The Last Treaty of the Republic of Texas1

The Southwestern Historical Quarterly Vol. XXV, No. 3, January, 1922, Author W. P. Webb

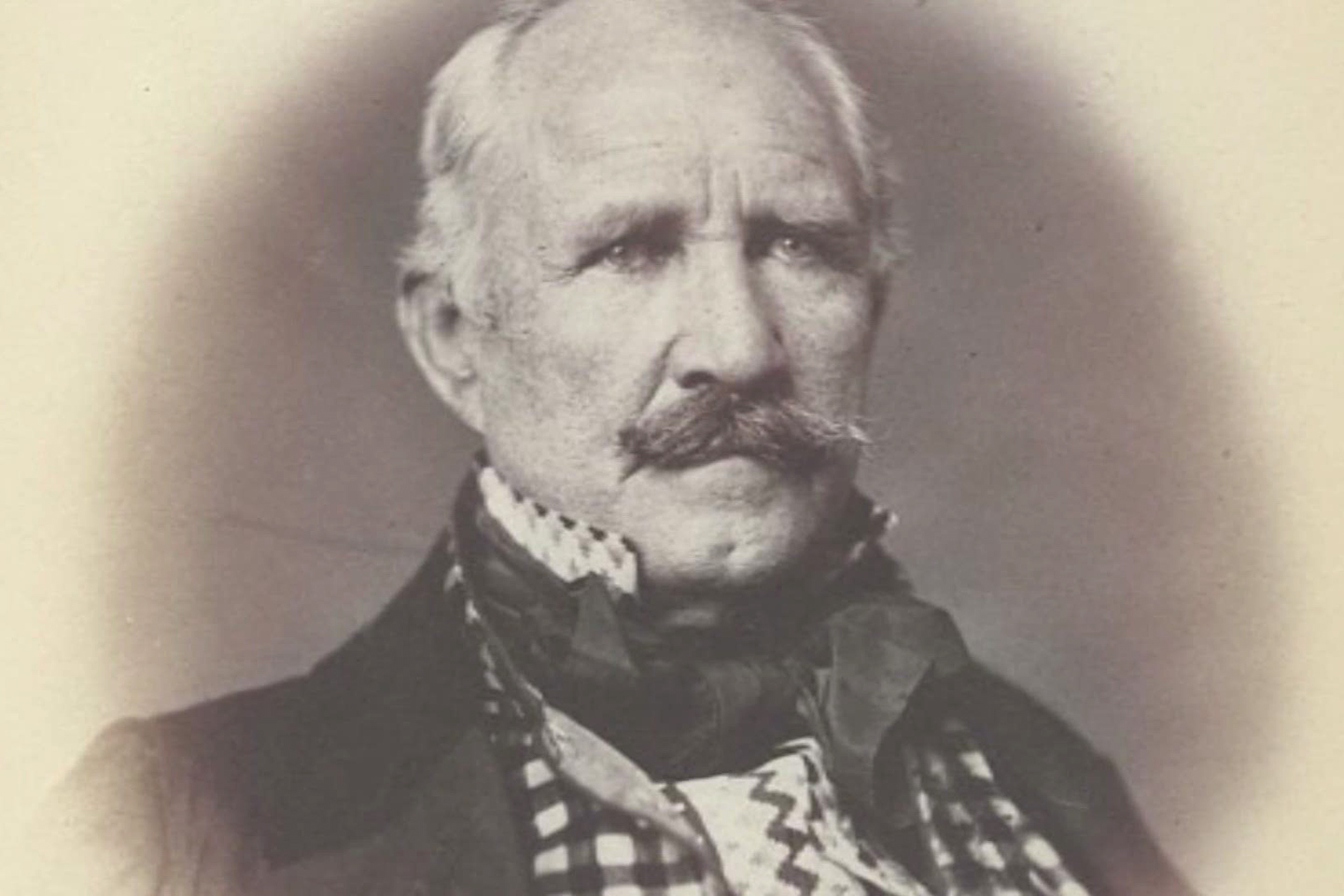

1This study is based on original sources. The documents are to be found in the State Library at Austin, and are entitled "Indian Affairs State Papers." A word about this collection of documents may prove of interest to readers. It consists of several thousand papers, including letters, diaries, reports and treaties, covering Indian affairs in Texas from 1831 to 1860. The documents are in a fairly good state of preservation. Practically all of them are written in long hand (none are typewritten and only a few are printed). In some cases the writing has faded; in many cases it is almost illegible. To read and handle these documents is to feel one's self carried back into the atmosphere and spirit of the Texas border. In the particular period with which this paper deals, certain strong and rugged characters emerge from the frayed manuscript and become real. Such white men as agents Williams and Eldredge, who faced death and wrote about it with delightful unconcern, such Indians as the crafty Delaware guide and interpreter, Jack Harry, or the reliable Waco friend, Ecoquash, or the constant enemy, Pa-ha-yu-ca, chief of the Comanches, these were the men of the frontier. Back of them all, wrapped in the mystery of his own character, dominating and guiding all, stands the sardonic yet kindly old Texan, Sam Houston.The references in the notes are to the collection of documents described above, unless otherwise indicated. The date will serve in each case to locate the particular document. Since many of the Indian names were rarely spelled twice in the same way, I have adopted the spelling which appears to have been most common.

I

The Republic of Texas enjoyed a separate existence from 1836 to 1845, a period of nine years. It was bounded on the north and east by the United States, on the south by the Gulf and Mexico, and on the west by a region practically unknown and inhabited by numerous tribes of wild Indians. During its existence, the Republic was concerned primarily with three great problems: how to get into the United States; how to keep out of the hands of Mexico; and how to handle the Indians. Practically all Texans were agreed upon the proper solution of the first two problems, but there was much difference of opinion in regard to the Indians. The majority of the people doubtless favored the use of military force for the purpose of extermination; but an important and influential minority desired peaceful relationships established through diplomacy and maintained by kindness and fair dealing. This faction was headed by General Sam Houston, president of the Republic for more than half its duration.22The constitution of the Republic (Art. III, Sec. 2) provided that the first president should serve two years, and succeeding ones should serve three. Houston was, therefore, president for five years.

