Surveyor Warren A. Ferris at the Three Forks

Excerpt from the book Land is the Cry! by Susanne Starling, 1998

One day in 1982, Eastfield Community College professor Susanne Starling discovered a historian’s gold mine in one of her history classes.

During a discussion of early Dallas settlers, a student named Greg Smith suddenly spoke up with an interesting claim: one of his ancestors, he said, was the original surveyor of what is now Dallas County, and that ancestor’s name was William Angus Ferris.

Starling had never heard of Ferris, but when her student brought family documents to class, she couldn’t believe her eyes. William Angus Ferris had been a prolific writer, and his diary and drawings showed that before settling in Texas, he had been a fur trapper and mountain man in Yellowstone. The extensive journal he kept told of life in the West in the 1830s. He also gave the first public description of the incredible geysers found in what is now Yellowstone National Park.

Fascinated by the information the documents showed, Starling began to research the life of Warren Ferris. What she found led her to spend 10 years working on her book, Land Is the Cry! The Life of Warren Angus Ferris, Pioneer Texas Surveyor, eventually published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Ferris originally came from Buffalo in western New York state, which at that time was itself still a frontier. After six years in the West, he followed his brother Charles to Texas shortly after the Texas Revolution in search of land for homesteading.

Shortly after his arrival he was hired as the official surveyor for Nacogdoches County, which then included much of northeast Texas, including what is now Dallas. Warren Ferris surveyed the area beginning in 1839 – well before the better-known “founder” of Dallas, John Neely Bryan, showed up.

“At the time Ferris surveyed the Three Forks area of the Trinity River, there were plans to build a town there and name it Warwick. Because of a drought, those plans fell through, otherwise, we’d all be living in Warwick, Texas,” says Starling, laughing.

Ferris is also credited with the unusual layout of Dallas streets, which has affected the directions in which Dallas has grown.

“In the early days,” Starling explains, “access to water was of primary importance. Because of that, plots were surveyed in the directions the streams and creeks ran–at an angle southeast to northwest.”

Starling, herself a native Texan, grew up in Dallas and Greenville and holds degrees from Baylor and the University of North Texas. She taught history at Bryan Adams High School in East Dallas from 1961-67, and then in the Dallas County Community College system until she retired to travel and write.

At the time she “discovered” Warren Angus Ferris, she had become a true urban pioneer, having purchased and renovated a home in Old East Dallas in the 1970s. “I had studied urban history at North Texas and I really felt like I was doing something no one had ever done before.” Her research on Ferris and the early settlement of the area seemed to dovetail nicely with her background and personal interests.

Warren Angus Ferris lived his life out in North Texas, fathering 12 children before his death in 1873. Today, a Texas Historical Marker can be seen at the site of his 640-acre homestead near Garland Road and St. Francis Drive in the Forest Hills section of East Dallas.

The cemetery where he rests, however, was bulldozed and paved over some years ago–an ignominious end for the man esteemed local historian A.C. Greene calls “the most unappreciated figure in Dallas history.”

This book excerpt includes popup citations. To read a citation, simply click on a citation number.

"Jack of Diamonds"

WHEN THE TEXAS CONGRESS convened in the fall of 1837, Sen. Isaac Watts Burton of Nacogdoches was positioned to advance associates like Warren Ferris. The Second Congress of the Republic of Texas met in Houston City, a new town promoted by the Allen brothers near the site of old Harrisburg. All was "bustle and animation" and a "spirit of speculation" in the seat of government where people were thrown together from all over the world.a1 In mid-December, the Texas Congress elected officials to administer the affairs of the Republic in its various subdivisions or counties.a2 Senator Burton nominated Warren A. Ferris as official surveyor of Nacogdoches County, a far-flung area that included much of northeast and north central Texas. Ferris held this potentially lucrative post for nearly three years, until he became deputy surveyor in late 1840.

The same Congress provided for a land office to open in Houston early in 1838. Upon being notified of his appointment, Ferris took his oath of office,a3 made bond in the amount of $10,000,a4 selected his deputy surveyors, and eagerly awaited instructions. In the interim, he managed Burton's pro-Lamar newspaper, the Texas Chronicle, a job that he held until August when the press was sold and moved to San Augustine.a5

Ferris related his situation in Nacogdoches and his preparation for surveying:

I came to Nacogdoches in '37 had no acquaintance and no money. Charles' friend Burton assisted me I conducted his press until it was disposed of and through his influence was elected County Surveyor by joint vote of Congress. When I came here I was perfectly rusty in surveying and laying 6 weeks sick I got Gibson's surveying and completely mastered it and after receiving the appointment instructed my Deputies and by this means mastered Gummers, Flint, Davis & c. at which time with my previous knowledge of mathematicks I was an accomplished surveyor.a6

In truth, Ferris was as qualified as most pioneers who claimed to be surveyors. His grounding in mathematics allowed him to determine variations of the compass. Many self-taught frontier surveyors, apparently incapable of the calculations, felt it unnecessary to establish "true north" as it varied from place to place. After his experience in the Rocky Mountains, Ferris had a good sense of distance and direction; and, judging from his map of the fur country, he was a skilled draftsman. Surveying required very little equipment, only a "peep-sight" compass, a "Jacob-staff"'" for mounting the compass, and chains which were regulated to the length of ten varas or 27 feet, 9-1/2 inches.a7 With a bit of knowledge, minimal equipment, and a great deal of self-confidence, Warren Ferris deemed himself ready to enter the surveying business.

After the Texas General Land Office opened in January, Land Commissioner John P. Borden instructed surveyors to establish county boundaries, map the county, then locate lands to be distributed to veterans and new immigrants. The central duty of the county surveyor was to create an up-to-date map of each county, showing the old surveys and connecting them to new ones without gaps between the two. Mapping Nacogdoches County involved listing original claimants and the quantity of each claim. Much confusion arose from interpreting boundaries of Spanish and Mexican grants dating back to the 1790s. In the clamor to secure title to new lands, conflicts with older grants were inevitable. Surveyors often were guided by inaccurate, incomplete maps and even more ambiguous instructions. Commissioner Borden noted "the vague manner in which the acts defining the boundries [sic] of the several counties are expressed" and urged cooperation with authorities in adjoining counties in order to reach "some mutual agreement about boundries." Borden directed: "You will proceed as soon as practicable to cause the lines of your county to be run." Ferris was then to furnish surveyors of neighboring counties with maps showing the "true situation."a8

Difficulties were compounded by the existence of the Cherokee Reserve, claimed by the Cherokee Nation and guaranteed to them by the still unratified treaty of 1836. This choice strip of land, 130 miles long by 60 miles wide, included what is now Smith, Cherokee, Rusk, and Van Zandt Counties. Its rolling, pine-filled hills and sandy, well-watered soil was much coveted by Anglos in East Texas. But Borden cautioned Ferris: "You will be particular not to allow surveys made for individuals on lands within the limits specially reserved by the Government for the Cherokees and other friendly Indians."a9

Texas land laws reflected transition from Spanish/Mexican land practice to that of Anglo/Southern United States with attendant confusion. Under Mexico, distances were measured by the Spanish league and vara, while grants were made in the "labor," land with water for farming, and the much larger "league," suitable for grazing. Immigrant farmers quickly seized on the idea of becoming stockmen, requesting the "league and labor," which became the standard grant. In 1838, moving to more common English measurements, Borden arbitrarily ruled that a Vara would measure 33½ inches, a Labor (one million square varas) would be 177.1 acres, and a League (25 million square varas) would measure 4,428.4 acres.a10

Alongside the old Mexican system was now introduced the Anglo-American headright grant which gave each head of family a section of 640 acres, with lesser acreage for single men and widows. Land was Texas's major asset; on its speedy survey and development rested the future of the infant Republic. The Texas Congress, however, could not quite decide whether it wished to sell its public domain to raise money and pay its debts or whether it wished to attract settlers by giving land away. In this setting of ambiguous directives, conflicting laws, and competing claims, Warren Ferris began his surveying career.

The new Texas land laws required that a prospective claimant, on receiving his certificate, engage a surveyor to locate land in an unclaimed area and survey it. A fee amounting to one-third the value of the land was paid for a surveyor's field notes,a11 which were then approved by the offcial county surveyor, presented to the county land boarda12 for approval, and finally sent to the General Land Office where a patent or deed would be issued. Years might elapse between granting a certificate and issuing its title. County surveyors and land commissioners held tremendous power in the process.

Although many early Texians were "practical" surveyors, guidebooks advised immigrants to use official surveyors if they wished to validate their claims, so Ferris's business was lively. In the spring of 1838, he divided Nacogdoches County and dispatched his deputies to survey on the Angelina, the Sabine, and Neches Rivers where rich "bottom" land was in great demand.a13 If possible, each block of land was fronted on a stream and then run back for quantity.

