-be-expected elements in frontier travel.

The sore-backed and sore-footed horses of the Snively Expedition cut a shallow and quickly obliterated trail across the western plains. This study is an attempt to brush the dust of more than a century from the hoof marks along the trail and to put a fair interpretation on the events of the expedition as they may be reconstructed.

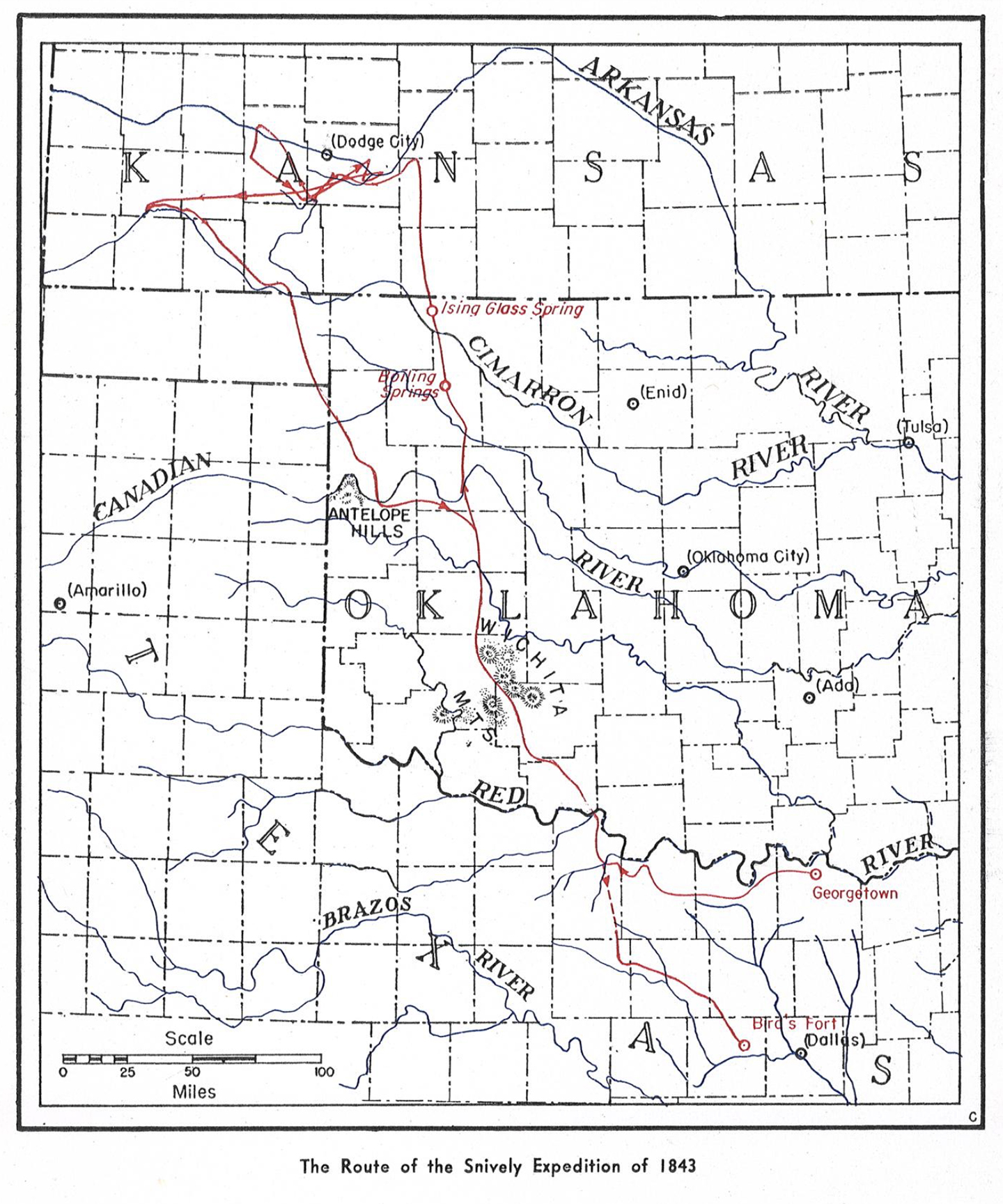

Snively's commission had cautioned that his force must not transgress upon the lands and territory of the United States, and Snively appears to have made a studied attempt to follow instructions. His first objective was to direct the course of the expedition westerly along the vicinity of the south bank of Red River until certain that the force was beyond the 100th meridian. On May 5, the eleventh day after leaving Fort Johnson, Snively, convinced that he was at least fifty miles west of the 100th meridian, ordered the force across Red River.13 Miller's day-by-day account with mileage estimates and stream description makes it possible to identify the line of march as having been across the present Texas counties of Grayson, Cooke, Montague, Clay, and into Wichita County to a point about two miles below the mouth of the main Wichita River, where there is a natural crossing place which readily fits Miller's description of the crossing, for he wrote: We crossed the river generally on foot, leading our horses. Red River at that point has almost no banks; the valley broadens and the stream spreads out over a wide area. This crossing place was used by Captain Randolph B. Marcy in 185214 and later became the main crossing on the road to Fort Sill.15 In times of normal flow the river is still fordable there.13Snively to George W. Hill, July 9, 1848. The original letter is in Army Papers, 1840-1845, Texas State Archives; it is printed in Garrison (ed.), Diplomatic Correspondence of the Republic of Texas, II, 218. It should be noted that the Melish Map (see note 2), the recognized authority in 1843, located the 100th meridian approximately sixty miles east of the true meridian.14Randolph B. Marcy, Exploration of the Red River of Louisiana (Senate Executive Documents, 32nd Cong, 2nd Sess. [Serial No. 666], Document No. 54), 7. The ford was actually about one hundred miles east of the true 100th meridian.15Copies of Federal Government plats of January, 1874, and August 4, 1874, in Cotton County Abstract Company, Walters, Oklahoma, show this crossing, which is at the beginning of the Byers Bend of Red River.