However enigmatical Sam Houston may have been—and he was one of the most puzzling characters in history—his attitude towards the Indians was indisputably that of friendliness and good will. When he came to the presidency for the second time, in 1841, he found the Indian relations exceedingly bad, owing to the policy of force and extermination which had been pursued by President Lamar.3 Houston hated Lamar, and reversed his policy. Hatred, however, was not his sole motive, for he almost loved the Indians, and he sought in every way to regain their friendship which had been lost and to restore their confidence which had been destroyed.3President M. B. Lamar served in the interim between Houston's first and second term as chief executive of the Republic of Texas.

The work of pacification proceeded slowly, and had to be done with utmost patience, for the Indians were suspicious and held back warily like guilty and stubborn children. Houston's plan was to approach them through agents, draw them into councils, establish frontier posts, set up trading houses to supply their wants, and induce them, tribe by tribe, to sign treaties of friendship and amity. His kindly attitude and his procedure are shown clearly in the following letter from one of his agents to Red Bear, chief of the Caddos.

Boggy Depot, July 30, 1842.

To Red Bear,

Caddo Chief: Dear Friend

Your letter dated Grand Prairie in this month was received . . . and I am happy to inform you that two days after the reception of your letter Col. Stroud and others arrived with full power and authority from General Houston President of Texas to negotiate Treaties with your people and all other Indians heretofore hostile to Texas. . . .

The letter further advised the Caddos to separate from the Keechi, Waco, and other Indians unless these could be induced to make peace.4 This letter shows that Houston's plan was to begin with the near and more docile tribes, make peace with them, and then with their help reach out after the more distant and intractable Indians.4R. M. Jones to Red Bear, chief of Caddos, July 30, 1842. On July 5, 1842, Houston appointed four commissioners "to treat with any and all Indians on the frontiers of Texas." These commissioners were Henry E. Scott, Ethan Stroud, Joseph Durst, and Leonard Williams. A copy of their commission is found in the Indian papers under date July 5.

The first two ears of Houston's administration seem to have been spent in such preliminary preparation. All the time the Texas agents were busy cultivating the friendship of the Indians, regaining their confidence, and convincing them that the policy was now one of peace instead of war. By 1813 this preliminary work had been fairly well done, and the government was ready to enter upon the second phase of Indian rapprochement.5 This phase consisted of a series of Indian councils which began in the year 1843, extended through the life of the Republic, and resulted in treaties of peace with practically every Texas tribe. There were four councils, held in September, 1843; October, 1844; September, 1845; and November, 1845. At each council save one a treaty was signed, that of November, 1845, being the last treaty of the Republic of Texas. It was signed some forty days before Texas had completed annexation to the Union. In order to understand this last treaty, it is necessary to consider briefly those treaties and councils which preceded it.5On March 8, 1843, the Texas agents assembled eight Texas tribes on Tahuacarro creek and induced them to sign a truce and to agree to come for a general council in the fall. This truce marks the end of the period of preparation. The United States was represented on this occasion by Pierce M. Butler and Texas by G. W. Terrell, J. S. Black, and T. I. Smith. The truce was signed March 31.

The first general council met at Bird's Fort on the Trinity in 1843. Houston made a strenuous effort to get all the Texas tribes in for this council. In May, nearly five months before it met, he sent the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, J. C. Eldredge, with Delaware guides and two Comanche prisoners, to visit the wild Comanches far out on the northwestern plains for the purpose of inducing them to come in. After many dangerous adventures and hairbreadth escapes, all told about in a careful diary which Eldredge left, the party returned. But Eldredge could not persuade Pa-ha-yu-ca, the Comanche chief, to come in. Chiefs and kinsmen of Pa-ha-yu-ca's band had been killed in the Council House at San Antonio, and the chief said that his warriors were afraid of a repetition of treachery. In fact, it was all the chief could do to restrain his men from taking their revenge at this time. Eldredge, however, did induce Pa-ha-yu-ca to sign a temporary truce in which it was agreed that hostilities and horse stealing should cease until the president could send a commission higher up on the prairies to meet the Comanches. This truce was signed on Red River, probably beyond the present limits of Texas, on August 9, 1843.66A full account of Eldredge's experience on this expedition may be found in his letters and final report in the form of a daily diary. This diary is probably one of the most accurate and interesting documents that we have on Indian life in Texas during the Republic. For another account of Eldredge's expedition see Brown, Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas, p. 93ff. Brown's account seems to be based upon letters of Hamilton P. Bee, who accompanied Eldredge on the expedition.

The next month the Texas commissioners, General G. W. Terrell and E. H. Tarrant, with their assistants, met on the Trinity all the Indians who could be induced to assemble there. On September 29, a treaty was signed with nine tribes: the Delawares, Chickasaws, Wacos, Tahuacarros, Keechies, Anadarkos, Ionis, Biloxis, and Cherokees. The commissioners were not daunted by the fact that some of these tribes were from the United States. Their policy was peace and they were taking all comers. The treaty that was made there may be seen today in the state papers, sealed with the great seal of the Republic set upon white, blue, and green ribbons. It bears the signatures of the commissioners, the marks of the illiterate chiefs, and the bold approval of President Sam Houston.77Treaty of September 29, 1843. This treaty was formally ratified by the Senate on January 31, 1844. Cf. Tom Green, Secretary of Senate, to President Sam Houston, January 31, 1844.

Though the first council, which I have just described, met at Bird's Fort on the Trinity, the three which came after it were held on the Brazos and at a spot so important in frontier and Indian affairs as to deserve particular notice. We find concentrated around one place, near the present site of Waco, all the elements of the two forces which were contending for the soil of Texas. The Texans had built near the mouth of Tahuacarro creek a trading house designed to supply the wants of the Indians, and far and wide over the frontier it was known as Torrey's Trading House. Because a few soldiers were stationed there, it was referred to as Post No. 2 or Trading Post No. 2. Now what was the significance of this trading house and post? What did it stand for? It stood for everything to the east of it. It stood for the white man, the westward-driving, land-hungry Anglo-Saxon. This was his advance, the point of his spear thrust far out into the Indian country. It was a symbol.

