Indians Before and After the Arrival of White Settlers

Book Excerpt (Chapter III) from A History of Collin County, Texas

by J. Lee Stambaugh & Lillian J. Stambaugh

Dr. E. H. Sellards, director of the University of Texas Memorial Museum, estimates the antiquity of man in Texas at 100,000 years. When the white man came to the Southwest, this section was probably one of the most thickly settled areas of North America. A mild climate, coupled with a plentiful supply of buffalo, deer, cattle, and other wild animals, fish, native fruits, berries, and nuts, enabled the inhabitants to live easily.

There were three Indian eras in Texas: (1) those who left before the white man came, (2) those living here when the white man came, and (3) Indians driven west by migration of the pioneer white man's advance westward from the Atlantic coast.

The most important Indians living in Texas from 1690 to 1730 were the Caddo tribes. This great family was broken into three divisions: (1) the Hasinai Confederacy in the lower half of the Texas pine belt, (2) the Caddo proper group in northeast Texas, and (3) the Wichita group, occupying the Red River Valley and the headwaters of the Trinity River.11Texas Almanac, 1941-1942 (Dallas, 1940), pp. 37-40.

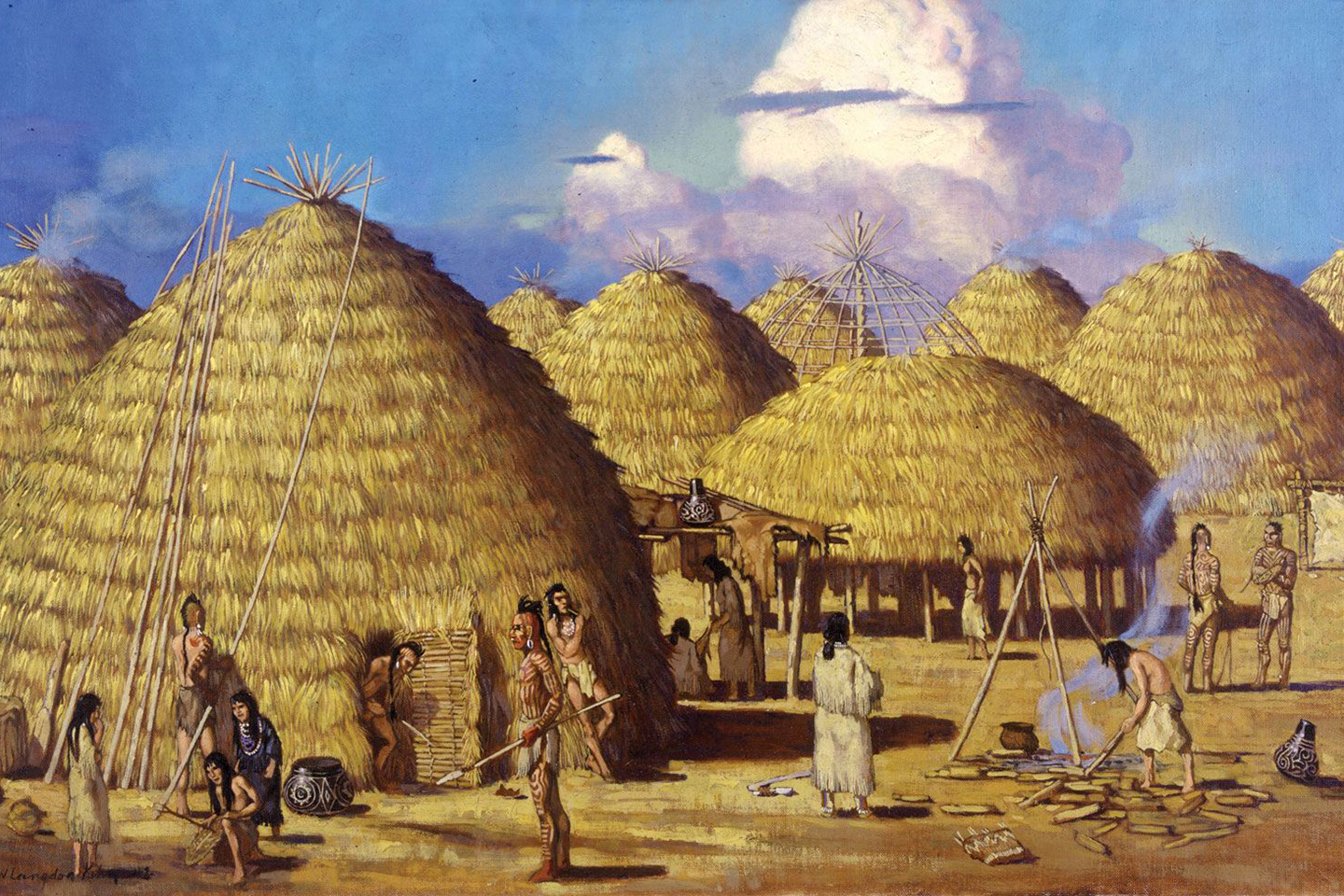

The life of the Caddoes was centered around permanent settlements of substantially built grass houses, some of which were as large as fifty feet in diameter. They were constructed by placing posts upright in a circle, forming a wall about five feet high. The conical roof consisted of a framework of rafters and cross beams, securely lashed together and covered with grass overlapping like shingles. These buildings were thus quite spacious, being twenty to thirty feet in height. The Caddo Indians venerated fire, erecting temples in which a perpetual flame was kept burning. They had a well-developed sign language. Other tribes knew them as "Pierced Nose" because of their habit of wearing metal rings in the nose and in the earlobes. They painted and scarified their faces and breasts. The men wore fine deerskin shirts and breechcloths and the women wore skirts of the same material. Both sexes wore leggings and moccasins of deer and bison hide. They welcomed travelers and strangers and were friendly at all times.

The Caddo Indians depended principally on agriculture for a liveli-hood, supplemented by fishing and hunting. They grew pumpkins, sun-flowers, tobacco, five varieties of beans, two crops of corn a year, and had orchards of peach, plum, and fig trees. Salt and bow wood were trade items. The men helped the women in the fields and did the hunting.22A. D. Krieger, "Caddo Indians," Handbook of Texas (Austin, 1952), I, 264-266.