After four days of north northwestward travel across the present state of Oklahoma, the Texans reached an area with the most picturesque terrain thus far encountered. Miller was eloquent in his description:

[May] 10th (Wednesday)...Today we drew up by degrees nearer and nearer to the Witchata Mountain[s]. Though the country has been romantic for several days, this far excells any. On the right a rugged mountain, whose keen peaks seem to pierce the verry skies, while beneath is beautiful level prairie valley, rich & covered with a thick coat of muskeat grass, upon which numerous herds of buffalow feed in quietness or run in wild confusion. Presently as we pursued the valley (which forms a gap in the mountain) appeared far in front other mountains, whose distance gave them a deep blue colour, while on the left, not quite so far removed other mountains hove in sight. The various mountains presented a thousand different colours of the richest hue, according to their position to the sun & to us, while they sent down through the delightful valley on which we were travelling, numerous rivulets & small branches of [pur]est freestone water. ... To heighten all this is a healthy climate. We have a clear sky & a continual current of fresh air charged with the sweet mirads of prairie flowers. What a field for the painter of rich scenery!! The only unfavourable feature of this country is that it has not quite a sufficiency of wood for fuel. For building there is an abundance of rock.

The mountains were entered on May 10 at the gap above the present station of Odetta and west of Eagle, Bat Cave, and Charon Garden mountains—all peaks in the Wichitas. Just as surely as the expedition organized at Fort Johnson, did it go through the Wichita Mountains along the Cooperton Gap. The Cooperton Gap thus becomes a "bench mark" for the trail. It must be noted that the expedition went through a pass—there were mountains on both sides; this means that the Wichitas were not skirted as they might have been without too much difficulty either to the east or to the west. The Cooperton Gap, extending between the main body of the mountains and western outliers, is a pass without a perceptible climb, and it is identifiable by the distinctive plum-blue colored haze ahead. The Cooperton Gap is the only way through the Wichitas which has this characteristic—a phenomenon which gave its name to Blue Mountain, situated about a mile north of lofty Baker Peak, Miller's "rugged mountain" which reaches an elevation of 2,457 feet.

Originally the Cooperton Valley was a part of the Kiowa and Comanche Reservation. When the area was thrown open to white settlement, the grass was still "belly deep on a good horse." It was a buffalo shangri-la; thus it was in keeping with the fitness of things in nature that the Snively Expedition moving through this buffalo land should be skirting what would become the western boundary of the Wichita Mountain Wildlife Refuge, where probably more has been done to preserve the buffalo than at any other one place in the nation.

The expedition probably camped for the night in the vicinity of the present headquarters of the well-known O + Ranch, where the absence of timber and the "abundance of rock" led the W. A. Fullingims, father and son, to build out of native stone one of the most colorful ranch homes in western America. The "healthy climate" which Miller noted is also borne out, for in 1947 the elder Fullingim was ninety-three, his wife was ninety, and their hale and hearty son, aged seventy, was then "beginning to take over a lot on the ranch."

Miller's daily record of direction and estimate of mileage traveled in addition to his descriptions make it possible for each camp site on the trail to be identified with at least a major degree of accuracy. The locating of each camp site with relation to the one before and the one which was to follow might, however, be open to question were it not for the fact that occasionally the route crossed areas so distinctive as to be impossible of duplication. These key points are definite trail locations and substantiate all the routing that has gone before. Such a key point was the Cooperton Gap, and another was encountered thirteen days later when the Texans camped on the north side of the Cimarron River near an excellent spring and a cave which Miller named Ising Glass. At this camp, he wrote:

[May] 24th (Wednesday).. I shall call this place "Ising Glass Spring" from the fact that the bluff out of which the spring issues is nothing more nor less than huge ledge of Ising Glass. .. Today a party of us amused ourselves much by exploring a cave which enters into this Ising Glass bluff. It may be entered by three different doors & passages which connect themselves at the distance of some 60 or 80 ft. from the mouth. We penetrated this cave some 600 ft. at which point it became too dark to advance farther without the aid of better lights, those we had being only chunks of fire. In some places we went in a stooping position, while in others again we walked erect. The christilization of Ising Glass & other substances in this subterraneous retreat present a beautiful view representing sparkling gems as you enter about 20 paces from the mouth, by the reflection from the mouth against them. We found, in our voyage, decaid animal matter, & scull & other bones which were supposed to be that of a panther. We found a small pool of water at the distance of some 150 paces from the mouth. This cave no doubt extends a distance of a mile or more.

