Calloway Lake and the Fort Before Fort Worth

Hometown by Handlebar, January 30, 2023

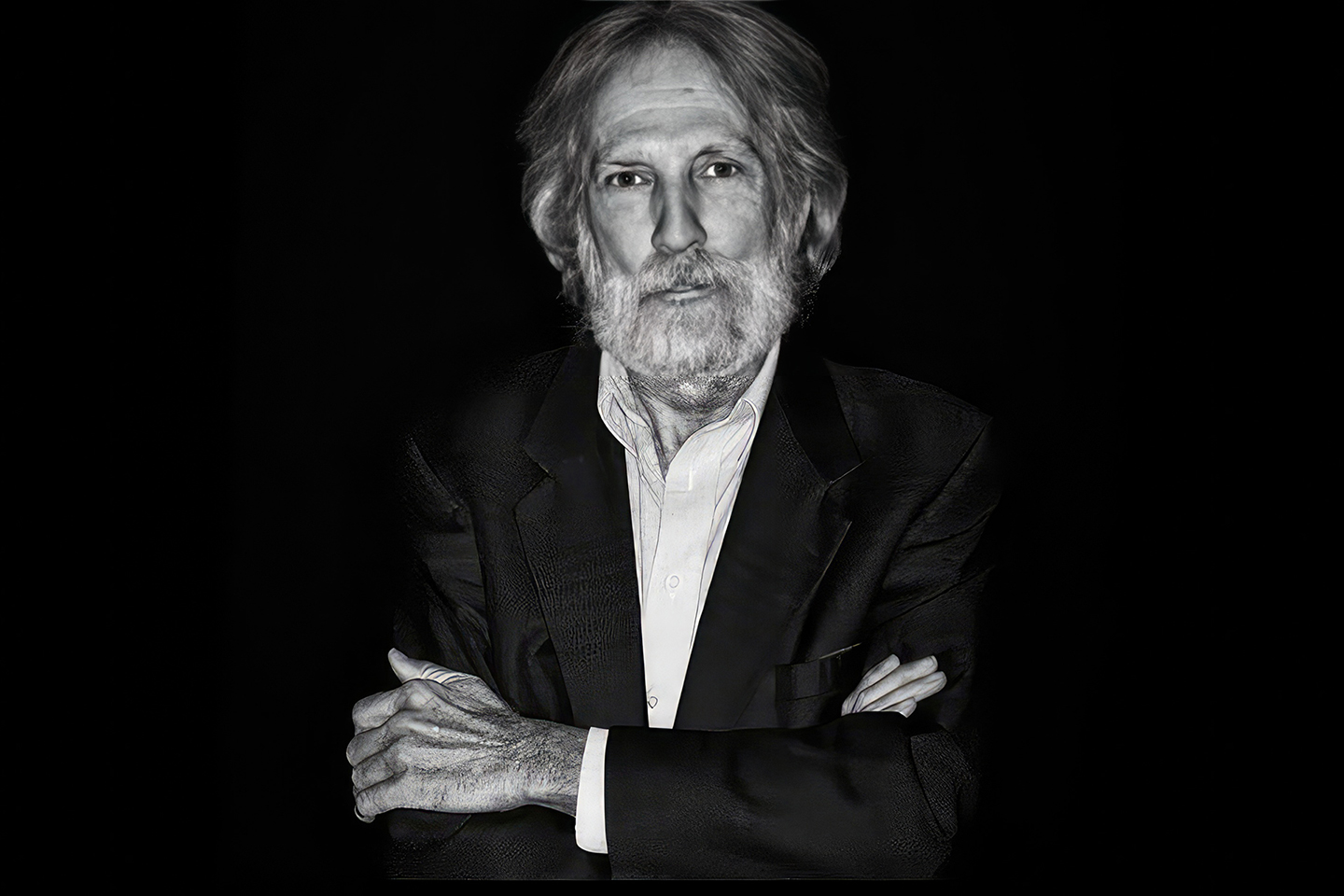

Author and journalist Mike Nichols' blog, Hometown by Handlebar, has long been one of DFW armchair historians' best kept secrets. Based in Fort Worth, Mike's musings often found him venturing out to surrounding cities.

Mike died in August of 2023 of cancer complications, but the 2,000 posts and 1.1 million words that he left behind in his blog are a treasure trove of well-researched articles on lesser-known DFW history.

Some historic sites demand to be given the attention they deserve. They stand up straight with chest out and feet planted squarely. They shout their story. Other historic sites are self-effacing. They slouch with hands in pockets, eyes to the ground, toe in the sand. They whisper their story.