Surveyors' guidelines were vague; they were merely told to locate certificates on "unappropriated" land. Typical were Ferris's instructions to deputy Absalom Gibson on February 24, 1838. Expressing confidence in Gibson's ability, Ferris instructed him to determine the boundaries of his territory, note the kinds of timber on the land, and list the names of his chainbearers or assistants. Gibson was told to use a compass of the Rittenhouse construction, to utilize pins of a certain size, and to mark trees with a cross.a14 The Land Office provided a standardized form for field notes.

The main impact of Texas land law was speculation. Because neither veterans of the Texas Revolution who claimed bounty and donation land nor new immigrants claiming headrights were required to live on the land, a brisk trade developed in the sale of certificates and field notes. Speculators hovered like vultures, eager to purchase landscrip (paper redeemable in land) and put together huge tracts for resale. Forgery and fraud were rampant. Land boards, which had to rule on the validity of claims, were swamped with applicants; in two years, 38,000 applicants asked for over fifty million acres of the public domain.a15 Because he questioned their legality, President Houston refused during 1838 to sign many of the patents,a16 an action that drove up the value of the certified copies of field notes.

Warren Ferris reported his good fortune and revealed his personal priorities in a high-spirited letter to his brother Charles. Taking advantage of the rampant "certified copy" fever, he had been getting double fees for his field notes, making $10 to $25 a day. His debts were partially paid, his credit good in any Nacogdoches store, and 100 completed field notes in his desk would bring him $400 at any time he chose. Although as county surveyor Ferris was not allowed to speculate in lands, he placed land near Nacogdoches in his brother's name. A recurrent fever delayed his surveying for two weeks, but Warren Ferris assured Charles, "I am certainly in a situation to coin money and shall not neglect the opportunity."a17

Both brothers could file for headrights when Charles Ferris returned to Texas; but, in order to get his due, Charles would need to find two witnesses to swear he came to Texas prior to independence.a18 Warren doubted Charles would get all he expected. Speaking of the huge Nacogdoches County area, Warren Ferris reported, "There has been much fraud practised [sic] . .. and hundreds of fraudulent certificates issued . .. a good portion of the public domain will fall into the hands of swindlers." Still, he judged that Texas would not be much harmed as, "Land will rise rapidly in Value and the more owners there are to the Soil the more easily will the National debt be paid by the people."a19

Warren Ferris urged his family to write all the news from Buffalo and immodestly gave them permission to tell everyone of the importance he had achieved. "I like for some folks to have reason to be envious," he admitted. He concluded his optimistic July 1838 letter with a jaunty signature—"Jack of Diamonds."a20

His status as county surveyor earned Ferris admission into Nacogdoches society, where he was seen as a responsible and able young man. He was welcomed in the homes of Nacogdoches leaders such as Adolphus Sterne and Martin Lacy. In May 1838, Ferris was named administrator of the estate of Horace Chamberlain who died at Galveston in February while serving in the Texas Armya21 In August 1838, Ferris was selected to assist Mary Harris, widow of Dr. E. G. Harris, in the administration of his estate.a22 Ultimate recognition that W. A. Ferris was a "comer" in Nacogdoches was his initiation into the Milam Chapter of the Masonic Lodge.a23

At the height of his prosperity in 1838, Ferris purchased land from Martin Lacy and, in preparation for his family's coming from Buffalo, planned to have a house built. Sarah Lovejoy gave a description of the Ferris "home to be" in a letter to her brother Joshua. The house was sited on a 750-acre tract some thirty-five miles west of Nacogdoches. Part prairie and part forest, the land had plenty of black walnut trees, a good mill stream which ran most of the year, and an excellent spring of water near the buildings. Sarah described a "dogtrot" or double cabin house with separate kitchen; two cabins, each sixteen by twenty feet, joined by an eight-foot-wide "Texas hall," porches on the north and south ten feet wide, the whole covered by substantial roof, and windows without sashes.a24

Ferris's new-found prosperity was in direct contrast to the situation in western New York, hard hit by the Panic of 1837. Before the Ferris/Lovejoy family could liquidate its holdings to join him in Texas, the economic depression worsened. They found themselves "land poor," barely able to pay taxes, and trapped in Buffalo.a25 Charles Ferris marked time studying law and writing for the Buffalonian, while Ferris's young half-brother, Joshua Lovejoy, returned to Michigan to wait tables and tend bar. Lovejoy complained of chapped hands too long in dishwater and bemoaned the climate so bad for consumption.a26 His lodge, the "Staff Union Fear Naughts," was involved in the campaign to liberate Canada, a movement in support of William L. MacKenzie and the so-called "Patriot rising" or Upper Canada Rebellion of 1838.a27

A lengthy letter of May 30, 1839, from Charles Ferris to Warren in Texas fully described the Buffalo situation:

Times have been so hard here for the last two years that it has been almost impossible to get along, and I have had during that time to support a large family, pay taxes to a considerable amount on the land, and arrange a settlement with Henry which thank Heaven is now nearly concluded.a28

Charles detailed the terms of settlement whereby Henry Lovejoy received two-fifths of the disputed property for agreeing to pay outstanding court costs and getting their uncle to release the mortgage. He estimated that his mother and sisters would then have clear title to land worth about $30,000 which, if it could be sold, would make them not rich, but independent.

Of the rest of the family, Ferris reported that Joshua at age twenty-three had done himself and his family no good; he was "some five or six hundred dollars in debt in Michigan for the Lord knows what." Sarah, age twenty-one, was "of a literary turn of mind, somewhat talented I think not handsome and almost a recluse from society." Ferris felt, "I think I must bring Sarah [to Texas]. . .. Her health is not good. ... The climate of that country will suit her to a t." Fifteen-year-old Louisa, "pretty, full of spirits, witty and satirical," seemed born for a social life; "She could queen it nobly in Texas," he judged. Charles Ferris proudly described his two sons. His namesake Charley, a "beauty and a wit," was three years old; infant Ned, four months old, was, according to his father, a lively, good-natured youngster.

After news of the family, Ferris ended the long, rambling letter by inquiring as to whether Warren had received a trunk of books and clothes or the newspapers sent from Buffalo by way of O. H. Willis. Finally he implored his brother to go to Natchitoches in person to sign essential legal papers agreeing to the settlement with Henry Lovejoy. "I am anxious to join you there . .. my forced stay here till I get returns from you is the only thing that very much troubles your Brother," Charles Ferris concluded.a29

Meanwhile, rumors rocked Texas of renewed war with Mexico, possible conflict with the Mexicans in Texas, Indian raids, or any combination of the three. Neither Texas nor Mexico was ready to end hostilities. Fearing reinvasion, some Texans again called for a preemptive strike against Mexico. The lingering fear of collusion between nearby Indians and disgruntled local Mexicans nagged at East Texans especially. Rumors persisted that Mexican agents were moving among the tribes. Most Anglo-Americans viewed Indians with suspicion and regarded Mexicans as an inferior, mongrel race. For their part, Mexican citizens saw their property seized and their rights denied while Indian tribesmen were alarmed by the advance of white surveyors and settlers into their traditional hunting grounds. Mutual distrust might easily erupt into violence.

During this crisis period, the government of Texas was locked in a destructive power struggle. President Sam Houston, determined to pursue a policy of frugality and orderly development, was at odds with the Texas Congress. Sen. Isaac Burton, aligned with Vice President Mirabeau B. Lamar, was ringleader of the clique that opposed Houston. Lamar and his followers wanted expansion, even if it meant extermination of the Indians or confrontation with Mexicoa30

Houston vetoed the Land Bill in 1837, hoping to delay surveying until ratification of his treaty with the Cherokees could protect Indian land. Burton, chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs, questioned Cherokee loyalty. He asserted that the Cherokees, with "elevated views of their own importance," planned to unify Indian resistance against the Republic. On October 12, 1837, his committee reported against the treaty and on December 16, the Senate nullified it.a31 Early in 1838, Houston vetoed Burton's bill "to provide for the protection of the frontier," but Congress passed the Defense Bill, as it had the Land Bill, over Houston's veto.a32 Providing for a volunteer militia, paid directly by Congress, the act allowed the military under the command of General Rusk to operate independent of the executive during the summer and fall of 1838.