Some four miles beyond the Post, where the timber gave way to the prairie, was another symbol, a great Indian council ground, which had served as such long before the white man came. What did it stand for? It stood for everything to the west, for the Indian, and to him it was hallowed ground. It was the intertribal meeting place where the Indians came to hold their councils, to smoke their pipes of peace, to discuss and decide momentous questions. It is quite significant, too, that the white man had planted his outpost on the very edge of the Indian's sacred council ground, notwithstanding the white man came in peace. At the Post and the Council Ground the Texans and the Indians met for trade and for treaty, and at one place or the other the three important councils which I am about to discuss were held.

The second council of the series was to have been held in September, 1844, at the old Council Ground near Torrey's. Owing to numerous delays it did not meet until October, and it turned out to be what was probably the greatest Indian council ever held in the Republic. President Houston was on hand, master of ceremonies and of men, lord of vassals and an emperor of child-like kings. He found himself surrounded by agents and rangers, captains and commissioners, chiefs and warriors, all ready to render him his due of service or homage. The situation was one that appealed mightily to the old Texan's love for pompous ceremonial. In dramatic fashion he created a chief, crowning him with a silken turban set with a pin which looked to the Indian like pure gold.8 To other chiefs he gave gorgeous robes, and to all he distributed gifts with a liberal hand. In the presence of the Great Spirit and the Mother Earth—Indian dieties—a solemn treaty was made which was to bind the white and red men forever. Houston was happy. Had he not reversed the policy of Lamar? Was he not providing what he conceived to be justice for both red and white? On October 9, 1814, the treaty was concluded. It was signed by the authorized agents of Texas (but not by Houston), by the Indian chiefs, and formally sealed with the great star of Texas.9 The original document may be seen now in the archives, the five-pointed seal set upon the white, blue, and green ribbons, each with its special signification: the white denoting peace; the blue, like the sky, unchangeable; the green, like the grass and trees, existing as long as the world stands. Such were the words of Houston. This treaty is one of the few that was ratified by the senate of the Republic.108"His Excellency arose from his seat, and requested Ecoquash to rise also; when he bound around his brow a silk handkerchief with a large pin in the front and proclaimed him chief of the Wacos." Minutes of the Council, October 7, 1844.9The commissioners who signed the treaty were Thos. I. Smith, J. C. Neill, and E. Morehouse. Houston's name does not appear on the treaty at all. Probably the reason that Houston did not sign was that he thought the president should sign the treaty only after its ratification by the senate.10Gammel Laws, II, 1196. The treaty was ratified by the senate January 24, 1845, and was signed by President Anson Jones, who had succeeded Houston, on February 5. I know of but one other Indian treaty to receive formal ratification, and that was the one of 1843. See footnote 7.

So far all was well. Houston had made peace and to him that meant victory, but the victory was not without a blemish. Houston had not been able to induce all the Indians to come in, nor was he sure that the peace he had made would endure. It was hard to keep the path from the tepee to the cabin white. Besides there was much work ahead. The absent tribes, Comanches and Wichitas, must be reached, and the settlement of differences that were sure to arise must be provided for. It was agreed, therefore, that the tribes should assemble each year when the leaves fall to hear the great white chief or his captains, to renew friendship, settle differences and receive gifts.11 And it was the hope of the president to get all the Texas tribes to come to these councils and sign the treaty.11Article 21 of the treaty of October 9, 1844, is as follows: "They further agree and declare that there shall be a general council held once a year, where chiefs from both the whites and the Indians shall attend. At the council presents will be made to the chiefs." Gammel Laws, II, 1194.

The third general council was set for September 15, 1845.12 Long before the day arrived instructions went out to the Indian agents on the frontier to make every effort to bring the tribes in. Houston had been succeeded by his former Secretary of State, Anson Jones, but this change made no difference in the Indian policy. The same agents remained on the frontier pursuing their work as formerly. In spite of their vigorous efforts, it soon became evident to the agents that the task of bringing in all the Indians was too great. Some of the Comanches had gone south to raid in Mexico, and had compelled Benjamin Sloat to accompany them as far as San Antonio to protect them from Jack Hays and his rangers.13 The Keechies still had a prisoner, the Wacos had some horses, while the Wichitas had never consented to treat. In the words of the Indians themselves, "there was still some brush in the road."12By July the date for the council was set definitely, as shown by Benjamin Sloat's letter of July 12.13Sloat's report for July and August, 1845, dated July 12. Sloat died soon after this report was made and was succeeded by Paul Richardson as agent to the Comanches.

The council, set for the 15th, did not meet until the 19th of September, due to the procrastinating Indians and the late arrival of the wagons with presents, and it was not concluded until the last days of the month. The proceedings went on with due formality, speeches were made and presents distributed, but no treaty was signed. There was no reason for a treaty since all the tribes present had signed the one of the previous year.14 The whole affair must have been somewhat disappointing to the government. The tribes most desired—Pa-ha-yu-ca's Comanches, the Wichitas, Wacos, and Tahuacarros—did not appear. However, the government did not give up, and it was soon to be rewarded for its perseverance.14Minutes of the Council of September, 1845.

II

The purpose of the government now was to gather the absent tribes in to a supplementary council at the earliest possible moment. The Comanches under Pa-ha-yu-ca and Santa Anna must be conciliated, the stolen horses must be recovered from the Keechies and Wacos, and the prisoner must be returned to his people. The first intimation of another council is found in a letter dated October 9, 1815, from the Superintendent of Indian Affairs to the commander of the rangers, Colonel T. I. Smith.

His Excellency President Jones] has directed me . . . to meet you if necessary with the Comanche chiefs who were not present in the last Council.1515T. G. Western to T. I. Smith, October 9, 1845.

Ten days passed without any definite assurance of a council. As late as October 21, Superintendent Western gave the Comanche agent the following instructions:

You will proceed to Post No 2 on Brazos and ascertain what or either of them and report to me at this place.1616Western to Paul Richardson, agent to Comanches, October 21, 1815.

