The John Beemans: First Family of Dallas

Susanne Starling and M. C. Toyer

Legacies: A History Journal for Dallas and North Central Texas, Volume 32, Number 2, Fall 2020

This article includes popup citations. To read a citation, simply click on a citation number.

The Beemans are the founding family of Dallas. An early journalist described Dallas in 1842: "Col. Bryan in his tent and Capt. Gilbert in his cabin, constitutes the City of Dallas ... and the 3 Beeman families the county?"1 In that first year, John Neely Bryan was still a bachelor. The Mabel Gilbert family beat the Beemans by ten days in coming to Bryan's bluff, but they left after only two years. John Beeman, his half-brother, James J., and his nephew John S. and their families came to Dallas in April 1842, staked their claim on the "waters of White Rock Creek" and settled in to stay, thus becoming the first permanent resident family of Dallas County.

In the late 1830s, several families from Greene and Calhoun Counties in West Central Illinois became highly interested in Texas. Members of the Rattan family (Beeman cousins) migrated to Texas in the mid-1830s and sent back glowing reports which probably influenced John Beeman to purchase Toby scrip for 640 acres of Texas land.2 The availability of free or cheap land for his growing family motivated Beeman to sell the bulk of his holdings in Illinois to his brother William and make plans to move his family to Texas. This was a major life decision. It would be an arduous journey. He would be uprooting his pregnant wife and their eight children. John was the patriarch of the Beeman family: his decision convinced his young half-brother, James Jackson Beeman, and his nephew, John S. Beeman, and their families to also emigrate. Several Beeman neighbors, some of them relatives, joined the mass exodus to Texas, including members of the Hunnicutt, Moore, Cox, Rattan, Webb, and Silkwood families.3

John Beeman was a mature man of 43 years when he came to Texas. As a youngster, he was a private in the Illinois militia during the War of 1812. After that conflict, Beeman began to purchase land near the Wood River, married Emily Hunnicutt in 1823, and helped organize the Apple Creek Primitive Baptist Church. He became a prosperous farmer and stockman, operated a wood lot and a ferry on the Illinois River, served as justice of the peace, and ran for the Illinois legislature in 1836. It was no light decision to turn his back on these achievements and risk all in coming to Texas. John must have felt a heavy sense of responsibility. Each step of the way was carefully planned.4

Beeman's horse-drawn wagon train entered Texas on December 6, 1840, crossing the Red River from Arkansas into Bowie County. Some of the Illinois emigrants continued west, but the Beemans laid over in Bowie County for a year. All three Beeman women were pregnant.5 While waiting delivery of the children, the men rented land near Dalby Springs in the extreme southwestern corner of Bowie County and planted a spring corn crop. During the summer and fall of 1841, Northeast Texans were called up to fight Indians along the Trinity River. The Beeman family heads enlisted in the militia, seizing the opportunity to reconnoiter the Three Forks country. After the Village Creek campaigns drove Indians from the Three Forks area, militia leader Jonathan Bird was authorized to establish a fort on the West Fork of the Trinity River. The Beemans were ready to venture farther west.6

Bird's Fort, a picketed stockade with blockhouse and cabins (near present-day Arlington), was a short-lived settlement on the edge of the Texas frontier in 1841. The militiamen constructed cabins and a stockade; then some, including John Beeman, went back to Northeast Texas to harvest crops. Returning with their families, the Beeman wagons rolled across the prairie to Pin Hook (near Paris). At Honey Grove, they swapped the horses for oxen which were less attractive to Indian raiders. On reaching Ft. Inglish (Bonham) they were met by Major Bird, who informed them of desperate conditions at the fort. John Beeman personally paid for cattle and corn to resupply Bird's Fort. By the time Beeman's party arrived in November 1841, the soldiers were starving. The Republic of Texas failed to send promised supplies; efforts at farming also failed. Their exposed location, the nearby malarial lake, the death of Hamp Rattan at the hands of Indians, and (finally) news that the land had been granted to the Peters Company of Kentucky, led to abandonment of the fort.7

The Beemans and others remained at Bird's Fort through the winter of 1841-42. Despite hardship, they remained optimistic. John S. Beeman wrote to Illinois relatives, "if you would come to Texas—you could have land enough to do you all." He pictured plenty of grass, a healthy climate, and good water, promising "you could raise sweet potatoes in the bottom land8 James J. recalled how, despite bitter cold and a six-inch December snowfall, the men cut the first wagon road across the Elm Fork of the Trinity to Ft. Inglish. Solomon Silkwood (Beeman's brother-in-law) died of exposure. Beeman's appeal to "come to Texas, for good land and weather" was not altogether candid considering the desperate conditions. The Bird's Fort experience would linger in John Beeman's memory for years as he led an effort to get veterans reimbursed for expenses, loss of land, and military service in 1841-42.9