This gypsum cavern, infrequently visited and largely unknown, remains after a century just as it was when Miller explored it. It is located on ranch property about eight miles south of the Oklahoma-Kansas line and three miles north and two miles west of the bridge over the Cimarron on Highway 64 between Alva and Buffalo, Oklahoma. The spring is still flowing, and the three entrances to the cave which converge about seventy-five feet within the interior are still intact.

After a month and two days in regions but little better known than in Coronado's time, the Snively party on May 27 reached its prime geographic objective, the Arkansas River. Somewhere in the vicinity of the Arkansas it was expected that rich Mexican caravans plodding along the Santa Fe Trail would be encountered and seized. In crossing the arid region and sand dunes south of the Arkansas, Miller felt that enduring fascination and eternal beauty and charm which have for so long bound men to the desert. Not only does Miller give good topographic notes on the reaching of the Arkansas, but he also pictures vividly the emotional relief experienced by the column at the end of the first phase of the long march.

[May] 27th (Saturday) 20 mis. N. 15° W. to the Arkansas River & camped on its S. E. Bank. This River affords the first good water we have had since our encampment of the night of the 25th inst., a distance of 45 miles. Within this distance we found a little water (or as the men vulgarly called it "Bufalow Eurine") in little muddy holes which, however, if not replenished by rains must dry up in a few days.

The first part of our day's travel, was over a high roling prairie, of rather a thin sandy quality. After which we entered what is designated on the map as the "Sand hills." These "sand hills" will probably compare with the famous "Desert of Arabia." The distance through these sand hills is various estimated at from 3 to 6 miles. Within this space one hill is quickly followed by another. These hills are composed of pure white sand, nearly as fine as wheaten flower. The hills are generally entirely bare; others give growth to a few spears of course grass. The wind, which allways blows more or less in the prairie, seemed this evening to have acquired additional force. The numerous clouds of sand, born aloof from a thousand hills, by the force of the winds, present a sublime view, of the works of the God of nature. I can liken it to nothing more illustrative than the drifting of snow, in the mountains of a northern climate. These hills, I have no doubt frequently shift their localities, valleys taking the place of hills, & hills taking the place of valleys. The sand hills being bare & white may be seen at a considerable distance.

While passing through these hills the following mellancholly reflections passed over the mind. We are now at from 500 to 1,000 miles from our respective homes, with but a scanty supply of provisions, in want of a proper knowledge of the country we are in, or of the distance to the place of our destination. Some of us sick & borne on litters. Others a foot for the want of horses, which have been lost, died, or jaded with fatigue. All suffering for want of water & one of our number having been killed, or captured by the savages. Surrounded with nothing but sand hills, with here & there a lonely cotton wood tree, we despared of reaching water. Thus while experiencing present & anticipating future wants & embarrasments, we mounted the sumit of the last sand hill, when of a sudden was presented to our delighted visions one of the most beautiful prospects in nature. The great Arkansas River about 1 mile wide at this point rolling its sweet waters, majestically to the East, a beautiful valley 600 yds. in width, clothed with green grass & a few cotton wood trees, beyond the River a vast level plain, extending as far as vision can reach, covered with green grass, with scores of buffalow & elk, feeding thereon. What a contrast!! One minute ago in the midst of suffering & want, with gloomy & disparing prospect a head. Now surrounded with plenty & cheered with bright prospects. (The R. here has low bank, & is fordable). Our present wants relieved. The clouds of dispare, whose lowering had occasioned a general gloom, dispelled. Barren & steril hills exchange for a blooming valley, flowing with water. We were boyed up with hope.

The line of travel described by Miller on this and previous days makes it possible to locate the point at which the expedition struck the Arkansas as the southwestern corner of present Edwards County, Kansas, about twelve miles southwest of Kinsley and a few miles downstream from the beginning of the Great Bend of the river.

Upon reaching the Arkansas, the first objective of the Texans was to orient themselves with their physical surroundings. They knew, of course, that the Santa Fe Trail paralleled that section of the river and Miller's diary reveals that they had some knowledge of the division of the trail16 and of the location of Bent's Fort,17 but apparently most of their information was hearsay. The spy company immediately became active while the main command moved from camp site to camp site along the south bank of the river. Late on May 30 the Texans' hopes were aroused by the discovery of evidence of a wagon train. Miller wrote the details of the incident in his entry for May 31:16The Santa Fe Trail divided at the present village of Ingals in western Kansas, the Plains Branch (or Cimarron Cut-Off) crossing the Arkansas and extending in a more nearly direct line toward Santa Fe and the Mountain Branch continuing along the northern bank of the Arkansas to the vicinity of La Junta, Colorado, before turning southwestward through Raton Pass New Mexico Historical Review, IX (1934), 87; Joseph C. Brown, "Field Notes of the Santa Fe Trail Survey," Eighteenth Biennial Report of the Board of Directors of the Kansas State Historical Society (Topeka, 1913), 117-125.17Bent's Fort was established about 1832 by William Bent and partners on the north bank of the Arkansas about seven miles east of present La Junta, Colorado. The fort was a highly important point on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail and possibly the most outstanding trading post of the Southwest. Dictionary of American History (5 vols.; New York, 1940), I, 178-179; George Bird Grinnell, "Bent's Old Fort and Its Builders," Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, XV (1919-1922), 28-87.