This letter shows that the superintendent did not know whether a council would be held. His uncertainty, however, was soon ended. On the day after the above letter was written, he wrote the agent again.

Intelligence has at this moment been received at this office that Pa-ha-yu-ca and his band with some Wichita Tahuacarro, and Keechi Indians are on their way down to meet me in council—you will proceed to the residence of Col. T. I. Smith or to wherever he may be, and act in conjunction with him if necessary . . . in bringing them down to Post No 2 where I will meet you in ten days — you will find both beef and corn at that post.1717Western to Richardson, October 22, 1845. It seems that Col. T. I. Smith wrote to the superintendent giving him the news. On the date of the above quoted letter, the superintendent wrote to Smith as follows: "Your favor of the 15th inst is recd. and I rejoice to find that Pa-ha-yu-ca and his band, with the Keechies, Tahuacarros and Wichitas are on their way in. I will meet you at Tradg house Post No. 2 in ten days. . . . It will be no more than proper that we should assemble there because it is the wish of the Govt. and because we have presents there."

Thus it was settled that the supplementary council would meet, if possible at the old Council Ground, and some time in November. The customary delays ensued. On November 3, the resident agent at Post No. 2 wrote the superintendent of reports that Pa-ha-yu-ca had gone "a long way off" among the mountains, and would probably not return during the whole fall.18 The report must have been based on facts, for the big Comanche chief did not come in.18L. H. Williams to T. G. Western, November 3, 1845. Williams was a resident agent at the post as distinguished from the special tribal, or "field" agents who lived among the Indians. For example, Paul Richardson was at this time agent to the Comanches, succeeding Benjamin Sloat, who had died.

Two special commissioners, Colonel T. I. Smith and the Honorable G. W. Terrell, were appointed to accompany the superintendent and hold the council.19 All were able men, much experienced in Indian Affairs and in sympathy with the policy of the government. Western and Terrell left the capital in the latter part of October and proceeded on horseback to the trading post on Tahuacarro creek. When they arrived there, they found agent Williams and probably a few rangers at the post.20 No Indians were present, but some were reported near. Two Delawares, James Shaw and Jack Harry, were acting as interpreters and messengers between the white and red men. And one may well imagine what an air of suppressed excitement must have accompanied such a diplomatic assemblage. The savages were very deliberate in their movements. It was November 10 before they began to appear at the Council Ground, and when the council was formally called, five days later (November 15), the chiefs of but four tribes were present. These were the Wacos, Tahuacarros, Keechies and Wichitas, accompanied by a number of their warriors and their women and children. All the tribes except the last had already made treaties. Neither Pa-ha-yu-ca. nor Santa Anna with the Comanches were present.19Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council, November 15-16, 1845.20I have followed here the report of Commissioners Terrell and Smith to the Secretary of State.

What is an Indian council like? Much literature of a kind has been produced on the subject, little of which has been done by those with first-hand information. Fortunately there has been preserved very careful minutes of the Texas Indian councils and many letters describing them, and especially is this true of those held from 1841 to 1846. This particular council, or "Big Talk," as it was called in the parlance of the frontier, is described in an exceptional and graphic manner by the minutes and letters, the former containing the talks of the commissioners and the speeches of the Indian chiefs. In fact, the documents are so interesting and so filled with the spirit of the time, that the writer could do no better than incorporate a number of them in this story. What did the white man say to the Indian? What did the Indian reply? No description is so effective as the actual words spoken and written down at the time.

Of the preliminaries of the council we know little. It is probable that the procedure of other councils was more or less duplicated. The chiefs and the white men seated themselves in a circle on the ground, with the Indian warriors and Texas soldiers grouped about them. The peace pipe was passed around the circle and smoked in silence. The stage was set with wild and natural scenery painted in autumnal colors. Above were the slow-moving clouds, presagers of November rain. If there was music, it was that of a running stream or a belated song bird and the noise of wind in the trees.

When the impressive formality of the peace pipe was ended, General G. W. Terrell arose and in solemn voice addressed the Indians:

Brothers Listen!

It is now more than three years since the white man met on this creek to make peace with the Red man.21 When we first met, the path between the White and the Red man was full of brush—it was also Red with the blood both of the White and the Red man—since that time we have removed all the brush and blood, and made the path white between us—it used to be the case that when the White and Red man met on the prairie, they used always to try and take each others scalps, but now when the White and the Red man meet, they sit down and eat Bread and Buffalo meat like brothers. We hope on the part of the white people, that this state of things will always remain,— We have been taught to believe by the Great Father above that the White man and the Red man are all the same people, the same G[rea]t Sp[iri]t has also taught us that it is best for brothers to live together in peace—for this reason the white people of Texas have all this time kept the peace that they first made on this creek with the Red man.22 I would ask any of the chiefs if they have known that the white people have broken the peace that they first made with the Indians—some very bad men that had just come across from the U. S. did kill some Delawares, but as soon as ever we found it out we took them every one, and hung them up on a tree, and that man there (pointing to the agent [Williams]) did it.23 They ought to take that as proof that Texas is determined to keep the treaty made with the Indians. I would ask our Red Brothers if they do not find it is better for them to keep peace and sell their horses and skins to the white man, than to be always at war with him, — it used to be the case that they had no settled home in this country; they were obliged to drive their horses about and carry their women and children with them in cold and rainy weather! Now they can settle down, stay at home, cultivate their corn fields, raise pumpkins and eat them without the fear of being disturbed by any white man. Texas wants to make peace with the Red man, not because she is afraid to make war, it is because we believe it is better for both the Red and the White man, — that is the reason why we prefer to make peace instead of war.21General Terrell evidently refers here to the truce which he had signed with the various tribes on this spot in March, 1843. See footnote 5.22Ibid.23Strange as it may seem, it was really true that the Texans executed some white men for the murder of the Delawares. On October 9, 1844, L. H. Williams made a report to the president of his activity among the Indians. He says: "On the first day after leaving home I received some information of some white men having killed some Delaware Indians . . . in Fannin County. Thinking it best to see what was done with them to enable myself to give satisfaction to the Indians, I proceeded to that place, where I saw Mitchell, Ray, White, and Jones, part of the participants . . . executed on the 17th of that month [July]. None of the Indians were present, which I very much regretted." Williams to Houston, October 9, 1844