The Wichita branch of the Caddo Indians continued to live between the upper Brazos and Trinity rivers until 1855 when they were placed on the Brazos Indian Reservation. Later they were transferred to Oklahoma.33Margery H. Krieger, "Wichita Indians," ibid., II, 905.

The Comanches of the upper Panhandle were a fierce nomadic tribe who became expert horsemen and daring warriors. They drove the Lipan Apaches southward and the Wichitas eastward and by 1750 had established themselves as far east as the Blackland Prairies and as far south as San Antonio.

There is no way of determining the exact Indian population in Texas in about 1750 but it has been estimated at 30,000. Tribal boundaries shifted rapidly and often. White pioneers in their westward advance from the Atlantic seaboard gradually drove the Cherokees, Alabamas, Coushattas, Seminoles, Delawares, and the Kickapoos into Texas.44Texas Almanac, 1941-1942, pp. 37-40.

Indians living in the vicinity of Collin, Dallas, Hunt, and Grayson counties were not, as a rule, hostile toward white people. The following attacks which were made on settlers from 1840 to 1850 were blamed on the Comanches, who made raids from the west and later retreated in that direction.

Late in November, 1841, a wagon was sent from Bird's Fort, in present Tarrant County and twenty-two miles west of present Dallas, to the Red River for provisions. When the scheduled time for its return had passed, A. W. Webb, S. Silkwood, and Hamp Rattan were sent to investigate. On Christmas Day, while these men were cutting down a tree on the east side of Elm Fork, one and a half miles southwest of where Carrollton is now located, they were attacked by Indians and Hamp Rattan was killed. After killing one of the savages the other two men fled back to the fort, where Silkwood soon died from exposure. A single man, then dispatched to find the relief wagon, succeeded and on December 30 the party reached the scene of the killing. Here the members found Rattan's faithful dog still guarding his body. On May 22, 1841, John and Liddleton Rattan, two of his brothers, were in the fight at Village Creek, six miles east of the present site of Ft. Worth, when Captain John B. Denton was killed. Hamp Rattan was the son of Thomas Rattan who came to the present Melissa in 1844. Other children of Thomas Rattan who came to Texas were Mrs. Hogan Witt, Mrs. J. W. Throckmorton, Mrs. John Kincaid, Mrs. William Fitzhugh, and T. H. Rattan.55John Henry Brown, History of Dallas County from 1837 to 1887 (Dallas, 1887), p. 11; Wilson, Book 8, pp. 3, 4.