Calloway Lake in north Arlington is one such whisperer. It whispers its story in the rustling of the leaves of the cottonwood trees that encircle it and obscure it from our view, in the gurgle of shallow water as Hurricane Creek feeds the lake on one end and drains it on the other, in the “plink” heard as a frog on the shore, startled by the approach of a rare visitor, dives with scarcely a ripple into the water.

Don’t let Calloway Lake’s modesty deceive you.

Calloway Lake’s whispers tell us of the first white settlers in Tarrant County, of the “there goes the neighborhood” resentment of long-resident Native Americans, of death in the snow on a Christmas Day, of General Edward H. Tarrant and President Sam Houston and John Neely Bryan and a nascent settlement to the east called “Dallas.”

Few points in history can be traced to a single, “big bang” beginning. But we can begin the story of Calloway Lake and the fort before Fort Worth on May 24, 1841 a few miles to the southwest on Village Creek. At that time and place General Edward H. Tarrant of the Republic of Texas militia led seventy volunteers from counties along the Red River in a punitive raid on Tonkawa, Caddo, and Cherokee living in a string of villages along the creek. Early on May 24 the soldiers attacked the southernmost village at the site of today’s Arlington Lake. The soldiers encountered only light opposition as they captured the village, in part because many braves were away on a buffalo hunt at the time. Some soldiers rode off in pursuit of Native Americans who had fled the village. Tarrant and other soldiers remained behind at the captured village. Captains James Bourland, John Bunyan Denton, and Henry Stout led scouts north along the creek, encountering increasingly larger villages and heavier resistance as they traveled. In a running gun battle south of the Trinity River Native American gunfire injured Henry Stout and Captain John Griffin. Methodist circuit rider/Native American fighter John Bunyan Denton was shot and killed—the only white fatality. Among the Native Americans a dozen were killed and many more injured.

In response to the resistance met that day at the Battle of Village Creek, General Tarrant ordered a fort built in the area to protect current white settlers and to encourage new white settlers. Tarrant brevetted Jonathan Bird of Bowie County to the rank of major and assigned him to build and garrison the fort. Bird was born in Tennessee in 1783. By October 1841 about forty volunteers of the Fourth Brigade of the Texas militia—Bird’s company and Captain Alexander W. Webb’s company—had built a log blockhouse surrounded by trenches and a few outbuildings enclosed in a picket stockade. The fort was located on the north side of Calloway Lake. The crescent-shaped lake provided protection from attack from the south. A few settlers, including the families of some of the volunteers such as Wade Hampton Rattan, soon arrived from Lamar, Bowie, and Red River counties. This was the first white settlement in Tarrant County. In fact, Governor James Webb Throckmorton said Bird’s Fort was the first white settlement on the upper Trinity River.

Bird’s Fort received provisions by supply wagon from Fort Inglish in Fannin County and from trading posts along the Red River. A spring near Calloway Lake provided drinking water.

But frontier life for civilians at Bird’s Fort was hard.

And if frontier life was hard for civilians, it was harder for soldiers. On Christmas Day 1841 snow covered the ground as Captain Webb, Solomon Silkwood, and Wade Hampton Rattan left the fort. Rattan, born in Illinois in 1811, was accompanied by his bulldog. By one account the three soldiers went out to search for an overdue supply wagon from the Red River settlements. Near today’s Carrollton the soldiers came upon a bear in a tree. Determined to kill the bear, as they were chopping down the tree, they were attacked by Native Americans who had been watching. The Native Americans fired three shots. Rattan was shot once and mortally wounded. The other two soldiers fled, leaving behind Rattan and his dog. Emergency response time was measured in days, not minutes, in that era. When Rattan’s body was recovered nine days later, Rattan’s dog was still with his dead master. Rattan’s body was returned to the fort and buried in a coffin made from the body of an old wagon. Bird’s Fort settler William H. Beeman, then fourteen years old, helped Rattan’s widow cut down cedar trees to make pickets with which to enclose the grave of her husband.

Rattan’s killing was reported in the Lexington Union of Mississippi. (James Webb Throckmorton would marry Rattan’s sister Annie.)

Rattan’s burial was probably the first in the graveyard of Bird’s Fort, located a few hundred yards northeast of the blockhouse. “This plot of graves,” the Star-Telegram wrote in 1934, “likely constitutes the first burying ground [of whites] in the county.”

Bird’s Fort settlers would bury more of their own in that first burying ground, but not for long.

In March 1842, after only six months, the soldiers abandoned Bird’s Fort. Why? You can take your choice of theories. Some historians say the fort was abandoned due to hardships of the winter and the threat of a Comanche attack. Other historians say the fort was abandoned because the enlistment terms of the volunteers expired in March 1842.

In 1902 William H. Beeman, by then an old man, in an interview said the fort was abandoned because of malarial conditions caused by a “stagnant lake,” surely meaning Calloway Lake.