General Terrell now turned to the chief of the Wichitas and addressed him as follows:

We are happy to meet all the chiefs here, but particularly him as he is the first of all the Wichita Chiefs that has come down to make peace.24 I would refer to all the chiefs who have been at war with us, if it is not better for them to make peace with us, we would be sure to kill more of his men than he would be to kill ours, we believe that we are all the children of the same Great Spirit and for that reason we ought to be at peace instead of war. We want to teach our Red Brothers to live as we do, by cultivating land and growing corn. We will give the Red man every year corn and hoes to cultivate their ground,—the reason we want them to do this is because we know that the wild game will not always continue. Four years ago, Ecoquash25 knows that there were thousands of Buffaloes all over these prairies and deer in abundance— Where are they now? they have all disappeared. For this reason we want them to make their living as we do, because when the game is gone, they will want something for their women and children to live on—that is all we have to say now, except that we have some complaint to make against some of them.24The Wichita chief was Seatzarwaritz. The Wichitas had never been down to a council, but J. C. Eldredge visited with them when on his expedition to the Comanches in 1843. See his report.25Ecoquash was a Waco, the one whom Houston had crowned chief in 1844. Ecoquash used his best efforts to bring peace between the white and the red men. He accompanied Eldredge on a part of his expedition in 1843 and rendered great service. He held a peculiar position among the Indians. He was something of a spokesman for several bands, but seemed to possess little real authority outside the Waco tribe.

At this point General Terrell registered his complaint against the Indians and undertook to get them to release their prisoner and give up the horses. He continued:

The treaties that we have made with them have been broken by some of them (here the commissioner read articles 5 & 19 of the treaty of [October] 9/44).26 We have given them up all the prisoners that we had except a few Comanches, and these we have been ready and are ready to give up now—we know that the Keechies have one prisoner and that chief there (pointing at the Keechi Chief)27 promised some time since to give him up. We expect him now to bring him in—some of their people have been killing some of our people and stealing some of our horses, out west lately, we do not believe that any of these Chiefs here have committed any of these depredations, they have some bad men among them and we want them to keep them back, or when they steal horses, to take them and bring them to the agent here according to the terms of the treaty I have just read to them.28 There were two white men lately killed on the other side of the Colorado—some say the Comanches did it, others say the Wacos did it, those people on the Colorado and Guadalupe are our People the same as us, and they must not make war on them, more than on us.—29 if they do not restrain their young men from going there to kill and steal we will have to raise men to follow them, and then we may follow them to their country and kill some innocent persons—we have got a great many soldiers come into the country lately—they are all over the country—the soldiers want to go after the Indians, but our Government will not let them, but if they continue to steal horses, they will have to be sent, and they may in recovering the horses kill the men. We have established companies at all the stations on the frontier—if the Red men want to come down, let them come to these companies, and they will be as safe as they are here, but if they steal horses, they must expect these companies to follow them, and perhaps kill them.

I have done!3026Article 5 of Indian Treaty of October, 1844: "They further agree and declare, that the Indians shall no more steal horses or other property from the whites; and if any property should be stolen, or other mischief done by the bad men among any of the tribes, that they will punish those who do so, and restore the property taken to some of the agents."Article 19. "They further agree and declare, that they will mutually surrender and deliver up all the prisoners which they have of the other party for their own prisoners." . . . Gammel Laws, II, 1191ff.27Soatzasoska was the Keechi chief present.28Article 19 of the treaty quoted above.29The Indians did not understand the unity which hound the white people. The Indians looked upon the different settlements as different tribes. Peace with one settlement did not mean peace with all.30Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council, November 15-16, 1845.

An analysis of this speech shows that General Terrell sought four things: to locate the Indians who had committed the murder; to recover stolen horses and prevent further thefts; to encourage the Indians to take up a settled habitat and pursue agriculture as a means of livelihood; and to impress upon them the great military strength of Texas.

General Terrell was followed by the Tahuacarro chief, Keechy-quisoka, who proclaimed his love for the white people and stated that he had already given up all the horses he could find, but promised to look for others, and concluded by asking the commissioners to give him blankets and strouding. When questioned about a war dance which had been held in his village around a white scalp, the chief replied that the scalp was brought there by another tribe, and that he had thrown it away as soon as he found it was a white man's.

"Keechyquisoka is a good man and acted right," remarked the commissioner.

The next speaker was the Wichita chief. His speech is given in full because of its simple and lofty eloquence which puts the rhetorical flourishes of the white man to shame. This is the first speech that a Wichita ever made in a Texas council.

I am a chief— you can stand and look at me and see what sort of man I am. I cannot see the sun,31 but the G[rea]t Sp[iri]t will look down and see me shake hands with my white Brothers. I have a good heart and hand the same as the white mans. I heard of you a long time ago. I was a long ways off, [but] at last I thought I would come and see you. The G[rea]t Sp[iri]t knows my heart and sees my heart cry for what has been done. The white chief looks at me, and I look at them. They are trying to make the path white. I will help them to make it white. I talked with Pa-ha-yu-ca, he loves me and I love him.32 I have listened to what you have said, and have heard nothing but what is good. I have been at war and you see I am a poor man and naked. I think it is best to be at peace.31The reader will recall that the day was cloudy.32Pa-ha-yu-ca was the Comanche chief who had signed the truce with Eldredge. He had not yet come in for a council, but very friendly relations existed between him and the Wichitas, as shown by Eldredge's report. Pa-ha-yu-ca did sign the treaty with the United States agents the following year.

I love all my warriors, but I have got some bad men among them. The white men see me and see that I am a poor man and I want them to consider my situation. I was a long ways off and I tried to stop my men, but could not.

I have now seen you myself and my heart beats for peace. I will go back and tell my warriors what I have seen. The G[rea]t Sp[iri]t hears me, the mother earth hears me and knows that I tell the truth. There is no use to talk too much for men who do so may tell lies.3333Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council, November 15 16, 1845.