In November, 1842, J. H. Wilcox, David Helms, and Joseph Harlan attempted to found a settlement on Wilson Creek, but this was broken up by Indians so the group joined John McGarrah in establishing Buckner.

Just prior to November, 1842, Wesley Clements, Samuel Young, and a man named Whisler with their families settled three miles north of McKinney on Honey Creek. Late in December, Young went to Fort Inglish in Fannin County to get supplies. On Christmas morning, while working in the timber near their cabins, Clements and Whisler were attacked by Indians and the latter was instantly killed. Clements fled toward the cabins. His wife, hearing the commotion and seeing her fleeing husband, rushed to meet him with his gun in her hands. She was, however, too late. He was tomahawked and scalped within fifty yards of his home. With the aid of Mrs. Young, Mrs. Clements barred the door and kept the Indians away with the gun. In the meantime, Mrs. Whisler, who was at the branch, heard the firing and saw the Indians. She submerged herself in the stream, keeping only her nose above the water, until all was quiet. Believing that all members of her own settlement had been killed, she hurried down the creek toward Fort Inglish. To her the experience was particularly horrible, since her parents had previously been killed by Indians on the Brazos. Finding East Fork too deep to ford, she continued downstream until she reached a place shallow enough to permit her to cross. Again she returned to the road leading across open prairie toward Fort Inglish. Her clothing was torn to shreds and her body bleeding. When two men in a wagon approached, she detoured around them. They called to her but she only quickened her pace, explaining that Indians had killed all in her settlement. When she refused their help, only running still faster, they concluded that she was deranged. Upon reaching Honey Creek, these men saw Mrs. Clements and Mrs. Young on the opposite bank. The stream was so swollen that the men were forced to fell trees to enable the women to cross it. Then all retreated to Fort Inglish. Clements and Whisler were buried in Throckmorton cemetery. This tragedy occurred on the first anniversary of the murder of Hamp Rattan, near Carrollton. It also took place while an important event in Texas history was happening - the Battle of Mier.

In February, 1843, while John McGarrah, J. H. Wilcox, David Helms, Joseph Harlan, a Mr. Blankenship, and William Rice were erecting cabins at Buckner, Dr. Calder, who had settled at Cedar Springs (now Dallas, arrived, riding a horse and leading another, en route to Fort Inglish. Soon after leaving he was seen running back toward the house on foot pursued by two Indians. The men rushed to the rescue but Calder was slain and scalped before they could reach him. At the same time the relief party was attacked by about sixty Indians, who suddenly arose from tall grass, armed with guns and bows and arrows. The white men retreated to the unfinished house and drove the savages away. Later it was found that Dr. Calder had killed one of his assailants with the load from one barrel of his shotgun. This gun was then a new invention, unfamiliar to the savages, who had left it where they found it with one barrel still loaded. Dr. Calder also lies buried in Throckmorton cemetery.66McKinney Advocate, April 3, 1880; John Henry Brown, History of Dallas County, pp. 37-50; J. M. Muse in a speech before the McKinney Rotary Club, May 3, 1933, found in Wilson, Book 34, p. 107.

About 1844 Indians raided in the communities about three miles east of McKinney, so Peter Fisher took his family to the old fort on Red River for safety. Upon his return he learned that two of the Alred boys had been killed by Indians. The Alred family had come to Texas with the Fisher family.77George Pearis Brown, former county attorney of Collin County and assistant United States district attorney, son of Robert H. Brown, an early Collin County settler, made a valuable collection of history of his native county. About 1931 he and his secretary traveled over the county, interviewing pioneers. These more than 300 pages of recorded interviews became his "Scrapbook of Traditions, Annals, and History of Collin County from 1846 to 1880" All this material is in the possession of his daughter, Miss Esther Russell Brown, of El Paso, Texas, who made it available to the writers. It will be referred to as "MS., Brown Papers." — D. B. Fisher in MS., Brown Papers, p. 161.