31st (Wednesday) After writing down the moves of the army yesterday, two of our spies returned in great haste, with the intelligence that "they had espied some 8 or 10 waggons, a number of horses & men, who had just crossed the river & encamped on its left bank. They reported that this might be a part of the expected Carry Vans, or that it might be the men and property of Mr. Bent, the American gentleman who has a station & a number of trapers in the Rocky mountains." Upon receipt of this intelligence the Army was ordered to take up the line of march immediately, which was obeyed not only with alacrity, but enthusiastically. This was about sunset, & by a forced march of 35 miles up the right bank of the Arkansas River, we met the remainder of our spies before sunrise this morning. I should have stated, however, that 15 men out of each of our 4 companies, were detailed to remain with and guard the ammunitions & provisions, at our yesterdays camp. The main body of our spies report that two of their number have been into the encampment across the river & find that it is Mr. Bent's. From one of the Mr. Bents & company our spies learn that "the Chihuahua Carry Vans have passed on to the North about 2 months ago & not 10 days as before supposed. And that they are expected to return in about 16 or 18 days, &c, &c, &c. Here we grazed our horses & took a little refreshment & by a retrograde march down the right bank of the R. reached a small grove of cotton wood 16 miles from our mornings refreshment, making our whole march, since yesterday sunset, about 51 miles. A dispatch is set to bring up the detail of yesterday & baggage. We learn of Bent & Co. through our spies that the Carry vans that proceeded to the north 2 months since were guarded by 500 Mexican Soldiers as far as the boundary line between Texas (or as the Mexicans would say) Mexico & the U.S. A. They are lurking, it is said, in the vicinity of the said line till the return of the several carryvans from Independence & other parts of the U.S. to Santa Fee & Chihuahua. We also learn that a party of 12 Mexicans was recently attacked & all of them massacred, by Warfield, the Capt. of a band of about 23 men, who are ranging through these regions for the double purpose probably of traping & robing. It is said that from the massacred he obtained $12,000.

The meeting with the men from Bent's Fort was of considerable significance to the Texan expedition for it was by this chance encounter that Snively and his men were first apprised of two incidents which were to have a marked effect not only upon the outcome of the expedition but also upon its subsequent historical interpretation. Miller in writing of the day's events, either from misunderstanding or from misinformation, confused the two incidents: Charles A. Warfield's attack on Mora and the murder of Antonio José Chaves by John McDaniel. Miller later corrected his error, but since his time so many erroneous statements have been made—some malicious, some unintentional, and some deliberately sensational—and so often has the Snively Expedition been associated, much more closely than the actual facts warrant, with Warfield and McDaniel that it seems advisable to turn away from the main thread of the story to establish as far as possible the facts of the contemporary happenings which have been repeatedly thrust upon the Snively stage but of which the members of the Snively Expedition actually had no knowledge until they encountered the men from Bent's Fort on May 31.

On August 16, 1842, six months before Snively's commission was issued, the Texan government granted a commission to Charles A. Warfield, of Missouri, authorizing him to raise a force to operate against New Mexico or New Mexican commerce within the claimed territory of Texas.18 Warfield, however, was far from being as successful as he had anticipated. On March 21, 1843, he was at the head of a group of twenty-four mountain men. By May he was discouraged but not ready to give up; whereupon he marched on the New Mexican settlement of Mora. Five Mexican soldiers were killed, eighteen others captured, and seventy-two horses were taken. The prisoners were released unharmed, and a withdrawal was started, but the following day Mexican troops stampeded Warfield's horse herd and captured five of his men. Warfield and the remainder of his force, left on foot, walked back to the vicinity of Bent's Fort. No recruits had arrived and the force was disbanded.1918George W. Hockley to Warfield, August 16, 1842, in Senate Executive Documents, 32nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (Serial No. 660), Document No. 14, pp. 117-118.19Rufus B. Sage, Wild Scenes in Kansas and Nebraska, the Rocky Mountains, Oregon, California, New Mexico, Texas and the Grand Prairies (3rd ed., revised; Philadelphia, 1855), 247-267; reprinted by E. B. Burton, "Texas Raiders in New Mexico in 1843," Old Santa Fe, II (January, 1915), 314ff.

According to all the practices and rules of nations in 1813, Warfield's conduct had been entirely correct and proper,20 but from the viewpoint of the Snively Expedition, its effect had been detrimental. After Warfield got in the vicinity of Bent's Fort, the New Mexicans were bound to have been warned of the Texan plans. Warfield's descent upon Mora was especially unfortunate. No practical benefit had been achieved for Texas; nothing had been permanently seized; New Mexico had not been weakened by the puny blow; but instead, when the Snively Expedition, with its relatively strong contingent of about 180 men, had been on the way but a week or ten days and blithely was hoping to make some use of the element of surprise, some two dozen men put New Mexico on the alert.20The most scholarly account of the legal and diplomatic aspects of the Warfield Expedition is in Binkley, The Expansionist Movement in Texas, 1836-1850, 107-108.