The Wichita was followed by the Keechi chief, the one who held the white prisoner. His talk had nothing of special interest and has been omitted. When he had finished, the commissioner asked, "Where is the white prisoner?"

"The reason I did not bring him," replied the Keechi, "was that he had no horse to ride. If you will send the horse I can bring him."

The Waco chief interrupted at this point, saying: "If you will send that man (pointing to Colonel Smith) with his company I will make my men help them get the horses."3434Minutes of the Council, November 15, 1845.

This was the climax. The Indians had agreed to all that was required, and it only remained to be seen how faithfully they would abide by their agreements. It was arranged on the spot to send agent Paul Richardson with ten rangers and the Delaware, Jack Harry, to get the prisoner and horses. Then, in the words of the secretary, "the council adjourned sine die in peace and harmony."35 This was November 15. The following day presents were distributed and the Indians signed the treaty, the last of the Republic. It is a short document, written in a scrawly but legible hand on common paper. It stated that the Indians had heard the treaty of 1844 read and explained, that they understood it, and would accept it as binding.3635Ibid.36Indian treaty, November 15, 1845. For treaty see note 37.

The treaty was signed by the commissioners and by the chiefs and captains of the four tribes present.37 The question which arises now is: Why was a treaty signed here when none had been signed at the council two months earlier? The answer evidently is that this treaty was made for the particular benefit of the Wichita Indians, who had not met the Texans before in council.38 The other three tribes had signed the treaty of 1844 (and also the one of 1813), but were permitted to sign the new one as a matter of frontier courtesy and impartiality.3937The last treaty reads as follows:

Trading Post No 2

Nov 16th 1845

Whereas a treaty of peace, friendship and commerce was concluded at Tahuacarro Creek on the ninth day of October A. D 1844 between the commissioners on the part of the Republic of Texas and certain chiefs and head men of the various tribes of Indians then and there represented—and whereas we the chiefs and head men of the Waco, Tahuacarro, Keechi and Wichita nations having heard the before mentioned treaty read, explained and interpreted to us, so that we fully comprehend and understand the same therefore we agree to adopt, to abide by, and observe the said treaty and all its provisions in the same manner as if we had been present at the making of the same and had signed it at that time and the commissioners on the part of Texas do likewise.

G W Terrell

Commissioners

Thos I Smith

Signed:

Thomas G. Western - Supt Indian Affairs

Keechyquisoka X (his mark) Tahuacarro Chief

Ecoquash X (his mark) Waco Chief

Soatzarwaritz X (his mark) Wichita Chief

Santzasook X (his mark) Keechi Chief

Satzatzkoha X (his mark) Waco Chief

Acowbeda X (his mark) Keechi War Chief

Thitowa X (his mark) Keechi Captain38Annual report of T. G. Western to Secretary of War W. G. Cooke, February 18, 1846.39The Treaty of 1844 (Gammel Laws, II, 1191) shows that the Wacos, Tahuacarros, and Keechies signed the treaty. The names of the chiefs are not in all cases identical with the names given in the last treaty.

To judge by their joint report, the commissioners were well pleased with what had been done. One notes, however, that they failed to call attention to the fact that this was the first treaty that had been made with the Wichitas, nor did they remark upon the absence of Pa-ha-yu-ca and his Comanches.4040Report of Terrell and Smith to Secretary of State E. Allen, November 17, 1845. The two commissioners were probably not familiar enough with Indian affairs to make a comprehensive report. They probably intended to leave that to the superintendent, Thomas G. Western, who was present at the council, but who did not join the commissioners in the report.

Immediately after the break-up of the council, the agent, Paul Richardson, accompanied by ten rangers and Jack Harry, the Delaware, left the Council Ground for the purpose of receiving the Keechi prisoner and the horses which the Indians had promised to give up.41 On December 6, the agent returned to the Post bringing the prisoner and three head of horses.42 The incident is important in showing that the Indians were carrying out their part of the contract. It furnishes some evidence of their good faith.41Minutes of the Council, November 15, 1845.42Williams to Western, December 7, 1845. Jack Harry seems to have been a most obstreperous individual, who was as troublesome as he was indispensable to the whites. He had tried Eldredge sorely on the expedition of 1843, and his conduct was no better on this trip with Richardson. At the Aquilla creek the party stopped to kill game. Jack's mule got away and returned to Torrey's, followed by Jack, badly out of humor. He reported that the party was in disorder and that the agent would not furnish him a mount either to go forward or to return. The truth was that Jack had wanted to borrow agent Richardson's saddle horse, and because his request was denied, the Indian came in and made the unfavorable report. See also Williams to Western, November 23, 1845.

This narrative should end here, and it would but for an episode which followed close upon the treaty. We have seen that the council ended in "peace and harmony" on November 16, and by the end of the following day the Council Ground at Tahuacarro creek was almost deserted. The commissioners and the superintendent had returned to their respective stations, the agent and ten rangers had gone into the Indian country to receive the horses and the prisoner, and the Indians had departed to their villages on the headwaters of the Colorado and other rivers. Only a handful of men remained at the trading post, including L. H. Williams, the agent, a blacksmith named Cogswell, F. E. Eldredge, and four or five rangers.43 This was the situation when a runner arrived and notified Williams that the Comanches under Santa Anna, accompanied by Mo-po-cho-ke-pe, were near and on their way in for a council. This was alarming news, for the Comanches were intractable and belligerent. Here again the original document will tell the story best.43It has been impossible to determine the exact number of white men at the post. "The National Intelligencer" of December 24, 1845, states that seven white men were present. Agent Williams' report indicates that there were perhaps eight. Williams, Eldredge, Cogswell and Perry attended the council, accompanied by Jim Shaw (Delaware). Besides these there were "four or five stationed in the different houses" during the council. This means that there were either eight or nine whites.

Trading House Post No 2

Nov. 23 1845.