Venturer and erstwhile Indian trader John Neely Bryan visited the fort in January 1842, inviting the militia and settlers to move to his location, closer to settlements and resupply.10 After a trip to look the country over, the Beemans and a few others decided to fall back 22 miles east to the area Bryan was calling "Dallas11" Mabel Gilbert, a former riverboat captain, chose to send his pregnant wife by raft down the West Fork while the Beemans took the land route. On arrival, Gilbert had a cabin built on Bryan's bluff and farmed the bottomland west of the river.12 In early April 1842, the Beeman wagons crossed the Elm Fork of the Trinity River and "nooned" at a stream they called "Turtle Creek." Following an Indian trail and by-passing Bryan's location, they camped that evening in a post oak grove near present-day Peak and Worth streets. The next day, April 4, 1842, they reached White Rock Creek.

John Beeman chose a beautiful spot above the creek for his homestead. It was at a major crossing of the creek which he recognized as a prime location for either a ferry or a bridge.13 Beeman believed his claim to be outside the Peters Colony grant.14 Soon after his arrival, he rode north to Mustang (Farmers) Branch, headquarters of the Peters Company agent, to check his location and pick up mail from Illinois. On the frontier, the rare letter was eagerly anticipated. Settlers were hungry to get news from home.15 Despite urging from Texas, Illinois relatives were not all convinced to emigrate. One Illinois Beeman responded, "we'd rather 'dye' her [sic] with a sick 'stumake' than go to 'texis' with a hungry belly."16 In 1846, John's brother Samuel and family emigrated, bringing with them Emily's young brother, William C. Hunnicutt, and his family; but the rest of the Beemans stayed in Illinois.

On his return ride from the Peters Colony agency, John encountered a band of Indians near what is now St. Matthews Cathedral (Ross at Henderson streets). Chased by the Indians, John lost his hat and two letters but outran his pursuers on his fast horse. The next day, his fifteen-year-old son, William, retrieved the hat and letters. With hostile Indians about, the Beemans barricaded themselves behind their wagons, kept a bonfire going all night, and shortly thereafter began construction of a sturdy blockhouse.

The Beeman Blockhouse was a two-story cedar log structure, fifteen feet square with the second-floor loft overhanging its lower walls, featuring gun ports for firing at hostiles. During the time of its occupation, several trips were made back and forth to the East Texas settlements for safety and supplies. The women and children were sometimes left alone when the men went hunting or back to the settlements. One story tells of Emily Beeman and the girls dressing broomsticks in men's hats and marching them about to impress lurking Indians. Although Indian signs were seen, the blockhouse was never attacked. Had it been, Emily was said to be as good a shot as any man.17

Over the years, the Beeman Blockhouse, the only such structure in Dallas County, was a safe haven for family and visitors. In July 1843, Sam Houston's party, en route to parlay with Indians at the Three Forks, camped on Beeman land near the Big Spring. Then it stopped by the blockhouse, where Edward Parkinson's diary recalls they were welcomed with spring-cooled buttermilk. Houston moved on to Bird's Fort via Cedar Springs, guided by James J. Beeman, but Parkinson stayed overnight, and John H. Reagan, Houston's former guide, lingered to recover from typhoid. In 1845, Peters Company agents Charles Hensley and John C. McCoy called on the Beeman blockhouse. It was a popular way station for passing travelers.18

Near the blockhouse, at present-day Dolphin Road and South Haskell St., John Beeman built a double log cabin later described by his great grandson Mark Beeman: "Our people camped down near the river for a while but mosquitos were so bad ... John Beeman moved his family out on high ground and built a log cabin. ... My Grandfather W.H. Beeman went with his father to Shreveport and ... (it took them) 18 months to (haul) ... lumber (pine and cypress). They had 4 teams of oxen and my grandfather was an expert oxen driver as he was outstanding in handling the bullwhip." Mark Beeman recalled how he played in the old Beeman cabin as a child." ... it had rifle loops and in damp weather there were dark spots on the floor and walls that the old people said were blood stains."19 The Beeman Cemetery, the oldest in Dallas County (1845), is located near the old homeplace.20