And some say the fort was abandoned because of money: The Republic of Texas legislature had granted land six miles square, including the Bird’s Fort site, to Major Bird. But President Sam Houston vetoed the grant, instead giving settlement rights to Peters Colony. So, Major Bird dismissed his troops, abandoned the fort, and returned to Bowie County.

Left without the protection of soldiers, the Bird’s Fort settlers soon left. Some moved to the new settlement of Dallas, lured by John Neely Bryan, who had visited the fort to recruit. Among the Bird’s Fort settlers to follow Bryan was the family of young William H. Beeman. In fact, Bryan married Beeman’s sister Margaret.

Even though the fort had been abandoned, it still had some history to make.

In 1843 Colonel Jacob Snively, with the nod-and-wink consent of the Republic of Texas, set out to raid a Mexican caravan traveling through Texas on the Santa Fe Trail between Independence, Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Snively was, in a word, a privateer. The Snively raiders (among them Captain Shapley Prince Ross, father of Sul Ross) agreed to share their booty with the republic. But as the Snively raiders were on their way to wealth the United States accused the Snively expedition of being illegally on U.S. soil; the Republic of Texas accused the United States of illegally crossing onto Texas soil to order the raiders to disarm. Then dissent flared among the raiders themselves. The Snively expedition split into factions. Snively resigned his command but later was reelected. By the time Snively’s faction finally found a Mexican caravan to raid, his faction was too reduced in strength to take on the soldiers guarding the caravan. On August 5, 1843 at abandoned Bird’s Fort, the snakebitten Snively expedition disbanded.

In [an article from the July 26, 1843 edition of] the Telegraph and Texas Register, Coffee’s Station was a trading post on the Red River. The Register was the first newspaper with any permanence in the Republic of Texas. It was founded in San Felipe de Austin in 1835 but in 1837 moved to the new capital of Houston.

Abandoned Bird’s Fort made more history the next month.

In 1843 Sam Houston wanted to make peace with hostile tribes. He sought a treaty that would end hostilities, establish a line of demarcation between white settlers and tribes, and allow for white trading posts along that line. Houston dispatched Joseph C. Eldridge, the republic’s superintendent of Indian affairs, to visit hostile tribes and invite them to a treaty council at Bird’s Fort. Eldridge was accompanied by three Delaware chiefs who spoke English and several Native American dialects.

Houston himself traveled to Bird’s Fort in the summer of 1843 to hold a peace council with several tribes, including the Comanches, but some of the tribes feared that the council at the abandoned fort was a trap and shied away. So, Houston moved the council north to Grapevine Springs (today’s Grapevine). Although the Comanches were no-shows at Grapevine, this council laid the groundwork for a later council at Bird’s Fort.

Negotiating the treaty at Bird’s Fort in 1843 with Eldridge were two Indian commissioners of the republic: General George W. Terrell and General Edward H. Tarrant. Tarrant in 1841 had led the militia attack on Native Americans at the Battle of Village Creek just a few miles away.

The Treaty of Bird’s Fort was signed on September 29.

(By some accounts, Jesse Chisholm served as an interpreter at the Bird’s Fort treaty council. But one biographer says Chisholm was not present at the Bird’s Fort council.)

[An August 22, 1843 article in the Madisonian] about the Bird’s Fort council shows how slowly news traveled in those days. By the time a newspaper was carried by steamboat from Galveston to New Orleans to Washington City, its news was twenty-three days old. This clip also reminds us of the state of the world in 1843. The “Washington City” where the Madisonian was published was Washington, D.C. But in the sentence “The president has left Washington...” the “president” was Sam Houston, and “Washington” was Washington-on-the-Brazos, capital of the Republic of Texas.

Page 1 of the Treaty of Bird’s Fort:

“By the President of the Republic of Texas

Proclamation

To all and singular to whom these presents shall come, Greeting:

Whereas, a treaty of peace and friendship between the Republic of Texas and the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tah-woc-cany, Keechi, Caddo, Ana-dah-kah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee tribes of Indians, was concluded and signed at Bird’s Fort, on the Trinity River, on the twenty ninth day of September, in the year of Our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty three, by G.W. Terrell and E.H. Tarrant, Commissioners on the part of the Republic of Texas, and certain chiefs, Headmen and warriors of the tribes of Indians aforesaid, on the part of said Tribes; which treaty is, in the following words, to wit:

A Treaty of Peace and Friendship, Between the Republic of Texas, and the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tah-woc-cany, Keechi, Caddo, Ana-Dah-kah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee tribes of Indians, concluded and signed at [Bird's Fort]”

The last page of the treaty, ratified in 1844:

“Now, Therefore, be it known That I, Sam Houston, President of the Republic of Texas, having seen and considered said Treaty, do, in pursuance of the advice and consent of the Senate, as expressed by their resolution of the thirty first of January, one thousand eight hundred and forty four, accept, ratify and confirm the same, and every clause and article thereof.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Great Seal of the Republic to be affixed

Done at the town of Washington[-on-the-Brazos], this third day of February in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty four and of the Independence of the Republic the Eighth.