T. G. Western, Genl Sup. I. A.

Sir

The morning after your departure the Comanches sent word by express that they had been detained by bad weather but were anxious to meet the commissioners. Immediately upon the receipt of which information I accompanied by Mr. Eldredge rode about five miles to receive them, according to your request, and brought them in. There being a larger party of the Indians than you or the commissioners anticipated I thought that the amount of goods on hand belonging to the Government would no more than satisfy them inasmuch as they had seen the presents you distributed to the other Indians and their actions but too plainly showed that we must please them or they would take the necessary measures to please themselves. . . .

The day after the arrival of the Indians a short council was held and but little said or done except to set apart the following day for trade and the next for the "Big Talk." They traded but little. On the day set apart for the council, seats were prepared and the Indians came up from camp armed with Knives, guns and Bows.44 It was their wish that all the white men present should attend council but I deemed it imprudent, from the hostile appearance of the Comanches, to have them, and thought it best to have four or five stationed in the different houses. Jim Shaw informed them that it was a rather singular proceeding to bring their arms to council; they replied with the rather lame excuse, "That they were afraid they would be stolen if they left them in camp."44This caution on the part of the Comanches is to be explained by the affair at San Antonio known as the Council House Fight, where twelve chiefs were killed by the Texas soldiers. The Council House Fight occurred during Lamar's administration, March 19, 1840.

Every man and woman that were not in council lay under the bluff apparently ready for any emergency and judging from appearances and some remarks which J. S. interpreted I accompanied by Messrs Eldredge Perry and Cogswell went in to council with but little show of getting out of the scrape with safety.

The full proceedings of the council you will find in the report with the exception of Mo-po-cho-ke-pe's asking the young warriors each and singly if they were for peace. Some of them replied that it was a matter of very little consequence whether they were or not as they should abide by the advice of the old men. The Comanches said that we might expect Pa-ha-yu-ca in soon when they could not inform us, and I assure you that if the Gov [ernmen]t does not send us some presents for him or a body of men for our protection there will be difficulty. The last time P. was in he said the White Chief hid, and had it not been for the council of some of the old men there would have been a disturbance. . . .45 I forgot to mention that the Comanches left the morning after they received the presents apparently well satisfied. . . .45I have found no reference in any of the documents, save this, to Pa-ha-yu-ca's visit to Post No. 2. He evidently came unexpectedly and at a time when the Texans were unprepared to entertain him.

The whites located here seem to think that should they be similarly situated again they would like the Georgia Major be troubled with a slight lameness, and retreat before the enemy appear.

With assurances of the most distinguished consideration I remain

Your Obt Servt.

L. H. Williams

Pr F. E. Eldredge

After the council had broken up, the agent distributed all the presents he had, a complete list of which was attached to the account of the proceedings. This list is typical of what was usually given on such occasions. It contains such articles as silk and cotton handkerchiefs, blue and red strouding for breech clouts, blue and red drill, shawls, brass wire, files, needles, looking glasses, tin buckets, tin pans and cups, fine combs (a favorite article with the Indians), tacks, thread, vermilion, indigo, verdigris, squaw hatchets, unbleached domestic, red and white blankets, fire steels, and gun powder.4646The following is the list of presents distributed to the Comanches on this occasion:

21 silk handkerchiefs

3 cotton handkerchiefs

4 cotton shawls

8 pieces blue print

404 yards blue and red strouding

73 pieces blue drill

75 Ibs brass wire

4 3-12 doz. tin pans

13 tin buckets

12 lbs vermilion

10 doz cinch butcher knives

1 1/2 doz cocoa handles [?]

5 doz horn combs

7 8-12 doz ivory combs

2 4-12 doz files

7 1/2 M brass tacks

2 lbs linen thread

1 1-12 doz fire steels

1 1/2 M needles

1 1/2 doz looking glasses

4 1/2 lbs indigo and verdigris

2 1/2 doz squaw hatchets

4 doz tin cups

1 1/2 pr red blankets

7 1/2 pr white blankets

42 small bars lead

19 large bars lead

2 pieces unbleached domestic, 44 yds

35 Ibs powder

III

With the distribution of the presents to the Comanches, the Indian relations of the Republic of Texas were brought to an end. This council was the last, and if one is to appraise the policy of the Republic, he must make that appraisal here. All the evidence is in. Furthermore, the future relationship of Texas with the Indians was, or would soon be determined, as I shall show directly. From what has been said, it is quite evident that the policy of peace had been tried earnestly for four years, and there is some evidence that the policy was a success.

In the first place, the government of Texas had succeeded in drawing the Indians into a series of councils which have been briefly described. It had, during these councils, made peace, by treaty or truce, with every important tribe in the state.47 In the second place, these treaties had been fairly well observed, and they remained in force until the end of the Republic. It has been asserted by some that the Indians did not keep their treaties, and it is true that there were infractions of the peace and occasional raids. But on getting down to cases, we find these occurrences to have been comparatively rare. The truth is that much noise was made in those days over every Indian incursion and over every horse theft and what not. My purpose is not to condone the Indian or even to sympathize with him, but it is to arrive at the facts in order to set a value upon the policy which produced them. It is pertinent to ask how the murders committed by Indians would compare with those perpetrated by white men within the settlements; or how the theft of horses then, granting that all horses that disappeared were stolen by the Indians—a liberal concession—would compare with the theft of automobiles today. These comparisons cannot be made with the data in hand, but a consideration of them will give pause to extremists. It is a fact, and must be admitted, that the Indians had carried out the terms of their treaties to the extent of giving up their prisoners and their stolen horses. The brush was being cleared from the road and the path from the cabin to the wigwam was whiter than it had been for fifty moons.48 Evidence of this is found in the last annual report of the superintendent of Indian affairs. The report gives such an excellent and interesting summary of the situation that I give it in full.47The Apache Indians occupied the trans-Pecos region and did not come much in contact with the Texans. No effort was made, so far as the evidence shows, to reach them.48By a "moon" the Indian meant all four phases of the moon, or 28 days.

Hon. W. G. Cooke Sec. War & Marine

Sir

In relation to Indian affairs, I have briefly to say that nothing material has occurred since my last annual report.