The so-called "Mexican Rebellion" erupted outside Nacogdoches on August 4, 1838, when Texans attempted to recover "stolen" horses from a nearby Mexican rancho. Shots were fired, and one Texian was killed. A respected Mexican citizen of Nacogdoches, former alcalde Vicente Cordova, organized the Mexicans to defend their rights. Subsequently it was alleged that Cordova had been in contact with Mexican authorities in Matamoros as early as February 1838, that he styled himself "Commander of Mexican Forces in Texas," and that he had attended a council with the Cherokees and Mexican agents in July 1838.a33 Although he was not privy to this troubling information at the time, General Rusk did not hesitate to call out the Nacogdoches militia. On August 7, Rusk learned that Cordova was camped on the Angelina River with a large number of armed followers, including Indians. Houston, who was visiting in Nacogdoches, issued a proclamation calling for dispersal of the Mexican malcontents. Cordova replied:

The citizens of Nacogdoches, being tired of the unjust treatment and the usurpation of their rights, cannot do less than state that they are embodied, with arms in their hands, to sustain those rights and those of the nation [Mexico] to which they belong.a34

Cordova emphasized that his people were determined to defend their rights at the cost of their lives, if necessary; he promised not to bother Anglo families in return for the same promises of good faith from General Rusk. Rusk would deliver no guarantees. Instead, on August 10, he issued an inflammatory denunciation of the "contemptible enemy" who had taken up arms threatening Anglo-American "homes, firesides and liberty." Rusk charged that the "cowards and traitors" compounded their perfidy when they "held illicit commerce with worthless savages." Rusk urged the women and children of Nacogdoches to remain in their homes and trust their safety to those of "stout hearts and strong arms" who would defend them. He called upon the men of the Third Brigade to shoulder arms and "exterminate" the "worthless renegades."a35

Without further violence, Cordova moved his camp into the Cherokee Reserve; then, when the Cherokees refused to harbor them, Cordova's band traveled farther west to Kickapootown near present Frankston in Anderson County. Although Houston ordered Rusk not to enter the Cherokee Reserve, the Nacogdoches militia advanced to the Indian village at Kickapootown where on a misty October morning they made a surprise attack, destroying the camp and taking prisoners who were later brought to trial at San Augustine.a36 Cordova escaped with a remnant of his men and was next reported to be camped near a Keechi Village at the Three Forks of the Trinity (present Dallas County). An Indian trader characterized their gathering as a "Grand Council of Renegades." About 1,000 Indians of many tribes were said to be powwowing during November 1838 to discuss what could be done about white aggression.a37

Both Warren Ferris and his patron Isaac Burton enlisted in military service during the Cordova Rebellion, which Burton anticipated as a "fine hanging frolic."a38 During the August excitement, Ferris was a sergeant in the Nacogdoches militia; and, in the expedition against Kickapootown that fall, he was a private in a company of Nacogdoches mounted volunteers.a39 Knowledge of the land made Ferris and his deputy surveyors invaluable to such military expeditions. Indeed, it was often the surveyors who first reported Indian movements on the frontier.

At Kickapootown, Ferris observed General Rusk using his favorite military strategy, luring the enemy from cover with taunts. Rusk hurled insults at the Mexican/Indian camp: "you damned cowardly _____ _____ _____, _______________ come out and show yourself.a40 By October 1838, Texians had evidence that Mexican agents, Manuel Flores and Pedro Miracle, had visited Indians of northeast Texas to instigate war against frontier settlements.a41 Threats of a bloody massacre kept the scattered outposts in a state of alarm. With his strong show of force against Cordova, Rusk made himself an even more popular figure. There was talk of his running for president in the fall elections.a42

When demand pressed Ferris back to surveying in late 1838, he found it hard to employ work crews. Most of the able-bodied men of East Texas were participating in the pursuit of Cordova, which took an Anglo army onto the prairies of North Texas for the first time.

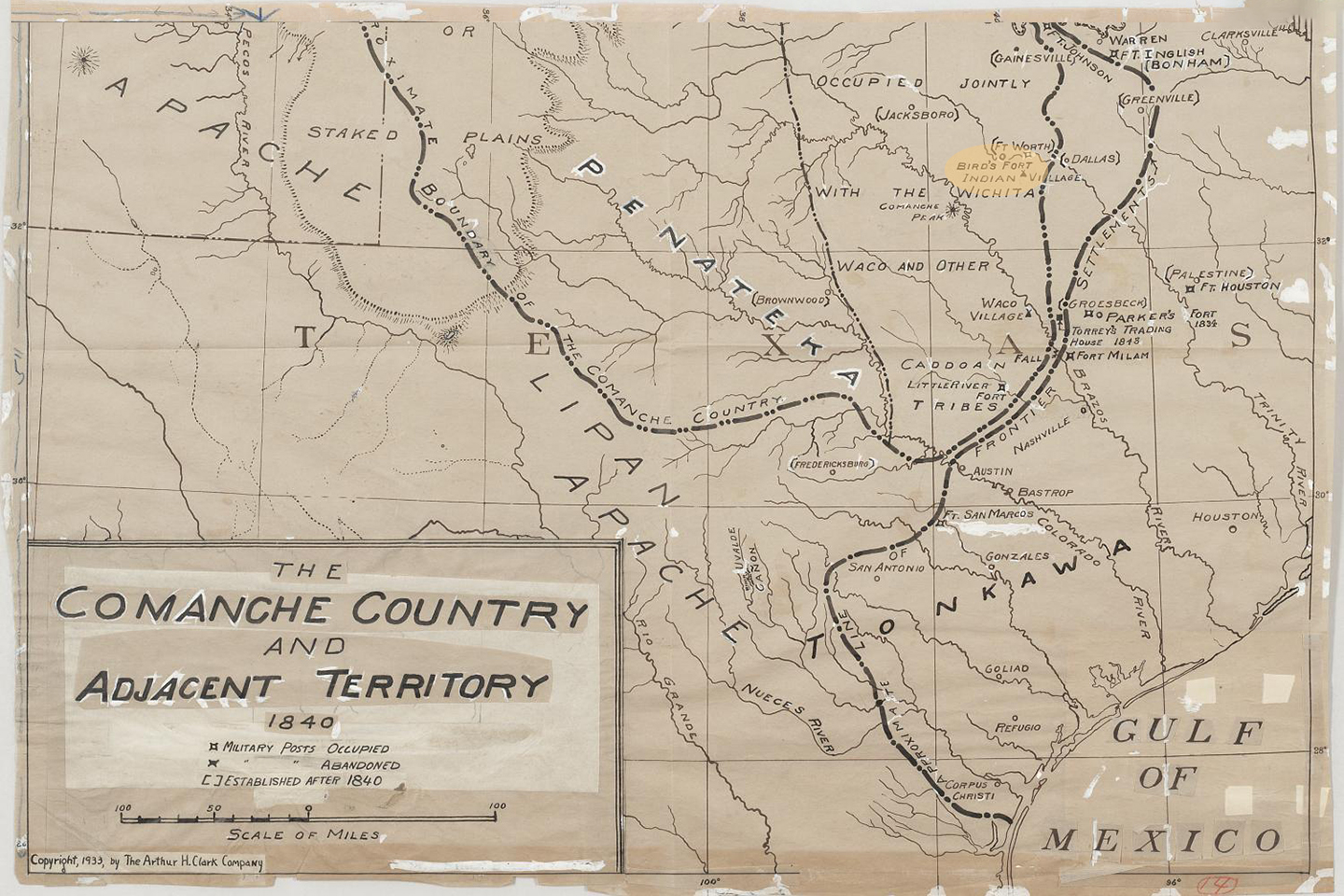

Three companies of militia from Red River and Fannin Counties, under Gen. John H. Dyer rendezvoused at Fort Inglish (now Bonham, Texas) and scouted the Three Forks area in September and October of 1838. Rusk's troops left Nacogdoches on November 16 and proceeded through the Cherokee Reserve where the general satisfied himself that those Indians were not involved in the Cordova Rebellion. In early December, Rusk located Dyer's Fourth Brigade on the Elm Fork of the Trinity about twenty miles above the Three Forks (now Denton County). Five hundred well-armed, mounted Texians thus made a show of force on the prairies which heretofore had been safe refuge for the tribes. They failed to find Cordova, who reportedly withdrew westward; neither did they find hostile Indians, although they burned several deserted Indian villages.a43

It was an unusually harsh winter with howling "northers." Warren Ferris, who was surveying on the Angelina and Sabine Rivers that winter, recalled "severe northers succeeding each other with little intermission; boys skated on the ponds near Nacogdoches.a44 On the Texas prairie west of the Trinity River, the Indians fell back, burning grassland as they retreated, destroying forage, and driving off the game.a45 Finally the Anglo army, short of supplies and with their horses exhausted, was forced to turn back to the East Texas settlements. Gen. Hugh McLeod called the bitter cold march across a barren prairie "unparalleled since DeSoto's." He reported the prairie land to be the "finest portion of Texas" and judged the Indians would "perceive the hopelessness of the contest," having seen that the white man could sustain such a campaign on the prairies in the winter.a46 As the militia returned to Clarksville, Nacogdoches, and San Augustine, many men were convinced that the enemy in their midst was the Cherokees and their leader, Chief Bowl.