William Hunnicutt Beeman, John's teenage son, planted the first corn crop in Dallas County. His first planting of corn, peas, and pumpkins was accomplished with a homemade plow fashioned from a tree fork. Buffalo trampled and ate the corn but spared the pumpkins. Corn was the staple of the Beeman diet. There was hominy, grits, corn dodger, even coffee made of corn. The corn was ground on a steel millstone brought from East Texas. Wild meat was plentiful—deer, turkey, squirrel, sometimes bear and buffalo and fish from the creek. Flour and sugar were scarce, but honey sweetened their cornbread. William recalled attending a wedding at neighbor Judge Thomas's where real pound cake made with flour and sugar was the highlight. As to clothing in those early years, the women spun cotton for shirts and the men fashioned vests, pants, and moccasins of deerskin.21

William Beeman was an enterprising young man who also helped build the first ferry across the Trinity River at Bryan's Bluff, where his older sister Margaret lived with her new husband John Neely Bryan. The ferry consisted of three large cottonwood logs, dug out like canoes, covered with cedar planking (puncheon flooring), the tow ropes of twisted buffalo hair.22 In all of their endeavors, the Beemans acted out of their experience on the Illinois frontier, cutting roads, opening a ferry, building a blockhouse, and milling corn. By marrying Margaret Beeman, Bryan became a member of the formidable Beeman clan and benefited from their skills.23

Bryan proved to be an enthusiastic land promoter, laying out and selling lots to newcomers attracted to Dallas. John Beeman, ten years Bryan's senior, was an equal partner in the development of the town. He was instrumental in Dallas becoming a county with Bryan's town its county seat. John Beeman rode alone from Dallas to Austin in 1846 to the first legislature of the new State of Texas, seeking to have Dallas declared a county. When the legislature refused to seat him since he came from a nonexistent county, the Robertson County representative put Beeman's petition before the legislature. Son William made the risky journey to Franklin in Robertson County to pick up the papers creating Dallas County.24 John Beeman shared Bryan's vision of a navigable Trinity River, attempting with his son-in-law to burn two miles of driftwood which blocked the stream. He purchased land west of the Trinity, across from Bryan's, so that the family controlled both banks at the ferry landing.25

John Beeman probably deplored his son-in-law's business practices. Too often, Bryan gave away town lots rather than selling them. He made the ferry free to attract more traffic. By 1850, Bryan's behavior was increasingly erratic. Like most Dallas men (including William and James J. Beeman), he went to the California gold fields.26 On his return, he was drinking heavily and seemed to have lost interest in the town. In 1851, he was indicted for Assault with Intent to Commit Murder, but when the district court finally met, he pled guilty to a lesser charge and was fined $127 Dogged by legal problems, in 1852, Bryan sold his remaining interest in Dallas, including the ferry rights, to his ambitious friend Alex Cockrell. In 1855, thinking he had killed a man, Bryan fled Dallas, absenting himself for several years. Margaret Beeman, on her own with her small children, would have been in dire straits without the support of her family and Sarah Horton Cockrell.28