The Indians in general have manifested the best disposition to maintain inviolate the treaties made with them and to meet us in peace and friendship.

The Comanches upon our invitation met us in Council September last, appropriate talks and interchange of civilities passed between the parties presents were made them to the extent of their wishes, and gratified with their reception, they returned to the Prairies.49 The various Tribes of minor consideration also attended the assemblage and joined in a renewal of their protestations of friendship.49The Comanche, Mo-po-cho-ke-pe, had been present at some council, but he was not in Pa-ha-yu-ca's band.

In November last a Council was held with a Wichita chief accompanied by the Wacos, Tahuacarros, and Keechies. I am much gratified to state that we succeeded in making a treaty with them, the Wichitas heretofore never having consented to treat with us. The Treaty alluded to is already on file in the War Department and conforms to the treaties made with other tribes.

It must be a source of congratulation that during the past year as well as at the close of our separate existence, we have been and are at peace with all men both red and white.5050The Mexican war began two months after this letter was written, April, 1846.

Convinced that the good effects of the Indian policy pursued by the late administration of the Republic for the past four years, have become the more evident, as the more tested, I have the honor to repeat the assurance of distinguished consideration with which I remain

Your most obedient and faithful servant

Thos. G. Western Supt Indian Affairs51

Indian Bureau

Austin, Feby 18th 184651In evaluating this letter, it should be borne in mind that it was written after Texas was safely in the Union. The Indian policy was in the hands of the United States, and the superintendent was not bidding for preferment by making such a report.

The fruit of the tree which Houston had planted and nourished so carefully is found in the sentence: "It must be a source of congratulation that during the past year as well as at the close of our national existence, we have been at peace with all men both red and white."

Peace in Texas! Strange phenomenon! For nine years Texas had been free, but never before had she known actual peace.5252When Mexico saw that Texas was about to enter the Union, she made flattering offers of peace. Until this time she had maintained a state of war.

Then came annexation, completed about five weeks after the Indian council just described and accompanied by swift and mighty changes, not physical or visible, but silent and intangible. These were changes in relationships. Texas had solved her three great problems: she had entered the Union; in so doing, she had escaped all fear of and danger from Mexico; and she had received a guarantee of protection from the Indians.53 But how had the Indians themselves fared?53Annexation was completed December 29, 1845. Wooten (editor), A Comprehensive History of Texas, I, Part II, 684. The guarantee of protection from the Indians came to be looked upon by Texans as theoretical.

In entering the Union, Texas reserved to herself all her public land, which, of course, included that inhabited by the Indians.54 But she assumed no responsibility for the Indians, a fact which had great significance. Moreover, Texas gave up to the federal government the right, and the duty, of defense, which meant frontier protection. Pursuing the thought to its logical conclusion, we see that Uncle Sam would have to remove the Indians from the land as rapidly as the Texans were ready to occupy it. This explains why there are no Indians or Indian reservations in Texas today. Before annexation the Indians had an implied right to occupy Texas soil. At least Texas had no right to drive them to any foreign soil, either across the Rio Grande to Mexico or across Red River to the United States. Texas must kill the Indian, or let him live, somewhere, somehow. With annexation, the land, and the implied right, was lost to the Indian. The red man had become a charge upon Uncle Sam, an interloper in his native home, and an intruder in the house which once had been entirely his own. Texas, the Republic, had an Indian policy—with Houston it was peace, with Lamar it was war, in either case a policy; but Texas, the state, had none. The alternative was gone. There could be no peace; there must be war. The Indian had to go.54Joint Resolution of Annexation, Gammel Laws, II, 1228f.

The case of the Indian, however, was not entirely desperate, for he had gained a friend, real or potential, in Uncle Sam, who could still pursue a policy. If the policy was war, Texas would co-operate; if it was peace, Texas would become rancorous and critical. Few have understood, or called attention to, this peculiar shifting of relationship which took place with annexation. Bearing what I have said in mind, one can understand why friction arose, and was bound to arise, between the federal government and Texas over the Indian question. The federal government was inclined to benevolence towards the Indians, and desired only to keep them back from the settlements; the Texans wanted them removed or exterminated. And this serves to explain why the Texans soon substituted rangers in the place of federal soldiers on the frontier. The rangers were Indian exterminators; the soldiers were only guards.

This swift and silent realignment of forces meant little to the Indian. Such subtlety was not for his mind; his cunning was of a different sort. Had not the Great White Chief given him the paper? Had not all agreed to live in peace? The Indian did not know how quickly brush can grow in the road which the white man has made and called clean. But as the warmth remains after the fire is dead, so did the friendship of the Indian continue after the policy which had engendered it had been reversed. The proof of this statement is found in two facts: (1) The Texas frontier enjoyed comparative peace from the time of annexation until near 1850, due as much, no doubt, to the relationship established by the Republic as to the presence of a few clumsy dragoons on the border. (2) The federal government was able to conclude, almost immediately, a treaty with all Texas tribes. The agents arrived at Post No. 2 in February, 1816.55 Within three months the treaty was made and signed at the old Council Ground on Tahuacarro creek.56 One cannot well believe that this quick and effective work was due to the superior ability and skill of the United States agents; it was due more to the effective work which had been done in preparation by Sam Houston and Superintendent Thomas G. Western and the corps of faithful agents and workers under their command.55Williams to Western, February 21, 1846. Williams was doubtful as to how he should receive these commissioners.56U. S. Indian Treaty, May 15, 1846. The U. S. treaty was made between P. M. Butler and M. G. Lewis and 63 Indians, including chiefs of the Comanches, Wacos, Keechies, Tonkoways, Wichitas, and Tahuacarros. It was amended and ratified by the U. S. senate February 15, 1847, and signed by President Polk March 8, 1847.

Here ends the story of the last treaty. Coming as it did in the twilight zone when Texas was losing her identity as a nation to become a state, it has escaped so far the attention of the historian. It marks the end of a policy and the birth of an attitude towards the Indians. It affords a vantage point from which to survey the Indian affairs of the Republic. From the same point one can see the destiny and the doom of the Texas Indians.