How deeply the Cherokee were involved in the 1838 Mexican Rebellion became a matter of dispute. Chief Bowl, war chieftain of the Cherokees, protested innocence to his friend Sam Houston. Alarmed by white aggression, Bowl wrote Houston, "my people from the Bigest [sic] to the least have a little dread on their minds.a47 Houston believed the Cherokees had a right to their land. His strong condemnation of violations of Indian treaty rights alienated many of his East Texas backers who thought him more Cherokee than Anglo in his sympathies. Reassuring Chief Bowl, Houston wrote, "I have given an order ... no families or children of Indians shall be disturbed or have troubles ... they shall be protected and even the Mexican families, and property shall not be troubled." He urged the Cherokees to keep the peace as they had promised in the treaty; ironically, he recommended they put their trust in General Rusk as their protector. "Look to him as your great friend," Houston counseled.a48

Warning Rusk not to invade the Cherokee Reserve and instructing Alexander Horton to survey and clarify the Cherokee boundary line with all speed, Houston left Nacogdoches for Houston City. But Houston's conciliatory Indian policy was doomed. In the fall of 1838, a new president would be elected since, under the Texas Constitution, Sam Houston could not succeed himself. The power of the protector of Indian rights was on the wane; the influence of Anglo-Texan land speculators was on the rise.

In November 1838, Houston received a report from Alexander Horton that the boundary between the Cherokees and their white neighbors had been run, despite obstacles thrown up by Isaac W. Burton and others in the Nacogdoches area. Horton, who helped negotiate the 1836 Cherokee Treaty, informed Houston that despite every "art, villainy, corruption and treachery" the Anglos could invent, "We have succeeded . . . the Indians are all well satisfied, and will remain in peace if the Whites will let them alone."a49

Assigning blame for the critical Texas/Indian predicament is not a simple task. The United States chargé d'affairs to the Republic of Texas wrote to his superiors in the State Department that the situation was "mainly attributable to the conduct of some of her [Texas] citizens, who have unwisely irritated and provoked their savage enemy by trespassing upon and surveying their lands.a50 Houston, whose hands were tied, told his friend Andrew Jackson that the bloodshed on the Texas frontier was due to the "violence of the American character." In his final address to Congress, Houston condemned a "few seditious speculators" who would "involve the country in a general Indian war." Then he left Texas for an extended visit to the United States.a51

In point of fact, conflict was guaranteed from the moment the Texas Senate nullified the Cherokee Treaty in late 1837. That act signaled white settlers in East Texas that the reserved land was up for grabs. When the Land Office opened, settlers began to flood Cherokee lands. Early Texas historian Henderson Yoakum faulted whites for provocation, saying that the "ink was hardly dry till surveyors were in the reserve." Surveyors, eager to locate the best lands along streams, went deep into Cherokee country. Yoakum asserted: "The Indians, seeing them at work, were not slow to believe what the Mexicans had told them--that the white people would take all their hunting-grounds, and drive them off.a52

Although Houston led Chief Bowl to believe that the treaty was still viable, running of the Cherokee Boundary was a moot issue. Houston was as unable to control the settlers and speculators as Chief Bowl was unable to control the dissidents in his tribe. Houston observed: "The Indian lands are the forbidden fruit in the midst of the garden,a53 and Anglo settlers were not to be denied.

When Mirabeau B. Lamar became president of Texas in late 1838, he initiated an aggressive Indian policy; sanctioning Rusk and Dyer's pursuit of Cordova, authorizing Hugh McLeod to launch a March expedition back to the Three Forks area, permitting surveyors to intrude provocatively on Indian lands, and looking for a pretext to expel the tribes from Texas.a54

Warren Ferris shared the view of most Texians who supported Lamar's hardline Indian policy. To them, the existence of an independent Indian nation within the Republic of Texas was preposterous. Although the civilized Cherokees were peaceful, sedentary farmers, Anglo-Texans deemed them bad neighbors. By virtue of their leadership among the tribes, the Cherokees were held responsible for the bad acts of others. Houston's "soft" Indian policy and his high-handed treatment of Congress while president contributed to increased anti-Houston feeling in the period 1838-1840. Isaac Burton, who admitted Houston was a man of uncommon natural abilities, denounced him as "dissipated, eccentric and vain."a55 Most Nacogdoches men scoffed at any guaranty of Indian lands as an unconscionable barrier to the inevitable advance of white civilization.

A cycle of violence was set in motion. The actions of white settlers, greedy speculators, and ambitious frontier surveyors like Ferris alarmed the tribes, which raided isolated frontier settlements. Anglo-Texans retaliated with military expeditions and construction of western blockhouses such as Ft. Houston (modern Palestine, Texas) on the Trinity River. Such encroachments heightened Indian fears and led to more raids. It was an old pattern of violence and reprisal.

Typical was the Killough Massacre, which occurred in October 1838. Members of the Killough, Wood, and Williams families settled on land in present Cherokee County, seven miles northwest of modern Jacksonville, in the heart of the Cherokee Reserve. Knowing their precarious situation, the farmers ventured out to clear the fields with their weapons close at hand; but, one tragic autumn day, they were caught without their rifles. In a sudden Indian attack, eighteen whites were killed or captured. Three Killough women fled on foot, one carrying a baby. They hid in the woods for days before being found by a friendly Cherokee who took them to refuge at Martin Lacy's fort.a56

An excuse to expel the Cherokees was found on May 14, 1839, when rangers killed notorious agent/provocateur Manuel Flores on the San Gabriel River near modern Georgetown. On Flores's body were found letters implicating the Cherokees in the Cordova Rebellion.a57

Lamar commissioned Martin Lacy, whose home was only four miles from Chief Bowl's camp, to deliver an ultimatum to the Cherokees. The president of the Texas Republic accused the Indians of murder, theft, and intrigue and ordered them to leave Texas or face extermination.a58 Young John H. Reagan, who came to Nacogdoches in May 1839 and, like Ferris, was befriended by Burton and Lacy, was an eyewitness at the Indian council in June and reported the tense scene. Elderly Chief Bowl received Lacy with courtesy and led the Texian delegation to a spring near his home where he sat on a log and listened in silence as an interpreter read Lamar's decree.

Although he admitted some renegades might be guilty of depredations for which they should be punished, Bowl vehemently denied the allegations against his tribe. He told Lacy that there had been a meeting of chiefs and head men in council. His young men were for war so, excepting himself and Big Mush, were the other major leaders.a59 They believed they could whip the whites, but Chief Bowl knew his tribe would ultimately face defeat. Reagan was impressed with the dignity and candor of the eighty-three-year-old Bowl, who was resigned to his fate as leader of his people. "If he fought, the whites would kill him, and if he refused to fight, his own people would kill him. ... [He had led his people a long time. ... [HIe felt it his duty to stand by them.a60

Thus Bowl rejected Lamar's ultimatum and stated his determination to defend the lands guaranteed by the 1836 treaty. When Lamar countered by ordering the military to build a fort in Cherokee territory at Neches saline, Bowl concentrated his people east of the Neches River near that site.a61

On July 1, 1839, a so-called "Peace Commission" entered the Reserve to supervise Cherokee removal. Composed of military men and hard-liners on Indian policy, the commission included David G. Burnet, T. J. Rusk, and Isaac Burton. Chief Bowl agreed to withdraw to the Cherokee settlements in western Arkansas (Indian Territory) but requested a delay to harvest the fall corn crop. For two weeks, both sides stalled for time. While the negotiations went on, Gen. Edward Burleson and Gen. Kelsey H. Douglass were readying troops. Whatever the outcome of the talks, the Cherokees were to be evicted; they were the chief impediment to Anglo-Texan expansion onto the rich prairies of north central Texas.

Troops of the Texas militia and regular army under Rusk, Johnston, Burnet, McLeod, Burleson, and Douglass camped six miles east of Bowl's position. Following an argument over command, militia leader K. H. Douglass was chosen commander-in-chiefa62 Warren Ferris was with the Nacogdoches militia under General Douglass's command. In fact, almost every able-bodied man in East Texas was present, including Nacogdoches financier Adolphus Sterne.

On July 15, Chief Bowl broke off talks and moved his encampment to the west bank of the Neches (now Henderson County)a63 The Texians pursued, first exchanging fire with the Indians that afternoon when some twenty-five men under Rusk engaged Cherokee warriors located by a spy company. The Indians advanced, fired, and then fell back into a thicket and ravine. Lines were formed and, under a blazing July sun, the battle was joined. Withering gunfire, blistering heat, and heavy smoke took their toll. When the first day's battle ended at sundown, two Texans and eighteen Indians were dead.