The other incident which Miller confused with Warfield in his entry of May 31 may or may not be in a small measure traceable to Warfield, but certainly its effect at the eastern end of the Santa Fe Trail was at least as great as was that of Warfield's descent upon Mora at the western end. Before leaving Missouri, Warfield may have issued a captain's commission to one John McDaniel, described as "lately from Texas."21 Newspaper statements that McDaniel had such a commission do not prove that he actually did have, but granting, for the sake of argument, that McDaniel did have a commission from Warfield, the next question which immediately arises is: what authority did Warfield confer, and even more to the point, what could Warfield confer? In a normal course of events Warfield would have authorized McDaniel to recruit men and to meet him outside the limits of the United States. McDaniel did organize a band of fifteen men from Westport and Independence and set out ostensibly to join Warfield. On April 10, 1843, McDaniel and his party were on the Little Arkansas, unquestionably within the boundaries of the United States. There they intercepted Antonio José Chaves, a highly respectable merchant of Albuquerque, who with a few servants was going to the United States to trade. Chaves was robbed of a large sum of money and killed. Once the robbery was committed, McDaniel and his band lost all interest in and intention of joining Warfield, if indeed such was ever their plan. Instead, they turned back to the settlements. With some good fortune on the side of law and order, the crime became known almost immediately, and the parties were soon apprehended. It was quite natural that McDaniel, after being taken into custody, should try to give the best possible complexion to his act. In trying to cover his guilt, he played heavily upon his supposed Texan authority or connections.2221Niles National Register, August 19, 1843, quoting Missouri Reporter, July 31, 1843.22For various accounts of the Chaves aftair, see St. Louis New Era, April 29, 1843; Niles National Register, May 13 and June 10, 1843; Gregs, Commerce of the Prairies, 327; Grinnell, "Bent's Old Fort and Its Builders," Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 1919-1922, XV, 72-73.

Although McDaniel's act was unwarranted and done without knowledge of the Texan government, Warfield, or Snively, some of the newspapers of the United States began immediately to link all four together.23 It was a journalistic trick in propaganda. Anti-Texan and pro-Mexican historians have done much the same thing. One may be emotionally or morally opposed to land privateering or to privateering on the high seas, but both were in 1843 in accord with the practices of civilized nations. A state of war was being carried on by Mexico against the government and the people of Texas. Texas had tried to end it, but Mexico was unrelenting. So long as Mexico prosecuted war against Texas, the Texans had either to defend themselves by levying war against Mexico or to submit—and the Texans were not inclined to submit. The Texans, however, committed no act of brigandage nor did they ever contemplate doing so. The men of Snively's party were citizen-soldiers with full authority from their government to represent it in making reprisals against a government and a people engaged in making war on Texas. The Texas government was no more responsible for the act of John McDaniel than the government of the United States was responsible at a later date for Jesse James.23A notable exception to the general attitude of the press was that of the New Orleans Picayune (quoted in Telegraph and Texas Register, May 17, 1843, and in Northern Standard, June 15, 1843), which defended Warfield and questioned his being connected with any act of violence on United States soil.

In addition to the information on Warfield and McDaniel, the Texans probably also received advice from the Bent traders, for immediately after the encounter Snively moved his force south of the Arkansas, first to Mulberry Creek and eventually to the head of Crooked Creek, which Miller calling Winding Creek. This new position enabled the Texans to command the Cimarron Branch of the Santa Fe Trail and at the same time to screen their own presence in the country. The spies created a false alarm which caused the Texans to rush to the Arkansas on June 7, and they remained in that area at various camps above the point where the Cimarron Branch of the trail crossed the Arkansas until June 20, when Snively ordered the force to fall back to Crooked Creek. In the meantime, Warfield and three or four of his followers had joined the Snively party. In dropping back the Texans struck the Santa Fe Trail about fifteen miles below the crossing; there they found fresh tracks, and Snively immediately sent scouts to investigate. In a few moments they were back calling "Mexicans." In describing the battle which followed, Miller wrote:

At [the command "Charge"] ... the Army rushed forward, each individual according to the steed of his animal, to within 20 to 50 & an hundred yards of the enemy, some few running up into the very arms of the enemy, & other few persuing those of the enemy who had fled previous to & simultanious with the command to charge. The firing now commenced, but which side fired the first gun is & probably ever will be, a matter of conjecture. Some saying it was on the side of the Mexicans & others that it was on the part of the Texians. At any rate there was a brisk fire kept up on both sides. The contest however was of but short duration. About 10 minutes decided the struggle, on the immediate battle ground. The Texians arms as usual was victorious. The dastardly Mexicans made but a feeble defence. The most of them fired their pieces probably but once. Some few possibly not at all, others had commenced reloading & ramed their cartridges only half down, when the Mexicans threw down their arms & begged for quarters. In about 1 1/2 hours, those who had pursued the flying Mexicans returned, having killed at least three, some say 5; while on the spot were counted 12 dead bodies, making 15 killed on the field, certain, & if we are to credit the assertions of many responsible persons, 17. 82 were taken prisoners, 20 of whom were wounded. 2 of the wounded died on the following night.24 There are among the prisoners 2 capts. & several subalterns.25 The prisoners report their own strength to have been at the commencement of the battle 98 men & subaltern officers, besides 2 Captains, making their total number 100,26 which if true, makes but 1 over the total number of killed & prisoners. This one escaped.27 While on the part of the Texians not the first man was killed or wounded. One or 2 of our horses were wounded & several strayed off. The most of the latter have since been found. There were several Mexican horses killed & several others wounded. The strength of the Texian army at the time of the battle, had they all been together was about 180 rank & file. But some 15 or 20 of them were absent on a spying excursion, & some 2 or 3 had stragled from the main army, leaving the strength of the Texian army at the time of the battle about 160. Of these only about 50 or 60 arrived within gun shot [in] time to fire their rifles before the surrender. ... The battle, one hour previous, was entirely unexpected by the Texians, & probably by the Mexicans. The former acted the part of brave & chivalrous soldiers, batling for liberty & liberal principles, while the latter acted the part of dastardly cowards, reluctantly obeying the mandates of a tyrant, whose highest ambition is despotic power & the suppression of liberty & republicanism. The causes were quite different, & the result such as might have been expected. The Battle was commenced about noon & including the time of the pursuit lasted near 2 hours. The booty taken on this occasion consisted of about 95 mules & horses & as many saddles & bridles, with about the same number of baquets,28 & a quantity of ammunition, made in cartridges; also a number of Spanish spurs, quirts, cartridge boxes, blankets, &c.24Snively reported eighteen killed, eighteen wounded, and sixty-two taken prisoners, making a total ot ninety-eight.—Snively to M. C. Hamilton, June 28, 1843, Army Papers, 1840-1845, Texas State Archives. After the expedition's return to the settled portion of Texas, several of the participants gave newspaper statements in which they mentioned the number involved in the battle. Samuel Huffner wrote: "We broke their ranks, killed 25, wounded 23, and took the rest prisoners."—Morning Star, August 22, 1843 (reprinted in Telegraph and Texas Register, August 23, 1843). T. C. Forbes and Gilbert Ragin reported eighteen killed, eighteen wounded, five of whom died, and a total number of one hundred—Northern Standard, September 14, 1849 (reprinted in Morning Star, October 3, 1843, and in Telegraph and Texas Register, October 4, 1843). The same numbers were given by Moses Wells and others in Northern Standard, September 21, 1843. Hugh F. Young reported that there were seventeen killed and six wounded.—Account of the Snively Expedition signed by Hugh F. Young in Memoirs of John S. Ford (MS., Archives Collection, University of Texas Library), II, 267.25Snively in his report listed: "One Captain; One First Lieut: One Second Lieut.; Four Sergeants; Four Corporals; Eighty-seven privates."—Snively to M. C. Hamilton, June 28, 1843, Army Papers, 1840-1845, Texas State Archives.26All the other reporting participants in the fight agree on this figure with the exception of Snively, who gave ninety-eight as the total number of Mexicans. -Ibid.27Snively (ibid.) is again in disagreement. He reported "not one having escaped." Miller, however, appears to be more nearly correct, because at least one Mexican escaped to take the news of the battle to Governor Manuel Armijo of New Mexico. -The Old Santa Fe Trail (New York, 1897), 96-97. Captain Philip St. George Cooke, heading the American escort on the trail, also had a report on the battle from two Mexicans who escaped.—William E. Connelley (ed.), "A Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XII (1925-1926), 238-240. Moses Wells and others reported that two escaped at the commencement ot the charge.—Northern Standard, September 21, 1843.28Baqueta, the Spanish word for ramrod, was corrupted by the Texans to baquet and generally applied to mean 'gun'.

Although the Mexican soldiers had little of value that the Texans could claim as a prize, Snively kept his prisoners with the command as it fell back to Crooked Creek in order to keep them from spreading an alarm.

Long days of inactivity and reports from the spies indicating no prospect of encountering a caravan in the immediate future brought a feeling of general depression to the Texans. Friction in the command developed, and many of the men wanted to return home. Finally on June 28 the prisoners were released and the battalion dissolved. The mules, saddles, and arms taken from the Mexicans were divided by the Texans who then organized themselves into two groups which Miller designated as the "mountaineers" and the "home boys."

The home boys, about seventy-six in number, selected Eli Chandler, former adjutant of the expedition, as their leader, if indeed he had not already established his leadership by spearheading the opposition to Snively. Instead of heading for Texas, however, Chandler led his followers back toward the Arkansas. It is possible that he was more interested in a separate command than in a return to Texas.

The mountaineers, with Snively in command, also marched to the Arkansas. On the following day, the last of June, Miller, who had remained with Snively in the mountaineer group, wrote:

30th (Friday) To-day a party of our men crossed over on the north side of the Arkansas for the purpose of hunting. They were soon however discovered by the advance guard of the Dragoons of the U.S. under Capt. Cook.29 Our hunters retreated to the right bank of the Arkansas R. where lay the remnant of the army commanded by Jacob Snively, Col. de facto, consisting in all of about 100 men. Capt. Cook commanding about 200 men drew up to the left bank of the River. They then hoisted a white flag which was also done by Col. Snively on the right bank. Capt. Cook now sends over two messengers requesting Col. Snively to appear at his, the Capt's, Quarters, which Col. Snively agreed to do provided that they acknowledge this to be the Republic of Texas soil, and would grant him a passport back to the right bank. To both of these conditions the messenger agreed. After they had parlied on the left bank, Col. Snively was required to surrender up his arms. He was followed back by one or two of the companies of dragoons—say 100 men, 2 pieces of cannon, &c.29Philip St. George Cooke. His account of the encounter is published in Connelley (ed.), "A Journal of the Santa Fe Trail," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XII, 225-234.