The last of the fatal depredations made by Indians in Collin County occurred in the fall of 1844. Jeremiah Muncey, with his wife and four children and McBain Jameson, had settled on Rowlett Creek, about four miles north of the site of Plano, and were living in a board hut while their log house was being built. One day Leonard Searcy and his son Gallatin (or Thrashly), who lived near present Walnut Grove, and William Rice and son from near the present Foote, went on a hunting trip down Rowlett Creek. After pitching camp, Searcy rode down to the Muncey hut. Here he was shocked at what he discovered. Muncey, his wife, Jameson, and the three-year-old child had been murdered that morning by Indians. Mrs. Muncey's body was badly mutilated and the child's head had been crushed into a shapeless mass. The fifteen-year-old Muncey boy had gone to the Throckmorton settlement and thus escaped death. The two other boys, twelve and seventeen years of age, were missing and were never heard from again. Later discoveries revealed that they had been killed by their captors as they retreated westward.

Searcy hastened to report to Rice. Their sons were out hunting and the frightened fathers went in search of them. They soon came upon the mutilated body of young Rice, which they put on one of their horses, and continued to search for young Searcy. He was found alive on Wilson Creek, ten miles away. After seeing young Rice killed, Searcy escaped and was trying to get help for the two fathers.88McKinney Advocate,, April 3, 1880; MS., Brown Papers, pp. 313-314; John Henry Brown, History of Dallas County, pp. 41, 42.

The site of this massacre can now be definitely located. "Indian Hole," which takes its name from this incident, is a deep waterhole at a sharp turn in Rowlett Creek about 300 or 400 yards downstream from the bridge on U.S. Highway 75. Mrs. J. H. Hagy and daughter, Geraldine, own and live on the farm located on the right side of Rowlett Creek. This land includes the Muncey homesite. Muncey Spring is 200 or 300 yards north of the Hagy home while the cabin site is about 200 yards northwest of the spring. Jameson and the Munceys were buried near the creek beneath three sycamore trees only a few hundred feet from where they were killed. A large oak tree marked the site of this massacre until a few years ago when some hunters set it on fire while smoking a rabbit from the hollow in it. The Hagys have placed a cedar post where the old tree stood. It is hoped that some day the people of Collin County will erect here a permanent memorial to the memory of these brave pioneers.99A visit to the site and an interview with Miss Geraldine Hagy, May 15, 1956.

Also during 1844 Indians came to the home of Thomas J. McDonald, three miles from McKinney on the Weston Road. The family was spending the day with friends so did not learn of the visit of the red men until they returned home and found that their featherbeds had been emptied in the yard and along the road and their house badly damaged but still standing.1010J. M. Muse in Wilson, Book 34, p.107.

There are also other reports of Indians in Collin County after 1844. Perry Mugg, who came to the Weston community with his parents in 1848, reports having seen deer, buffalo, and Indians near their home one mile northeast of Weston.11 Mrs. W. B. Flanery, who came to Texas with her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Stewart, in 1851, stated, "It was not safe to go very far from home on account of Indians.1211McKinney Examiner, July 10, 1930.12Manuscript in the possession of the writers.

All association with the Indians, however, was not tragic. There is an account of Frank House, a Chickasaw, who came to McKinney in 1841 and continued to live there until in the 1920s. He was peaceful, industrious, and highly respected.1313Wilson, Book 14, p. I.

Indians have often been accused of atrocities which were committed by others. The following is an effort to correct one of these injustices. At least four publications have stated that Christian Stelzer was killed by Indians at his home, two miles east of Celina, on April 2, 1862. Three of his grandchildren state that this is not true. The late John T. Mallone of Celina gave in substance the following information in the George P. Brown Papers: "Dr. James Marshall, physician, teacher, and preacher of Cottage Hill, attended the father of Abiel Stelzer when he was wounded with a knife and killed at his home by Judge Tenny during the War between the States." It seems that the trouble started over a trivial matter. A stone now marks the grave of Stelzer, who was buried where he was wounded, one-half mile south of Cross Roads cemetery. His son, Abiel, enlisted in the Confederate Army on May 18, 1862, when he was seventeen years of age, and was honorably discharged in May, 1865.1414MS., Brown Papers, pp. 118-120; Interviews with Mrs. Mary Stelzer-Moore, August 6, 1955 and Mrs. Alice Stelzer-Glendenning and Fred Stelzer, September 4, 1955 — all grandchildren of Christian Stelzer.