At mid-morning on the second day of the Battle of the Neches, Texian troops moved out in two regiments, advancing up both banks of the river. Again, a spy company located the Indians, this time in a cornfield. Troops under Burleson and Rusk arrived on the scene, charged, and exchanged a brisk fire before the Indians retreated into the thickets of the river bottom. There the main body of the Texian army engaged about 500 Cherokees formed in a line that extended a mile.a64

Chief Bowl rode back and forth behind the Indian line. Conspicuously dressed Anglo-style in a black military hat, a silk vest, a sash, and the sword given him by Sam Houston, he recklessly exposed himself to gunfire from the Texians. When the Cherokees retreated, Bowl was among the last to leave the field. He was wounded when his horse was shot from under him. Another shot caught him in the back. Then, despite John Reagan's attempted intervention to save his life, Bowl took a pistol shot in the back of the head which killed him instantly.a65 The second day's fighting, near present-day Tyler, Texas, lasted no more than two hours. Their leader dead, the Cherokees withdrew toward the Red River. Texian troops pursued, driving Indian warriors, women, and children, sick and wounded across the river into Arkansas. On July 25, the Texas army disbanded and returned home.

Following the July campaign, Ferris was with General Rusk, Robert W. Smith, and a troop of some forty men on a scouting mission in the old Cherokee Reserve. Reports circulated that hostile Indians were still in the area, perhaps returned to gather corn, so it was decided to make a forced march to the Sabine River and return via another route before the Indians could concentrate an attack. Taking every precaution against surprise, they advanced briskly through Indian country. Camped one night after seeing "mockasin" tracks all day, the recruits heard an unearthly chorus of wolves and owls. Convinced the calls were Indian signals, they panicked and fled the camp pell-mell into the darkness. Ferris recalled how they silently forced their way through heavy brush, making no great progress. At length, they found themselves dragging through a blackberry bramble. "Our pants were torn off to the knees," Ferris remembered, "our coattails . . . were left on the brambles ... we might have been trailed by the commingled blood of ourselves and horses.a66

When they finally regained their courage and regrouped, the troop felt rather sheepish. Warren Ferris wrote:

We afterward ascertained that the owls and wolves that sent us out on the blackberry expedition were in reality Indians . .. that the celerity of our movements and midnight excursion saved us; that our retreat at the moment was a necessary and prudent course."a67

On their return to Nacogdoches, Ferris and his fellow volunteers did not boast much of their achievements on this brief campaign but later convinced themselves that only forethought had saved their lives and that the Indians, probably thinking them the vanguard of a larger force, had cleared the area.

The Cherokee barrier was removed, rich lands were open to white settlement, and the surveying business again flourished. Swamped with profitable work, Ferris wrote an exultant letter to Sarah Lovejoy, proclaiming "Land is the cry!" He echoed the tenor of the times when he wrote:

There are many who sacrifice honor and all things else to the God property. ... Speak to one his answer is Land. Enquire kindly of his family and he answers in Leagues and Labors. The Land Mania is great . .. when in Turkey do as the Turkeys do, and say Land also,—until I possess enough for future good, and for the future wealth of myself and relations. ... We have had some trifling difficulties with the Indians. We have whipped off the Cherokees. I advocated the measure when it was not popular. It is good but they annoy us some still—at times.a68

Ferris's endorsement of the Cherokee expulsion was not shared by Sam Houston. On his return to Texas, Houston learned the fate of his adopted tribe and was outraged. At a public meeting in Nacogdoches, he denounced the actions of greedy speculators and aggressive militarists who had violated the good faith of the Cherokee Treaty. He proclaimed Chief Bowl a better man than his "murderers." Some of his Nacogdoches friends, like Rusk, Sterne, and Raguet, would not forgive Sam Houston of these accusations for years. They were even more dismayed when, as a San Augustine delegate to the Texas legislature, Houston introduced a bill barring land speculation in the Cherokee Reserve. In a speech on December 3, 1839, Houston decried the injustice of the campaign against the Cherokees, denouncing the fraud and greed which motivated their expulsion. He proposed that Cherokee land be treated as public domain, sectioned in 640-acre tracts, and offered at public sale. Houston reasoned such action would bring eighteen million dollars into the empty treasury of the Republic, instead of enriching the pockets of speculators.

Enraged when Burleson and McLeod presented him Bowl's bullet-pierced black hat as a souvenir of the Cherokee War, Houston lost all moderation and accused the Lamar/Burnet government of being the tool of land speculators. "The war," he said, "was produced by the encroachment of the speculators—[their] locations were not made in good faith—and if we now confirm them in their illegal locations, the bloodshed in the Cherokee war will rest on our own shoulders." The Texas Congress, unable to oppose a measure so obviously benefiting the majority, passed the Cherokee Land Bill unanimously in January 1840, but Sam Houston had made powerful enemies.a69

Through two years of Indian campaigns and erratic surveying expeditions, Nacogdoches County Surveyor Ferris exchanged letters with Land Commissioner Borden, explaining that illness and military duties had delayed his preparation of the map of the county. Ferris had divided the county into subdistricts, assigning one district to each of his deputies. He relied on them to bring in accurate maps which, pieced together, would satisfy Borden's request for a "true" picture of boundaries and claims. Ferris complained of the impossible situation in trying to use old surveys:

I shall forward in a day or two one [map] to be found with the dates I possess, conjecture, conflicting accounts of others. Had you required me to mark the surveys previously made you would have been presented with a piece of network that would baffle description, were it possible to accomplish it.a70

Borden, in disappointment, replied:

It is much to be regretted that you are not in possession of the necessary information for representing the old surveys . .. the relative positions of the different parts, the true distances from one to the other appeared to be from actual survey: consequently, it will be impossible to know from the map where the work between two rivers will meet or in what manner they will join.a71

In late 1839, Ferris finally forwarded a map to the Land Office at the new capital in Austin.a72 Its only points of determination were streams, rivers, and Indian trails crisscrossing the vast area. The ban against survey of Cherokee lands made it impossible to anchor the new surveys to older ones in Nacogdoches County.

When the Land Office called Ferris's map useless, he responded with eight reasons his deputies failed to provide accurate or complete maps of their respective districts. Obstacles he listed included: former surveyors left no copies of field notes or plats; earlier government agents had issued titles prescribing points no longer to be found; previous surveyors had been careless in establishing definite locations; names of streams (the most certain existing guides to surveyors) had been changed; and described boundaries often contained more land than called for in the title. According to Ferris, public opinion pronounced the old surveys invalid, even though they had not been officially declared void. Finally, Ferris asserted that his deputies were unwilling to run survey lines for $3 a mile (Texas money) while hostile Indians still roamed the frontier.a73

Roving bands of Indian raiders were especially vengeful toward surveying parties. Although they traveled heavily armed, often with guards, surveyors could not work and carry rifles. Like every frontiersman, Warren Ferris had heard tales of Indians wrecking surveyors' camps, smashing their compasses, and scalping the surveyors. His own paper, the Nacogdoches Chronicle, carried the story of the death of surveyor Richard Sparks, surprised on the prairie, shot while attempting to survey land on the upper Trinity River.a74 In another notorious incident, the "Battle Creek Fight," which occurred on Richland Creek in present Navarro County within three days of the Killough Massacre in October 1838, a surveying party of twenty-five was attacked by 300 Kickapoos. Under cover of darkness the surveyors tried to reach a timbered thicket; only six survived. In 1839, W. P. Brashear, foolishly surveying alone and unarmed in LaVaca County near the Texas coast, was surprised by Comanches and barely escaped with his life on his horse "Git Out." Frontier surveyor John Harvey warned, "When you least expect Indians, there they are."a75 In the mid-1840s, Frederick Roemer commented: "the Texas surveyor finds his rifle just as necessary as his compass. ... [H]ostile Indians ... know full well that the surveyor is only the forerunner of the white intruder. ... Therefore they pursue him with particular hatred."a76

Such were the hazards of a frontier surveyor. Under constant pressure from clients and superiors in the Land Office, Ferris wrote to Buffalo of his mounting feelings of isolation and loneliness. He admitted that he longed to hear from his family and few loyal friends and that he was "sometimes in a sentimental mood." To sister Sarah he wrote:

I am here among a set of worst possible ill dispositioned people who possess no feelings in common with me and I am in consequence lonesome. ... some disagreeable reflections ... cross my mind when I am idle. ... when reverses occur. I wish much you were here to enjoy the finest climate in the world and be near or with me.a77

Warren Ferris wrote that money was scarce, but said "Texas is disposed to enjoy herself" even without money. Although social occasions abounded and Nacogdoches boasted "fair specimens of beauty," Ferris claimed that he shunned polite society. He found no one to be trusted. Even Senator Burton might not be useful to him or Charles much longer; Ferris predicted that Burton's reputation would not "long buffet the storm" of "vindictive malice, envy and scandal" which flourished in the young Republic.a78

The pinch of depression in the United States was being felt even in distant Texas. Faced with a worsening economic situation and an increased sense of urgency to make himself financially secure, Ferris decided to take some risk. In a letter to Joshua Lovejoy, Ferris described the forces which drove him to take extreme measures. The issuance of cheap paper by the government caused depreciation of Texas money to but a quarter of its face value.a79 Since county surveyors were required to accept payment in the devalued currency, Ferris felt compelled to seek other income. "I immediately turned my attention," he wrote, "to a Surveying Expedition to the Three Forks of Trinity, a Section occupied by our most incorrigible foes."a80

In August 1839, the official surveyor of Nacogdoches County was approached by Dr. William P. King, a Mississippi land speculator. Dr. King's Southern Land Company, headquartered in San Augustine,a81 hired Ferris to survey a new town at the Three Forks of the Trinity. The town "Warwick" was to be the centerpiece of a huge land promotion from which Ferris would profit enormously. Caught up in the dazzle of land speculation, Warren Angus Ferris made four desperate attempts to enter the wilderness at the headwaters of the Trinity River during the autumn of 1839.