Now comes a curious scene. A capt. of about 200 men of the U. S. intruding Himself and soldiers upon Texian soil & there demanding a Texian Col. to surrender up to him our arms excepting only to guns with which he said we might kill game to take us into the settlement in Texas. Upon remonstrating against being stripped of our arms upon our own soil but 5 hundred miles from the settlements, amidst the numerous tribes of Indians who infest these vast regions all of whom are at war with Texas & there being at this time some 3 or 4 thousand Arapahoes, Kioes & [A]paches besides large numbers of Comanches who are daily marauding us & Gov. Armijo who is in this vicinity with a large army. All this the dastard Cook did.

Although several other members of the expedition wrote briet accounts of the capture which were published in newspapers shortly after the Texans returned home and both Snively and Cooke made official reports, the exact point of capture could not be definitely fixed until the incidental bits of topographic information in those accounts could be combined with the Miller day-by-day report. With his diary it is possible to locate the site of the encounter as the Ferguson Grove on the Arkansas River ten miles downstream, east of Dodge City. The question, of course, is whether the Texans were in Texan territory west of the 100th meridian or in United States territory east of that line. The boundary had not been marked, but according to the Melish Map,30 which was specified in the Adams-Oñis Treaty,31 which in turn had been recognized by the United States as the boundary between that nation and the Republic of Texas,32 the Texan encampment at Ferguson Grove was fifty miles west of the 100th meridian33 and therefore that distance within the territory of the Republic. In 18g6, however, the United States Supreme Court held that the boundary lines established by the Adams-Oñis Treaty and specifying the 100th meridian were to be considered as the true 100th meridian and not the meridian as shown on the Melish Map.34 Modern scientific reckoning has established the 100th meridian as passing almost exactly between Ranges 24 and 25 at the eastern environs of present Dodge City, Kansas.35 This means that the Texan camp at the Ferguson Grove was about ten miles east of the true 100th meridian, but certainly Snively in 1843 had every justification for his belief that he was within Texan territory. The Texas claim to that area then was certainly at least as strong as that which the state of Texas later took to the United States Supreme Court in what is known as the Greer County Case.3630Map accompanying Melish, A Geographical Description of the World.31Malloy, Treaties, Conventions,.. between the United States and Other Powers, II, 1653.32Ibid., 1779.33The meridian had not been determined by astronomical reckonings or surveys, but it was almost universally thought to be much farther east than finally determined. Captains Randolph B. Marcy and George B. McClellan in 1858 located the meridian as being almost exactly torty-five miles east of its present determinants. Subsequent surveys were made by John H. Clark, 1850; H. S. Pritchett, 1892; Arthur D. Kidder, 1902; and Samuel S. Gannett, 1929. For detailed accounts of the determination of the 100th meridian, see Thomas Maitland Marshall, The Western Boundary of the Louisiana Purchase (Berkeley, 1914); Philip Coolidge Brooks, Diplomacy and the Borderlands: The Adams-Oñis Treaty of 1819 (Berkeley, 1940); Samuel S. Gannett, Report of the Boundary Commission: Supreme Court of the United States, No. 6 Original Washington, 1929); and J. O. Hicks, "The Hundredth Meridian and the Texas-Oklahoma Boundary in the Panhandle," West Texas Historical Association Year Book, XIV (1938), 106-115.34United States vs. Texas, United States Reports, CLXII (Washington, 1896), 1.35Geologic Map of Kansas, prepared by the State Geological Survey of Kansas, 1937.36United States vs. Texas, United States Reports, CLXII, 1-91. The Greer County Case was settled on a basis of estoppel which would not have applied in 1843. See also Berlin B. Chapman, "The Claim of Texas to Greer County," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, LIII, 19-34, 164-179, 402-421; Webb L. Moore, The Greer County Question (San Marcos, 1939); Charles F. Hartman, The Greer County Boundary Question (M.A. thesis, University of Texas, 1919).

That Cooke was arbitrary and harsh in disarming the Texans, however, can hardly be denied. He had been sent as a protector of the Mexican train, but whether or not his protective jurisdiction and responsibilities extended beyond the boundaries of the United States is another question. Did his safe conduct authority and responsibility extend across Texan and Mexican territory into Santa Fe? Cooke took measures which were calculated to insure the protection of the train even after it passed beyond the claimed jurisdiction of the United States. The Mexican minister in Washington had refused to grant that American troops be allowed to escort the caravans all the way to Santa Fe,37 but Cooke extended to the caravan a security which was almost the equivalent of what Mexico herself had refused to allow. With Mexico and Texas at war and Cooke's government a declared neutral, Cooke proved himself an out-and-out partisan on the Mexican side.37Niles National Register, May 20, 1843.