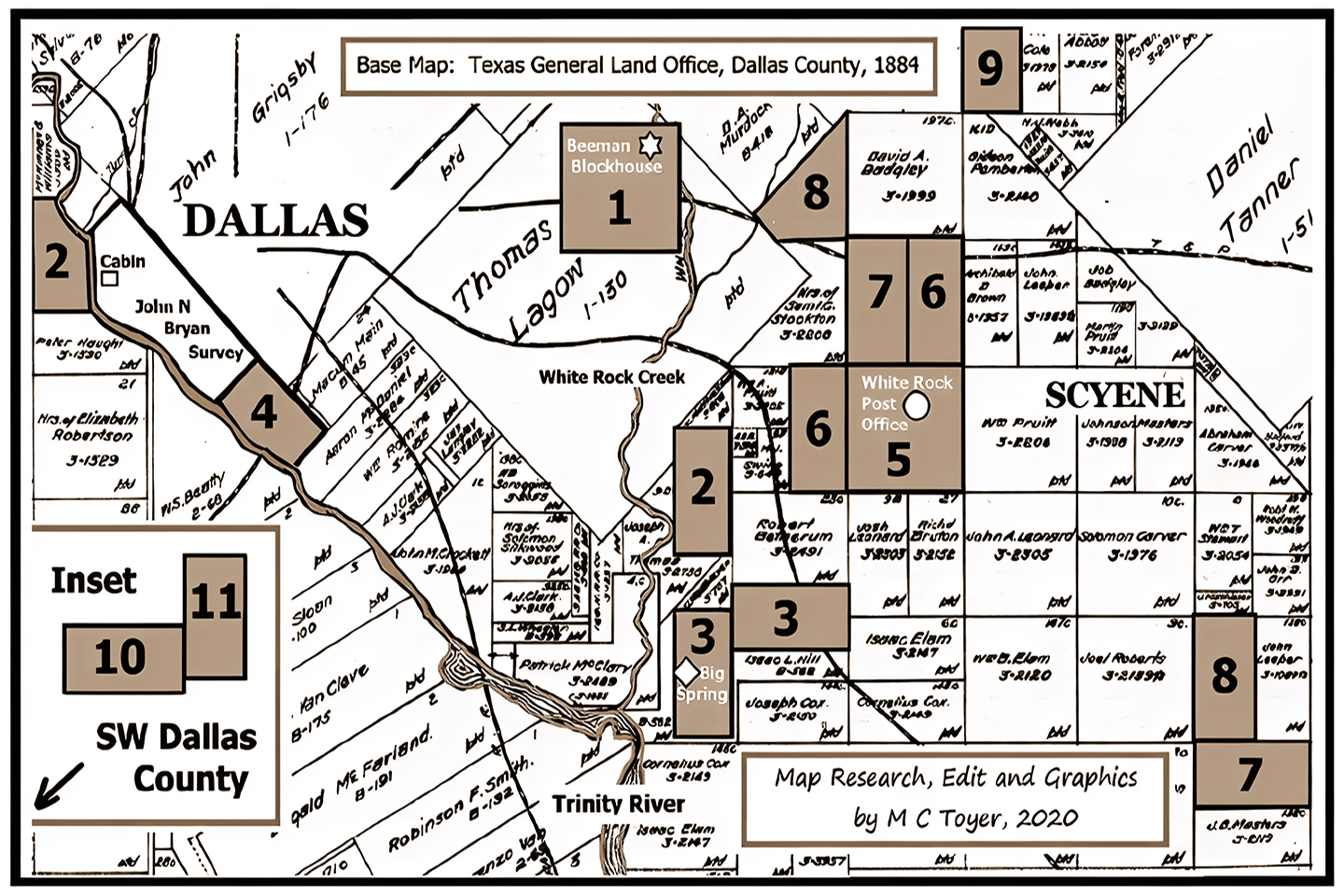

In sharp contrast to Bryan, John Beeman systematically acquired land in strategic locations of east Dallas County. When he learned that his homestead lay in the earlier surveyed Thomas Lagow grant, he bought land on both sides of White Rock Creek from that family. On finding that his land was part of an extended Peters Company grant, he persisted in petitioning the legislature until they granted him title. He also vouched for Bryan's shaky land claim.29 In addition to his lands west, south, and east of Bryan's location, Beeman used his headright grant and the balance of his Toby scrip to acquire the Cedar Brake, the Prairie, and the Big Spring tracts—land suited to provide timber, grazing, and water.

John Beeman was a successful Texas farmer and stockman. He grew wheat and rye and grazed cattle in the Trinity bottomland. At his farm was a shop where he made almost anything needed by early settlers and taught his sons the skills of the wheelwright, blacksmith, and wagon maker. Beeman was also Dallas's first banker: he frequently loaned money or co-signed his neighbors' notes so that they could borrow. Family and neighbors sought his advice.30 When John Beeman died in 1856 at age 57, he had accumulated a sizable estate to provide for his wife and ten surviving children.31 A newspaper reporting his death noted that John Beeman was the "first family man to move to Dallas Co. who was to remain." A contemporary stated that Beeman "lived greatly respected, died lamented."32 His sons, William and Scott Beeman, continued to play an important role in Dallas development.

Any study of early Dallas history finds sources problematic. John Beeman was a man of deeds, not words. He kept no journal and left no letters.33 His half-brother, James Jackson Beeman, did write important memoirs which paint a vivid picture of life in the early settlement. Some said that James cast his deeds overlarge when, in fact, the Beemans did things together rather than single-handedly. There are four enlightening interviews with John's son, William H. Beeman, given around the turn of the twentieth century after memories had dimmed and deeds were perhaps exaggerated. Scott Beeman was interviewed in 1927 when he too was elderly; some of what he recalled was second-hand as he was only a child during the early Dallas years. A portion of this study relies on material about the Beeman family collected by Ruth Cooper, who researched the Beemans for forty years. Ruth's source of rich family lore was her grandmother, Sonoma Beeman Myers, daughter of William H. Beeman, who lived with Ruth and her mother for many years.34 Charles A. Beeman, son of James J., and Mark Beeman, grandson of William, also added to the paper record.

All of the above would agree that the Beemans have been denied the recognition they deserve for their essential role in the settlement of Dallas. While conventional wisdom attributes the origins of Dallas to John Neely Bryan, Bryan's partnership with John Beeman was a key factor in the success of the settlement at the Three Forks. Bryan might have been the visionary promoter of the settlement, but Beeman gave it substance. Bryan was enthusiastic, impulsive, mercurial; Beeman was steady, responsible, dependable. Perhaps it required both types of personality to build a town in the wilderness.