At the Three Forks

Reports of a veritable garden spot on the upper Trinity Riverb1 in North Texas aroused the interest of speculators in distant Mississippi who, in 1838, organized the Southern Land Company and, in 1839, enlisted Nacogdoches County Surveyor Warren A. Ferris to locate land in the newly opened territory. Dr. William P. King,b2 president of the land company whose organizers first met in Vicksburg and then Holly Springs, Mississippi, came to Texas, made his headquarters at San Augustine, began to buy up land certificates, and approached Ferris as a knowledgeable and ambitious associate.

Although it was illegal under the laws of the Republic for county surveyors to locate land for private companies, Warren Ferris signed a contract with King on August 28, 1839. Ferris was to locate ninety leagues and labors (around 400,000 acres) on the Trinity River beyond the former Cherokee Reserve. On return of his field notes, Ferris would receive $900, out of which he was to pay expenses of the expedition. On the strength of his agreement with Ferris, Dr. King sold over 200 shares in the Southern Land Company on a single day, August 30. A second contract, signed September 4, 1839, stipulated that Ferris was to survey land on a bluff of the Trinity at the Three Forks. This site, to be designated the "city of Warwick," would have been the precise location that later became the city of Dallas. Ferris himself was to receive one-twelfth interest in Warwick City.b3 It was this prospect of rich reward in speculative lands that led Warren Ferris to risk his reputation and to make four desperate attempts to locate the Three Forks of the Trinity in the fall of 1839.

The area which would be Dallas County was known to early Texians as the "Three Forks," a reference to the confluence of the Elm, West, and East (Bois d'arc) Forks of Rio Trinidad.b4 It was a region of startling contrast to the Piney Woods of East Texas. Forested, sandy land gave way abruptly to a virtually treeless prairie with rolling hills carpeted in tall native grasses and broken by streams along which elm, oak, hickory, and mesquite trees grew, sometimes forming dense thickets in the bottom lands. The deep, black, waxy prairie soil, although viewed with initial suspicion by Southerners accustomed to sandy land, was the fertile stuff of a farmer's dream. From the north and west, reaching like long, skinny fingers into the Blackland Prairie, ran lines of thin sandy soil topped by blackjack and post oaks—the Eastern Cross Timbers.b5

Although Spanish and Mexican authorities claimed the Three Forks region on vague maps, neither really controlled it. North central Texas still belonged to the Indians. It was the meeting ground of numerous tribes who camped and traded along Turtle Creek, at Cedar Springs, and along White Rock Creek. Two major Indian footpaths (or traces) crossed the Three Forks from east to west. One, the Kickapoo Trace, entered present Dallas County from the southeast, near modern Seagoville, and proceeded to a ford across the Trinity, at approximately the junction of Commerce Street and Industrial Boulevard in the present city of Dallas. From there, the Trace continued west, skirting the outcropping of Chalk Hill in modern Oak Cliff, crossing Mountain Creek to the Indian campsites on Village Creek in present Tarrant County. Another Indian trail, the Caddo Trace, crossed the northeast corner of what is now Dallas County, near present Sachse and Garland.b6 Following these Indian routes, bands of Wichitas (called variously Keechies, Ionies, Tawakoni, and Towash), as well as Kickapoos, Caddoes, and Cherokees moved through the Three Forks to camp along the tree-shaded streams. The Indian traces were also a favored route for Comanche war parties that swept in off the western plains to raid isolated settlements and confront intruding surveyors bearing that hated instrument, the compass, "the thing that steals the land."b7

Warren Ferris's attempts to locate King's speculative city of Warwick on a bluff at the Three Forks of the Trinity were frustrated by Indian harassment and an unexpected difficulty in pinpointing the actual confluence of three streams. Extremes in weather, either drought or flood, confused the issue. Indeed, the existence of a point at which three streams met proved to be an illusion. Only the Elm and West Forks converged near a bluff; the mouth of the East Fork was thirty miles downstream.b8

Enthusiastic about his new assignment, Ferris invested his own meager savings in four expeditions to the Trinity in the fall of 1839.b9 In early September, with fifty-five men from Nacogdoches and again in late September with forty-four men, he tried to penetrate the Indian-controlled territory, but the sight of fresh moccasin tracks caused both expeditions to turn back. In early October, a third, better-organized attempt was made. Ferris divided his sixty men into three divisions, spent some time in the former Cherokee Reserve preparing provisions, and then made his first survey along White Rock Creek in what would be Dallas County. Again the presence of hostile Indians forced the surveyors back to the East Texas settlements.

His repeated efforts gave Ferris the reputation of an enterprising fellow, but most folks in Nacogdoches judged the survey of the Three Forks to be impractical under the circumstances. Few were willing to hazard Indian Country so soon after the Cherokee War. Finally, in November, Ferris succeeded in recruiting twenty-nine men. Well-armed and provisioned, the fourth expedition traveled slowly westward for about twelve days before they discovered signs of Indians. This time, the surveyors pursued the Indians and found them lying in ambush in a canebrake. "We charged," Ferris wrote with some pride, "and your humble servant Shot one through the heart at the distance of Eighty yards." When the rest of the Indians fled, Ferris and his men located their camp, finding five horses and provisions including meat, corn, beans, axes, ropes, and kettles. The slain Indian was armed with an amazing mix of weaponry—"an English Rifle, a Prussian Pistol, A Bowie Knife—A Butcher Knife and Bow and arrows."b10 Two days later, after seeing indications of a larger Indian party entering the area, all but four of Ferris's men refused to stay longer in the Three Forks region and deserted him.

One of the four intrepid souls who stayed with Ferris was John H. Reagan. In his memoirs, Reagan recalled how the party traveled light, each taking only a blanket, corn flour, meat, coffee, tin cups, compass, chain, field book, and hatchet. Moving swiftly and silently by night, they reached Cedar Creek on the East Fork of the Trinity; often they were forced to hide by day in damp, cold creek beds and Reagan fell ill with chills and fever.b11 Finally, Ferris admitted that the Indians were too numerous to attempt surveys. Having satisfied himself by exploring the country, he led his men back to Nacogdoches.

Warren Ferris proclaimed his intention to resume surveying in 1840 as soon as he could raise another expedition. Not having corresponded with his Buffalo family in nearly a year, he shared the news of his fantastic financial opportunity with his half-brother Joshua Lovejoy, cautioning:

No part of the information contained in this letter is known to our folks ... it is absolutely necessary to keep my arrangement with the Southern Land Company a profound secret. I must only be known as County Surveyor of Nacogdoches County.b12

As soon as the weather began to improve in the spring of 1840, Ferris was back in the field. With John Reagan as his deputy, he spent a month surveying in what is now southern Van Zandt County. Rain dogged the surveyors. They returned to Nacogdoches in May, barely having made expenses.b13

Since Ferris had exhausted his personal finances in 1839, his 1840 surveying for the Southern Land Company was backed by the company itself. Dr. King refinanced the value of stock from $500,000 to $650,000, selling more shares and generating credit in East Texas to outfit the expeditions.b14 Stockholders cosigned a note to K. H. Douglass and Nicholas H. Darnell, merchants of Nacogdoches and San Augustine; both men agreed to be paid in land.b15 Similar agreements were reached with several individuals who signed on as assistants or guards. In addition to his post as official county surveyor and his rank as captain in the militia, Warren Ferris now carried the title "Topographical Engineer of the Southern Land Company of Texas" and owned fifty shares in the company, valued at $200 each. He was promised a fee of $5,000, "good money, U.S.," plus expenses to lead the 1840 expedition and complete the surveying in forty days.b16

On the eve of this fifth attempt to locate the Three Forks, Ferris wrote a long, gossipy letter to his brother in Buffalo. He reported himself well and said that he had penetrated "twice to Three forks of Trinity . . . once with 4 men and once with 5—hell of a crowd—didn't do anything first trip—Indians too deep. Second trip barely paid expenses." Concerning his bargain with King, Warren Ferris urged his brother to keep "Mum—must be secret I am County Surveyor yet and in public only County Surveyor."b17

For the first time, Ferris's optimism seemed to waver. Even the most sanguine booster knew the Texas Republic was in deep economic depression. Speculative enterprises like that of Dr. King were in trouble, gambling as they did on continued prosperity, increasing immigration, and rising land prices. Warren Ferris recognized that time was running out for the land boom in Texas. Of the economy, he wrote: "Nacogdoches on the wane. Texas bankrupt and her people rogues. ... Times as hard as Millstones. Promissory notes not worth a damn. ... Gold and silver fled forever and U.S. Banks all broke."b18

Concerning Texas politics, Ferris informed Charles that Lamar's popularity declined as Sam Houston's soared upward. "He'll be next President, got no body popular enough to oppose him," Ferris judged. Everything was quiet on the Indian frontier, although the Mexicans still threatened invasion. During the peaceful interlude, Burton and other planters grew cotton and corn on what had been Cherokee land. Sensing that speculative opportunity was running out, Ferris urged Charles to take "the shute to Texas" as soon as possible, for "Texas owes us something somehow or other."b19

One day after posting this letter, on June 3, 1840, Warren Ferris left Nacogdoches with a party of twenty-nine men. The surveyors, their guards, and assistants followed the old Cherokee Road to Neches saline, then the Kickapoo Trace through present Van Zandt, Kaufman, and Dallas Counties (roughly following present U.S. Hwy. 175) to the Three Forks region. This time Ferris was accompanied by Dr. William P. King himself, determined to survey his empire on the Trinity.