But for a bit of quick thinking or stratagem on the Texans' part, they would have been left at the mercy of the Plains Indians or the Mexican or American forces. Cooke demanded the Texans' arms, but by and large the guns actually delivered were those which the Texans had captured from the Mexican force in the battle on June 20. The bulk of the Texans' own arms were secreted.38>38The account of T. C. Forbes and Gilbert Ragin in the Northern Standard, September 14, 1843 (reprinted in Morning Star, October 3, 1843, and in Telegraph and Texas Register, October 4, 1843), and that of Moses Wells and others in the Northern Standard, September 28, 1843, both mention the concealment of the guns and the surrender of Mexican arms. The story also was reported in contemporary newspaper accounts in the Telegraph and Texas Register, August 30, 1843, and in the Northern Standard, September 28, 1849, quoting the St. Louis Republican, September 10, 1843. Young wrote: "A good many of our men concealed their rifles, and stacked the escopetas taken from the Mexicans."—Account of the Snively Expedition signed by Hugh F. Young in Memoirs of John S. Ford, II, 272. See also John Henry Brown, History of Texas (2 vols.; St. Louis, 1892-93), II, 289; Hugh H. Young, "Two Texas Patriots," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, XLIV, 16; Grinnell, "Bent's Old Fort and Its Builders," Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 1919-1932, XV, 72-74.

On the morning following the capture, some of the Texans accepted Cooke's offer of an escort back to the United States, but the majority remained with Snively and marched about eight miles to a tributary stream where the mountaineers under Snively joined the so-called home boys under Chandler. The two groups remained together, apparently with a renewed hope of capturing the caravan, but Miller's diary reveals that there was considerable discontent and friction between the two commands. A group of twelve left to join the escort to the United States, but many of the others wanted to return directly to Texas. Miller, totally disgusted with the home boys, wrote:

Though they have undergone the fatigue of a three month's campaign & travelled 500 to 1000 miles for the express purpose of capturing the carryvans, yet now when they are completely within our power & inevitably can be reached in 5 to 6 days, they vote to let them be & quietly proceed home!

On the following day, he reported:

9th July (Sunday) To-day the home party started forward despite of all the persuasions of those who were disposed to pursue the original object of our mission to this country. Previous to their leaving, however, a parade was called & Col. Snively resigned the command of the batalion, in disgust at the want of subordination of men & subalterns, indignantly breaking his sword & thrusting it to the ground.

The Battalion of Invincibles had dwindled to about one hundred men, and before the day of July 10 had run its course the faithful diarist recorded a further reduction, for less than seventy finally remained faithful to the original purpose of the expedition. Unfortunately so much time had elapsed since the Mexican train entered Texan territory that further moves looking toward its capture were probably in the nature of a forlorn hope.

The faithful elected Warfield to command and proceeded down the Santa Fe Trail with the hope of overtaking the Mexican train, which was in all probability considerable distance ahead. By July 12 the Texans reached Wagon Bed Springs on the Cimarron, and on the following day Miller wrote:

13th July (Thursday) This morning at an early hour we were ordered to take up the line of march for the carryvans. When we had proceeded only about 5 miles W. of the Simirone, we saw a trail coming into the Santafee trail on the South side. Our guide ... unhesitatingly gave it as his opinion that this was the trail of 7 to 800 troops under Armijo, with the carryan, whereupon a large majority of our company became panick struck. Col. Warfield wheeled about & said he was going to the settlements in Texas & desired all who would go with him to follow. Whereupon all turned around & started back, not, however, without considerable murmuring from various individuals in the ranks. ... Col. Warfield & various others seemed to be thourly convinced beyond doubt as if by inspiration that Gov. Armijo with an army of 800 men were in attendance on the carryvans and that it would be the highth of folly to attack them. I immediately set all my power of conception to work, and for the life of me could not be convinced from the facts they set before me that any army was with the carryvans except those few who have been with them all the way from Independence. The carryvans seem to have been drawn in two lines about 30 ft. apart. On each side of each of their tracks there is a trodden path such as fifty horsemen marching in Indian or single file would make. And that these were in company with the carryvans, I did not believe. We saw an encampment on the Simirone of several hundred persons supposed to be hunters of whom we had heard a month ago. My opinion is that when we had the fight on the 20th ult. the few who escaped gave these hunters the alarm, who then left & made the trail now supposed to [be] Armijo's with the wagons.39 If it was not the hunters perhaps it was Armijo o army, but not so recent as the passage of the carryvans. Myself & many others were of this latter opinion, & were desirous of continuing the persuit. However, we were overruled by the peremtory command of the Col. Comdt. to follow him to the settlements. So we returned to the simirone river & encamped for the night, 10 mis. Thus ends the great carryvans expedition of the Betalion of "invincibles." E. 10° S.39According to Kit Carson, Miller's conclusions to this point are entirely correct. Edwin L. Sabin, Kit Carson Days, 1809-1868 (2 vols.; New York, 1935), I, 340-347.

The Texans dropped down the Cimarron and the next day, July 14, Warfield resigned, apparently because of the mounting dissatisfaction of the men with his command. Snively was reelected to head the force, but by that time all hope of accomplishing the purpose of the expedition had gone. Following a southeastward course, Snively led the remnants of his command across to the Canadian on July 18. A few days later the Texans encountered the trail which they had made on their way to the Arkansas. They retraced their course across Red River and went on to Bird's Fort, about midway between the present towns of Fort Worth and Dallas, where the expedition was formally disbanded on August 6, 1843.