By the President

Sam Houston

Anson Jones

Secretary of State”

Article I’s declaration that both sides would “forever live in peace” didn’t come to pass, and after the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 Texas, by then part of the Union, was deemed to need more forts along the frontier of Texas to protect white settlers from Indians. The northernmost of those forts was Fort Worth.

Meanwhile, Major Bird had petitioned the republic for $653 ($15,000 today) for reimbursement for his expense in outfitting his soldiers and building short-lived Bird’s Fort. In 1844 William H. Bourland (who had fought at the Battle of Village Creek with brother James) of the Republic of Texas House of Representatives introduced a bill to reimburse Bird for his expenses. Sam Houston vetoed the reimbursement, citing the “present financial condition” of the republic.

In January 1845, just eleven months before the United States annexed Texas, the republic passed an act providing Major Bird with money from taxes collected in his Bowie County.

Major Jonathan Bird still had not collected all his money when he died in 1850.

The fort named for Major Jonathan Bird is long gone. But he was to have another namesake. In 1850, the year Bird died, newly created Tarrant County held an election to select a county seat. Per the provisions of the state legislature’s act of 1849, “the place receiving the highest number of votes shall be the place established as the county seat of said county of Tarrant, and shall be called Birdville.”

By the 1870s Calloway Lake and the site of the fort were owned by settlers whose name today is attached to the lake: brothers Richard and Joseph Calloway. A mile north of the lake is Calloway Cemetery, in use since 1874.

In the 1880s, some forty years after the short life of Bird’s Fort, Calloway Lake reinvented itself: It became a venue for organized hunting and fishing. In 1887 the Calloway Lake Hunting and Fishing Club, composed of Dallas men led by Captain W. H. Gaston (as in Gaston Avenue), bought the lake.

An 1895 map shows a clubhouse about where the fort had stood. By 1895 the club was operating as the Silver Lake Hunting and Fishing Club. [On the upper-left of the map can be seen] the surveys of the two Calloway brothers.

[Many articles in the Fort Worth Telegram praised] the amenities of the lake and the clubhouse.

Likewise, [a 1907 article] mentions the club’s natatorium (swimming pool).

Like Hust Lake to the west, Calloway Lake became popular for general recreation. People went to the lake to swim, picnic, sail.

By the twentieth century little evidence of Bird’s Fort remained. In 1926 J. J. Goodfellow, former surveyor of Tarrant County, wrote of the fort: “My first visit to the place was in 1866, at which time Colonel B. Rush Wallace was the owner of the property covering most of Calloway’s Lake and the ground upon which the blockhouse and graves are located. The remains of the [block]house were plainly visible. They stood at the northeast bank of the lake at a point where a country club later built a swimming pool and destroyed most of the signs of the trenches. From this blockhouse a path led in a northeasterly direction probably 250 to 300 yards through timber to the graves. The outer walls were in picket form, logs set on end, with deep ditches around the building.”

During the Texas centenary year of 1936 a granite historical marker was placed at the club’s swimming pool. The marker said the fort was located on the military road between the Red River and Austin. Other sources say the military road was farther east in Dallas County.

That granite marker eventually was damaged by vandals and relocated to nearby North Collins Street. The marker is gone now. Since 2003 [a newer] marker has been in nearby River Legacy Park.

By the 1950s the lake and fort site were being surrounded by gravel pits as excavation increased in the river bottom.

Despite the encroachment of excavation, the lake continued to be the site of organized hunting and fishing. In the 1960s the lake was leased to Arlington Sportsmen’s Club.

By the 1980s the lake and fort site were largely inaccessible and forgotten. The area became popular with illegal dumpers, stolen car strippers, and dirt bikers.

Today the site of a mid-nineteenth-century fort is surrounded by twenty-first-century housing. Calloway Lake is on land that is part of the Viridian “2,000-acre master plan” subdivision. Some of the gravel pits are now shallow lakes.

Viridian developer Robert Kembel said of the fort site in 2017: “This is the birthplace of North Texas. And we didn’t know that when we bought the property.” Kembel said he hopes to build a cultural center on the site to mark its history.

Today a visitor must ignore the bang and buzz of nail guns and power saws and the rumble of bulldozers and trucks to hear the sounds of Calloway Lake as it whispers its story of early Texas.