Again they divided into three surveying parties; one group under Robert A. Terrellb20 was detailed to follow the Kickapoo Trace to its crossing of the Trinity, there to locate the Three Forks and lay out the city of Warwick. An extremely dry July caused the river to run so low that Terrell was unable to determine a point where three streams met. The location of Warwick City was postponed. Ferris later described the 1840 drought conditions: "all the streams were low; the East Fork of the Trinity dry; and the clouds of dust could be seen in every direction raised by buffalo and wild horses, and water was to be found only in holes."b21

King and Ferris established the northwest corner of the proposed King Block of surveys at White Rock Creek in present Dallas County, approximately where the creek now crosses Samuell Boulevard (or Ferguson Road). Following the direction of the streams, all lines ran northwest and southeast from that point, establishing the line for subsequent surveys. As completed, the King Block was 22 miles wide and 29-1/2 miles long. If outlined on a modern map, the northwest corner would be a mile and a half due east of White Rock Dam, the northeast corner about a mile north of Lake Lavon in Collin County, the southwest corner midway between Kemp and Kaufman in Kaufman County, and the southeast corner about a mile east of Van in Van Zandt County.b22

During June and July of 1840, teams of surveyors under deputies R. A. Terrell, George W. Casey, John H. Reagan, and E. B. Harvey completed 118 marked surveys, each for a league and a labor. The King Block totaled 543,390 acres, overlapping six counties of present-day Texas.b23 Unfortunately for King and his associates, many of the certificates issued by land boards in Shelby, Sabine, and San Augustine Counties were judged to be fraudulent, and the surveys based on them were subsequently rejected by the General Land Office in Austin.b24 Only four of the twenty-nine surveys made by Ferris in present Dallas County retain their original lines. These are all on the east side of the county and do not bear the names of the original owners. They are the T. Thomas, John Little, Daniel Tanner, and John P. Anderson Surveys.b25

Ferris's problems coordinating the work of several deputies were revealed in his instructions to John Reagan. He ordered Reagan to cease all surveying north of the East Fork of the Trinity as E. B. Harvey had already selected and surveyed sections in that area. Reagan was to forward a plat of his work so that overlapping surveys might be avoided. "These instructions you will strictly obey," Ferris wrote, "as no end would be found to the difficulties that a contrary course would produce."b26

Ferris returned to Nacogdoches in early August 1840, flush with the success of the summer expedition. From May to August 1840, he had completed a huge task of surveying, despite fevers that struck his men, killing one and forcing most of the others to return to the settlements. "My Expenses," he reported to Joshua Lovejoy in Kentucky, "were about one thousand dollars and for ninety of the ... Leagues I am to receive five thousand dollars. ... The ballance [sic] of said surveys are worth to me one hundred dollars Each—."b27

In the first surviving description of the Dallas area in late spring and early summer, Ferris waxed eloquent on the beauty of the North Texas prairies:

I saw in the picturesque regions there much of the wild soul-stirring scenes with which I had been so familliar [sic] in the Mountains. Thousands of buffalo and Wild horses were everywhere to be met with. Deer and Turkeys always in view and an occasional Bear would sometimes cross our path-Wolves and Buzzards became our familliar [sic] acquaintances and in the river we found abundance of fish from minnows to 8 footers. The Prairies are boundless and present a most beautiful appearance being extremely fertile and crowned with flowers of every hue.b28

Since Charles Ferris was still in Buffalo trying to sort out the family finances, Warren decided to invite Joshua to come to Texas; they could work a partnership, and Ferris could put his land claims in Joshua Lovejoy's name. Ferris pressed Josh to "come to Texas ... and get a few thousand acres of Land which would be a fortune for you some ten years hence and it is now easily had."b29 Promising a welcome and a job surveying to his younger half-brother, Ferris made it clear that he was "going out for sake of profit." His personal philosophy was revealed when he told Joshua:

Money is the modern God worshipped by all the World. ... Man is now respected, not in proportion to his learning, or his honesty no he is weighed in the ballance [sic] of dollars and cents and valued accordingly. Acquire wealth and you can accomplish anything.b30

By inviting young Lovejoy to Texas as his partner, Ferris hoped to avoid any possible criticism of his land dealings with Dr. King; but, who was Joshua Lovejoy and what kind of partner would he make? Ferris's decision to ally himself with Josh proved to be ill-advised.

Joshua Lovejoy drew mixed reports from his family in Buffalo. He apparently left Michigan on the run from debts and sexual indiscretions. In May 1839, Charles Ferris instructed Josh to come home and work in the Buffalo post office: "Bring all your things with you and let Michigan go to hell if it pleases. ... Don't delay then any longer but come home and leave that damned state forever-come directly."b31

Following his older brother's advice and his own instincts for survival, Lovejoy returned to Buffalo in the fall of 1839. He worked briefly for the Buffalonian; but, restless for adventure, the young romantic soon headed south. He got as far as Louisville, Kentucky, before he ran out of money. In his first letter to Ferris from Kentucky, he described how he resorted to teaching in a small country school near Shelbyville. Lovejoy surprised himself, teaching subjects he had not studied since he was fourteen. He successfully bluffed his way until near the end of the term when, after expelling two boys and refusing to back down to their irate parents, he lost his job. Luckily, he got another school at nearby Calloway Corners in Henry County. Lovejoy described Kentucky as "not refined" but judged it "better to be a king among hogs than a Hog among Kings." Asking Ferris of prospects in Texas, Lovejoy pronounced himself reformed of all bad habits. He was "Now a Whig and a Christian who was once a Democrat and a Dandy."b32

Sisters Louisa and Sarah Lovejoy portrayed their brother in a favorable light. Louisa wrote to Ferris, "Brother Joshua is very handsome, very talented and one of the best fellows ever created." Sarah, who knew more of Joshua than she admitted, described the half-brother Ferris had not seen in twelve years:

Who is he? Shall I describe him to you? Years have passed since you have seen him, the years that either model or entirely change the character of the boy. Well! With a personal appearance most remarkably prepossessing, he joins a perfection of manner rarely met and with a temperament essentially poetick [sic], he mingles strong independent good sense, a generous heart, and a knowledge of the world singular in one so young. Are not these the elements of a great character.b33

The family in Buffalo, Ferris in Texas, and Lovejoy in Kentucky expected Charles Ferris to depart from Buffalo any day during 1840. Joshua anticipated Charles traveling to Texas via Kentucky to bring him books and pistols, but Charles did not appear. Economic hard times, family duties, and poor health delayed his departure.b34

Charles Ferris's situation in Buffalo was clarified in an April 1840 family letter to Texas. Charles sold his interest in the Buffalonian to his partner, realizing $450 which he hoped to use to travel south,b35 but he found it difficult to collect the money due him. The four-year dispute with Henry Lovejoy was settled, leaving the Ferris Lovejoy family with three acres of prime city property which they could not sell and on which they could barely pay taxes.b36

Charles reported that their mother, age fifty-two, looked not a bit older, Sister Sarah was "very smart," and Louisa "very pretty and . . . witty." Louisa's added note quizzed Warren, "Tell me if some bright-eyed Southern girl has not stolen your heart, or if it is as you always affirmed, invulnerable."b37 For her part, Sarah wrote that she had seen Ferris's old acquaintance from the mountains, Sir William Drummond Stewart, and she pondered:

Strange that men accustomed to all the luxuries and refinements of civillised [sic] life should find such charm in the boundless prairies and forests of the west, in spite of the many dangers and privations they must necessarily encounter. Yet there are many such—my brother among the number.b38

