Fighting for Bird's Fort

Arlington Citizen-Journal, February 16, 1997

by Robert Cadwallader

Historians, others fear for future of Metroplex's birthplace

Bird's took a bold stab against the wild and dangerous West.

Its founders in 1841 were few in number and ill-supplied, but in their brief battle against the elements and the Indians—and ultimately a competing settlement—a population took root in its protective shadow.

Its legacy, say many historians, is no less than the Metroplex itself.

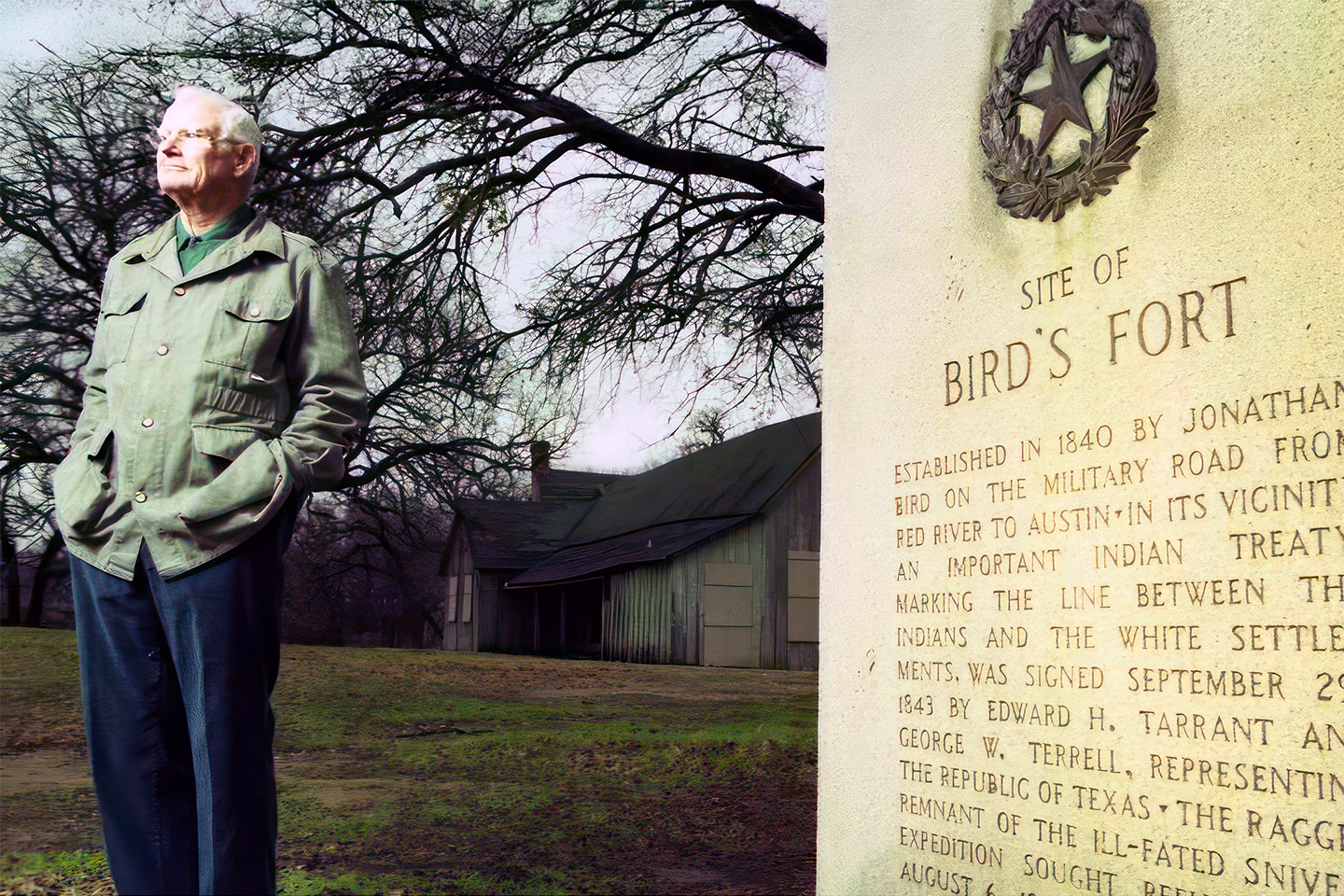

But today, all that remains of Bird's Fort is a stern granite marker, nestled beneath a windmill near the northeast tip of Arlington.

And some worry that even that meager remnant may some day fall victim to the fort's own creation.

"It just seems like it's being swallowed up," said Jann Cunningham, the great-great-great-granddaughter of Jonathan Bird, the man commissioned to establish the fort.

The swell of economic growth in the area breathes heavily on the quiet, 111 acres of privately-owned property where the marker sits. A 2,000-acre upscale housing-retail development surrounding that property is scheduled to begin soon.

Cunningham, who lives in Oklahoma, and other descendants, as well as several local historians, are asking for solutions.

"If we could just be assured that that one little spot would be preserved," Cunningham said.

Bird's Fort was conceived by Jonathan Bird, who was fresh from fighting Indians at the Battle of Village Creek, near present-day Lake Arlington. Armed with the temporary title of brevet major, bestowed on him by the Texas Militia, he took a band of 40 men and built a log stockade, a block house and a few cabins near the 23-acre lake, Calloway Lake—sometimes called Silver Lake—about a mile north of the Trinity River and a mile east of what is now Farm Road 157.