During the fall of 1840, Sarah Lovejoy informed Joshua: "Charles is quite a literary person now. ... He has written a prize song this summer—won the Hard Cider, Log Cabin Cup, made a speech when it was presented and had three rounds of applause.b39 It was little more than a piece of doggerel that Charles Ferris penned and Tom Nichols set to music, but the family took pleasure in the recognition won for producing the best political song to be used in William Henry Harrison's local presidential campaign. Ironically, Charles Ferris was an ardent Democrat. In his acceptance of the cup, which proved to be pewter, Ferris gave rare praise to his city:

Buffalo, though not my birthplace, was my cradle. Hardly were the embers of its destruction cold when it became my home. ... I watched its growth, from the weakness of infancy to its present pride and strength and beauty. ... The Queen City of the Lakes, justly celebrated for the beauty of its position, the salubrity of its climate, the extent of its resources, the enterprise of its inhabitants, the integrity and intelligence of its citizens, and the loveliness of its ladies.b40

Pursuit of his journalistic career led Ferris to assume editorship of The Phalanx, published by C. C. Bristol, the sarsaparilla manufacturer. A small paper advocating the philosophy of Charles Fourier and Albert Brisbane, it was the first daily in the United States devoted exclusively to social reform. Sarah Lovejoy wrote, "They are going to reform the world. I hope they succeed—but I have my doubts."b41 Editor and publisher were disappointed at the dearth of public interest; The Phalanx folded in six weeks.b42

Sarah Lovejoy reported that Charles Ferris had also written two plays; one a farce, the other a tragedy in five acts entitled "The Ottawa Chief at the Siege of Detroit." Sarah said Charles's latter work was performed once, "murdered," she claimed, when the leading actor got drunk and forgot his lines.b43 Literary efforts brought in little cash so, although his reputation as a writer grew, Ferris was back at the post office. Sarah explained, "It is impossible for him to get enough money to go to Texas. This care is constantly wearing on his health—he has been sick all winter. Poverty is dreadful to all but rich theorists."b44

While his brother struggled in Buffalo, Warren Ferris continued to urge Joshua Lovejoy to come to Texas. Josh was interested, but not convinced. To his sister he confided: "Warren's doing splendid—Go thou and do likewise so you will say. ... I don't like to throw away my talents. If I fall let it be with Eyes upon me—Not in the lone forest." To "defend a city filled with Ladies sooth them and make love—order troops—make a successful charge—return in triumph—ride thro' streets amid the thunder cheers," was more Lovejoy's style.b45 In July 1840, Lovejoy told Ferris to expect him in Texas after school ended in October: "I will try a life of adventure," Josh declared, "among the sublime western scenes a year or two, in order to gain health, energy and buoyancy. ... I feel that Hunting and/or Surveying on the broad prairies of the West will do me good." But Warren Ferris should have been forewarned when Joshua added:

I don't like Hard fare—I don't like fatigue—I don't like to risk my life unless there is an object of importance in the scene before me. I like the refinements of the City Life ... —Love—Ladies. ... I don't like to be buried in the Country.b46

Schoolteaching or, as Ferris put it, "Teaching the young ideas to shoot" was scarcely to Lovejoy's liking. Although he had many warm friends in Kentucky, Josh was more interested in fame and fortune and judged teaching "damned thankless employment.b47 When he wrote of his ambition to join the Texas Army, Ferris cautioned:

You speak of the Army. There was a time when I too thought that I would glory in nothing more than to land a victory but since as the Indians say I have got my belly full of military fame and Glory. I have seen hundreds bravely meet their enemies and perish and in a few short days their names were forgotten.b48

Joshua Lovejoy came to Texas bearing an assumed name. He had tried on a number of aliases, presumably to elude Michigan problems that might follow him south. He wrote to Sarah Lovejoy from Michigan in 1839:

I shall dress meanly change my name until I get money to enter Texas like a Gent. Julian FitzAlan LeRoy will answer until I get to Texas and then Clarence Linden Lovejoy or Clarence Auvergne L. will answer me thro' life. I must plot deep and consistent to sustain my name. I must not stay here long enough to be sued on my little affairs.b49

On leaving Buffalo, Josh signed himself "John Francis" Lovejoy. In May and June 1840 from Kentucky, he was calling himself "Julian Fitzallen" Lovejoy and relating his "damned scrapes" with Kentucky girls.b50 After much experimentation, he hit on a suitable alias. When Joshua came to Texas to become the partner of his half-brother, he came under a new (and, he hoped, luckier) "Texas name," that of Clarence Avon Lovejoy.b51

Warren Ferris's position as Nacogdoches County surveyor was up for election in September 1840. To clarify his status and open options for personal speculation in lands, Ferris did not seek reelection. The new county surveyor, A. A. Nelson, appointed Ferris his deputy, assigned to survey in the Three Forks country east of the Trinity River, including all of present Dallas and Rockwall and parts of Hunt, Kaufman, and Van Zandt Counties. At Fort Lacy west of Nacogdoches, Ferris began preparations for a fall expedition to the Three Forks. In a candid letter to Charles Ferris, he listed his assets and liabilities: "Should anything happen to me ... If I do not return ... Nelson has a little book containing my accounts whilst in office." These included land scrip for fourteen sections of 640 acres each, transferred to Ferris by King and Nelson, and his one-twelfth interest in the Warwick development. Signing "Yours till death," Ferris pledged his brother, "I shall if successful this trip quit venturing and lead some less dangerous and more quiet life.b52 With John H. Reagan, several chainbearers,b53 hunters, and guards, Ferris set out the second week in October on the Cherokee Road to Neches saline, then west on the Kickapoo Trace to King's Fort.

One of the chief problems for early travelers to North Central Texas was the lack of accessibility. An absence of any roads or reliable river transport seriously delayed settlement. Immigrants traveled through Louisiana via the Opelousas Road, up the Red River to Natchitoches, across the Sabine at Gaines Ferry; or they moved southwest from Fort Smith, Arkansas, along the Texas Road via Pecan Point and Jonesboro on the Red River. Either route then required an arduous overland journey along Indian traces from Nacogdoches or Clarksville. During the 1830s, Capt. Henry M. Shreve removed a "raft" of debris that blocked navigation of the upper Red River, making it navigable during high water between December and July.b54 Holland Coffee's trading post on the Red River near present-day Denison, Texas, then became the main gateway to north central Texas. Two other frontier outposts were Forts Warren and Inglish in present Fannin County, established by Abel Warren and Bailey Inglish in 1836 and 1837. An alternative to migration via the Red River was coastal steamer from New Orleans to Galveston, followed by a slow overland trip to Fort Houston on the Trinity.

In an effort to encourage immigration to North Texas, the Congress of the Republic in 1840 passed a Military Road Act, designed to open a road from the new capital Austin, north through Waco on the Brazos River, by the Three Forks of the Trinity, to Coffee's trading post on the Red River.b55 West of the road a series of forts was to be located to protect incoming settlers from Indians. To this end, Robert Sloan and an advanced party of road surveyors, followed by Col. William G. Cooke's main party, were in the Three Forks region in the fall of 1840.

Ferris's fall surveying expedition operated out of Fort King or Kingsboro, Dr. William P. King's stockade on a tributary of the East Fork of the Trinityb56 near present-day Kaufman, Texas. The fort, fifty miles upstream from Fort Houston, was the jumping-off point for surveying activities during 1840-1842. It consisted of four cabins surrounded by a wooden stockade enclosing three-quarters of an acre. From the frail fortress, a garrison of a dozen men defied the prairie Indians. It was the oldest permanent white settlement in the Three Forks region and was never abandoned during this period of frontier advancement.b57

From King's Fort, Warren Ferris's surveying party advanced to White Rock Creek to resume where they had quit surveying the King Block in July. Over the next eighteen months, most of present Dallas County, east of the Trinity River, was surveyed. In accordance with his instructions, Ferris located league and labor "donations" for veterans of the Texas Revolution. Few of these men actually came to live on this land; some was taken up by their descendants, but much was sold, exchanging land scrip for cash from speculators or newly arrived immigrants. The first numbered survey in what would be Dallas County was a large block east of modern Ferguson Road, in the name of Adolphus Rieman.b58

As he extended the northwest-southeast lines of the King Block, Ferris determined the direction of Dallas streets which, except in the central business district, follow the lines of his surveys. During late October, Ferris's men worked northwest up both sides of White Rock Creek to a point about a quarter of a mile south of the present intersection of Coit and Midway/Alpha Roads in North Dallas. Ferris paid his board back in Nacogdoches by surveying several plots for the Hyde family. He laid out a half-section for his employer A. A. Nelson; and, for himself, he surveyed three sections of land in the name of his half-brother, "C. A." Lovejoy. These were Lovejoy Surveys #8 and #9, now covered by White Rock Lake, and Survey #4, the present Forest Hills Addition.