It was a hard winter, and the Indians had no intention of retreating without a fight. At least five settlers were killed, according to historical accounts. Their burial sites near the fort were eliminated years ago when the area was excavated for sand and gravel.

Before long, the fort faced another enemy—attrition among settlers. With the nearby Peters Colony receiving authorization to extend to the south; many Bird's Fort residents moved out, soon forcing the post to close.

Still, the fort's brief life spun the thread by which the history of the Metroplex can be traced.

In the midst of the post's hard winter, a young man named John Neely Bryan coaxed several of the settlers to move with him to a frontier to the east. Some built rafts from cottonwood logs and floated down the Trinity River to the site, which marked the birthplace of Dallas.

Then, nearly two years after the fort disbanded, its name became forever associated with one of the great Indian treaties in Texas history. Military leaders and the grand council of North Central Texas Indian tribes established a respected line between the Indians' and white man's land. It was named the Bird's Fort Treaty.

"It was the most sweeping Indian treaty ever negotiated by the Republic of Texas," said Ron Wright, vice chairman of the Tarrant County Historical Commission, who writes a column for the Arlington Star-Telegram. "It opened up all of North Central Texas for settlement."

The treaty called for the establishment of trading posts along the boundary line. The first was at the present-day Founders Park in Arlington in 1845. The next year, Col. Middleton Tate Johnson set up the nearby Texas Ranger post that spawned Johnson Station, which became Arlington.

When Maj. Ripley Arnold came to the Arlington area to establish a fort in 1849, Johnson, whom historians call the "father of Tarrant County," escorted him to a site he liked at the confluence of the Clear Fork and West Fork of the Trinity. The settlement became Fort Worth.

"You had a continuum of events that sprang from Bird's Fort," Wright said. "All of these things are connected from the founding of Dallas, Arlington and Fort Worth. It's like a birthplace. It was the first Anglo settlement in this area."

During the Texas Centennial, in 1936, the state placed a large, tombstone-shaped granite marker at the site of Bird's Fort to commemorate the fort's place in history. It was one of only three places in Tarrant County—all in Arlington—to receive one.

In the 61 years since, the monument's dark gray has turned nearly white. Now decorated with rocks around its base, it is the only remnant of a compound long since stripped by settlers seeking wood to build their homes.

The land for The Lakes of Arlington housing development that surrounds it is planned for annexation, pending a City Council vote on Tuesday.

Although the 111 acres where the marker rests would continue to be a buffer, several history enthusiasts and Bird descendants aren't satisfied. They want the city to annex at least enough of the marker's surroundings to carve out a small city park that would preserve the history.

"There's really not much to preserve other than the site itself," said Dorothy Rencurrel, who is chairwoman of the Landmark Preservation Committee and serves on the Tarrant County Historical Commission. "But I would hate to see them bulldoze the little mound of rocks we have out there now, where the fort stood. Unless we can convince the proper authorities not to let that happen, it will."

Not all believe annexation is the best route. Cliff Mycoskie, a co-owner of the Silver Lake Gun Club, which leases the property for skeet shooting and target practice, bristles at such talk.

"Do they lease the property? They need to mind their own business," said Mycoskie, the former chairman of the Arlington Planning and Zoning Commission. "I would think that we would be the best friend to them. We're going to preserve it the way it is. We're preserving it to be used for what it has been since mankind has had it."

The land, which has been leased by a series of sportsman clubs for more than a century, is owned by Charles Armentrout. His father and four other men bought it in 1917. Armentrout's father bought out the others in 1939.

The 82-year-old University Park resident said that the gun club still has 10 years on its lease and that he has no intentions of selling it afterward. But he said he is arranging to deed the property over to his children.

Might they sell it?

"Not as long as I'm alive, they wouldn't," Armentrout said. "But after I'm no longer a member of society, there's no telling what might happen."

That only fuels the uncertainty among those who worry that the land could wind up in the hands of a developer with little sense of history.

The issue of annexing the fort site came up as the city of Arlington negotiated the annexation of The Lakes of Arlington land being developed by Metrovest Partners Ltd. But it was not considered because it would have only complicated the process, officials said.

Mayor Richard Greene said last week that he still thinks annexation should be considered separately, after the Metrovest deal is done, as a means of giving the city tighter controls on the site.

"Our approach is not necessarily to force the city's jurisdiction on property owners who don't want it," he said. "But at the same time, that's a historically important piece of property."

Armentrout had a brief response.

"I understand that Greene fellow's not going to be around there," he said, referring to the announcement Wednesday that Greene would not run for reelection.

Caroline Ingram of San Antonio, one of Bird's direct descendants, said she wishes for more than preservation. She wants Bird's Fort to receive its due respect in mainstream history education.

"He's not in the Texas history books," said Ingram, who has never visited the marker. "I never heard of him until I was grown."

The site already serves as an educational tool for Treetops School International, a private school in Euless where students visit the site and learn about the early settlers. School director Chris Kallstrom said she wants it to be there for generations to come.

"We're an international school, and we travel a lot. And in all of those places, there are constant evidences of the past," she said. "There are very few evidences of the past in our area."